The UK government has set out an “action plan” for reaching its target of clean power by 2030, which it describes as “the most ambitious reforms to our energy system in generations”.

The plan outlines how the government hopes to “make Britain a clean energy superpower to cut bills, create jobs and deliver security with cheaper, zero-carbon electricity by 2030”.

This was one of five “missions” in the Labour manifesto, on which the government was elected with a landslide majority in July.

Following independent advice from the National Energy System Operator (NESO), the government is aiming for clean power to meet 100% of electricity demand by 2030, with at least 95% of electricity generation coming from low-carbon sources and no more than 5% from unabated gas.

The 136-page plan sees wind and solar – in particular offshore wind – becoming the backbone of the British electricity system. It says record amounts of new renewable capacity will need to be delivered, alongside reforms to the planning process and major grid enhancements.

While delivering all this would be a huge undertaking, the plan says it could unlock extra investments worth £40bn a year out to 2030, delivering “reindustrialisation”, jobs and lower bills.

Here, Carbon Brief explains the background to the clean power 2030 target, initial steps already taken by the government, the proposals in the new action plan and what comes next.

Where the clean power 2030 target comes from

The Labour party fought the 2024 UK election campaign on a manifesto pledging to “make Britain a clean energy superpower…with cheaper, zero-carbon electricity by 2030”.

This was an advance on the previous Conservative government’s 2021 pledge to “fully decarbonise” the power system by 2035.

Both parties had identified the need for clean power in order to help decarbonise the rest of the UK economy, as heat and transport are increasingly electrified with heat pumps and electric vehicles.

However, the Labour party has explicitly tied its clean power “mission” not just to the UK’s climate goals, but to energy security and bills in the wake of the global energy crisis, as well as jobs.

In a press statement launching the report, secretary of state for energy and climate change Ed Miliband says:

“A new era of clean electricity for our country offers a positive vision of Britain’s future with energy security, lower bills, good jobs and climate action. This can only happen with big, bold change and that is why the government is embarking on the most ambitious reforms to our energy system in generations. ”

Just after taking office at the start of July 2024, Miliband reiterated his commitment to the clean power 2030 target when setting out his priorities for government.

He then appointed Chris Stark, the former chief executive of the Climate Change Committee, to head up a new “mission control” function within government, as well as informally asking NESO for independent advice on how to reach the clean power 2030 target.

(NESO was created as part of the Energy Act 2023, having already been hived off from National Grid. It was officially launched on 1 October 2024 as a new independent organisation responsible for planning the entire energy system in Britain, including operating the electricity network and offering “expert advice to the energy sector’s decision makers”.)

Speaking to UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC) director Prof Rob Gross on the Talking Energy podcast, NESO chief economist Mike Thompson said the body had begun working on its advice to government in July 2024, soon after the election result became clear.

The government had then formally requested NESO’s guidance in an August 2024 letter, which asked for “practical advice on achieving clean power by 2030”.

It asked for different pathways to reach this goal, as well as key requirements for electricity grids, high-level analysis of costs and benefits, and suggested actions to get on track.

The NESO advice, published on 5 November 2024, said the 2030 target was “achievable…without increasing costs” and that it would insulate the UK from “volatile international gas prices”.

A key element of the NESO advice was to offer a working definition of clean power by 2030.

It adopted a definition with two parts. It said clean power should cover 100% of electricity demand by 2030, in a year with average weather conditions. In addition, it said at least 95% of the electricity generated within the country’s borders should come from low-carbon sources, with up to 5% coming from unabated gas. This means the country would become a net electricity exporter.

(The national electricity grid – and the clean power 2030 target – technically only covers the island of Great Britain, whereas Northern Ireland is part of the separate all-Ireland network.)

Thompson explained on the Talking Energy podcast:

“We think that there should be enough clean power to cover all of GB demand over the year…But of course, a lot of that generation is coming from wind power, from solar, and you can’t control when it is outputting…So we adopted this definition that actually you cover all of demand [with clean power], but you would also allow up to no more than 5% of generation to come from unabated gas.”

The government formally adopted the NESO definition of clean power when prime minister Keir Starmer announced his milestones for delivering a “decade of national renewal”.

This definition, for clean power to meet 100% of demand in 2030 but only 95% of generation, was widely reported as a “watering down” of Labour’s manifesto pledge. A spokesperson for the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero said this was “categorically untrue”.

Labour’s manifesto had not defined its clean power by 2030 target and had made clear reference to a “strategic reserve of gas power”.

An earlier Labour policy document had said that the country would “run on 100% clean…power”, which is consistent with the government’s target for clean power to meet 100% of demand.

Back to top

What clean power 2030 will look like

The government’s action plan accepts the NESO advice as its starting point.

While NESO offered two different pathways to clean power in 2030, they share many of the same features, with wind and solar making up the largest share of electricity in both cases.

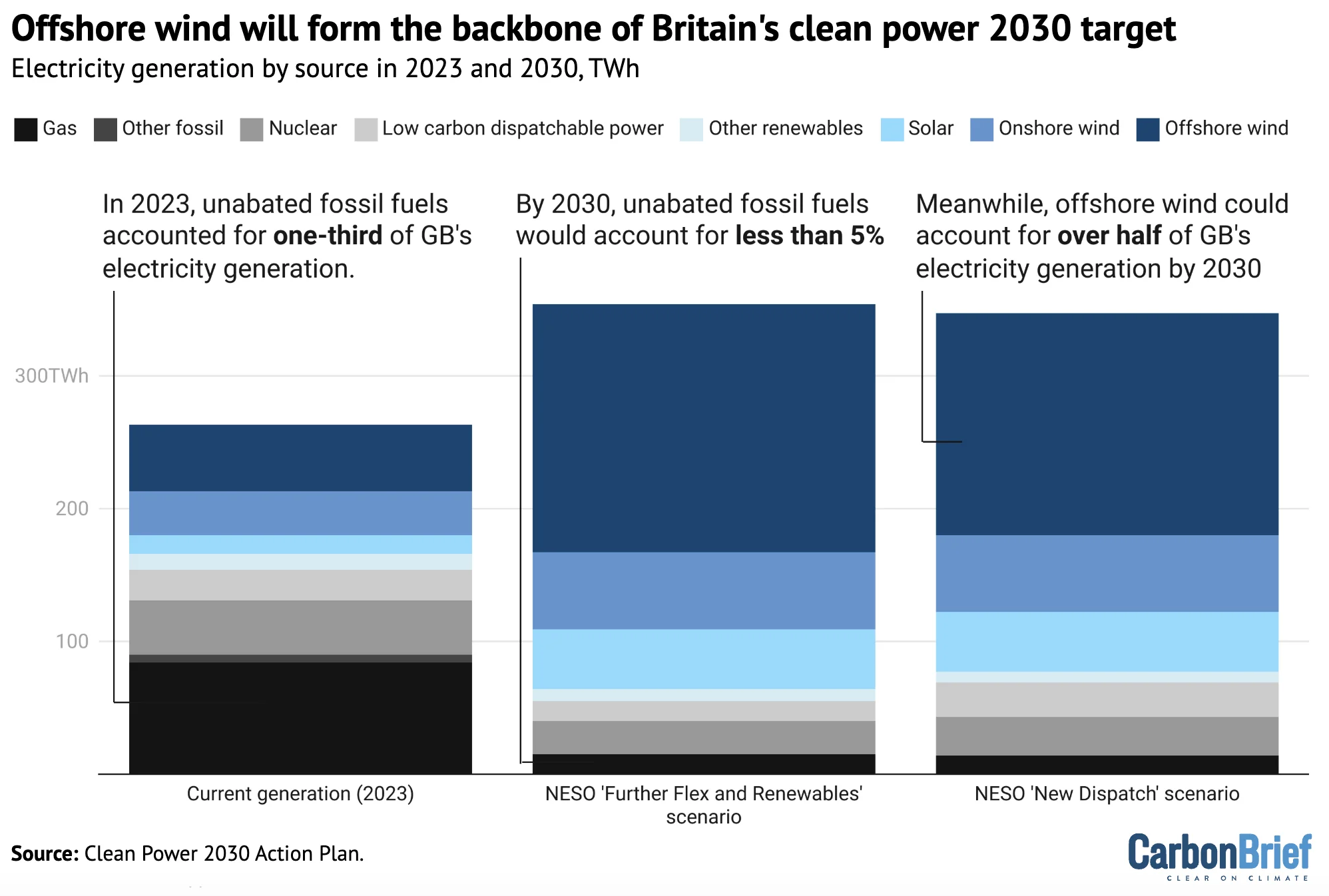

In 2023, fossil fuels made up a third of electricity generation in the country, with wind and solar making up another third, and the remainder coming from nuclear, biomass and imports.

By 2030, if the clean power target is met, unabated fossil fuels would make up less than 5% of generation, with wind and solar making up around 80% of the mix, as shown in the figure below.

Offshore wind would form the backbone of the GB electricity mix in 2030, meeting around half of demand under either the NESO “new dispatch” scenario or under “further flex and renewables”.

The difference between the two NESO pathways lies in the way that they manage gaps in the output of variable wind and solar power.

The “new dispatch” pathway relies more on low-carbon “dispatchable” power, meaning capacity that can be turned on and off at will. This includes gas-fired power stations fitted with carbon capture and storage (CCS), or turbines that burn low-carbon hydrogen fuel.

The “further flex and renewables” pathway relies on larger amounts of wind and solar capacity, coupled with a more flexible grid and higher levels of battery or long-duration energy storage.

The government’s action plan targets a range of clean power capacity by 2030 that would leave the door open to pursuing either of these scenarios, shown in the table below.

Crucially, the plan relies on keeping almost all of the country’s existing gas-fired power stations open for the rest of the decade, to help bridge those gaps in wind and solar output, until alternative low-carbon sources of flexibility become more widely available.

Thompson told the Talking Energy podcast:

“You keep something like a fleet around the size of the current gas fleet open [in 2030], but it would operate much, much less.”

While the existing gas fleet remains in place, the government will need to rapidly expand the amount of clean power capacity available to meet the 2030 target.

The action plan says the long timelines for new offshore wind projects mean there will only be time to bring forward schemes that are already or at least part-way through the planning process.

It also means that the next two “contracts for difference” (CfD) auctions, due to be held in 2025 and 2026, will need to secure the bulk of the offshore wind capacity required for 2030.

The UK currently has 15 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind capacity, with another 16GW under construction or firmly committed. To meet the level required for clean power by 2030, the plan says that this would need to expand by at least another 12GW by 2030.

Similarly, at least an additional 8GW of onshore wind and 22GW of solar would be needed.

The Financial Times quoted a “government figure” saying that next year’s auction will need to be “huge” and the biggest ever for the country:

“When you think about the long lead times for a project like an offshore wind farm it makes sense to get going with the CfDs now and throw the book at this with a huge auction round as soon as possible, probably next year…It would be the biggest we’ve seen so far.”

In addition to building that new capacity, the plan relies on significantly enhancing the electricity transmission grid that sends power around the country, reforming the planning system so that new infrastructure can be built and ensuring the supply chains and workers are in place to deliver.

In a foreword to the action plan, Stark says the wider economic benefits of meeting the target are a “prize” worth around £40bn in investment every year until 2030.

The plan describes this as “once-in-a-generation levels of energy investment” that will “spread…the economic benefits of clean energy investment throughout the UK”. It adds:

“These investments will protect electricity consumers from volatile gas prices and be the foundation of a UK energy system that can bring down consumer bills for good. Every choice we make will be scrutinised to maximise the impact it can have in reducing consumer bills.”

The plan says that the clean power plan will “provide…the foundation to build an energy system that can bring down bills for households and businesses for good.” It adds:

“In their advice, NESO set out their analysis of potential impacts of delivering clean power on electricity costs in 2030. This indicated it could be delivered with similar costs to today, with scope for lower electricity costs and bills by 2030 as wider changes are taken into account.”

Ahead of the general election, Labour had promised that its clean power plan would cut energy bills by up to £300. The opposition Conservatives have disputed this.

On the question of how it would be possible to reduce bills while building large amounts of new infrastructure, UKERC’s Gross explained on the Talking Energy podcast that instead of spending large amounts on imported fossil fuels that are burned to generate electricity, billpayers would be investing in new clean power capacity, which would be paid back over many years.

Back to top

How the government plans to reach clean power 2030

Achieving the clean power 2030 target would be a major undertaking. The government’s action plan sets out its approach to delivering this across a series of key areas.

Actions include reforming and expanding the government’s auctions for new clean power capacity, significantly expanding the country’s electricity grid and speeding up the process of connecting new projects, changing the planning system so that all this new infrastructure can be consented and built, and ensuring a supply chain with skilled workers is in place to deliver it.

Grid enhancement

The action plan outlines steps to expand and improve the electricity grid, saying that a failure to strengthen it “risks holding back our energy security, economic growth and other important infrastructure with lengthy delays”.

For example, it notes that, if no action is taken to address the annual “constraint costs” caused when networks are unable to carry all of the clean power being generated to where it is needed, then those costs are projected to increase from the “already high level” of £2bn per year in 2022 to around £8bn per year (or £80 per household) by the late 2020s.

An “unprecedented expansion” is therefore needed to deliver decarbonisation, energy security and affordability, with around twice as much new transmission infrastructure needed by 2030 as has been delivered in the past decade.

To enable this, the plan sets out several key actions, including reforming the connections process, reforming regulations, improving planning and consenting, and engaging with communities.

In the last five years, the grid “connection queue” of projects waiting to hook up to the electricity network has grown tenfold. Many of the projects within the queue are speculative or do not necessarily have the funding or planning permissions to progress, the action plan notes.

It says this means that fundamental reform is needed. Work has already begun on this. For example, in November the government, together with energy regulator Ofgem, outlined a series of changes in a joint letter that would fast-track renewable, clean power and storage projects.

The action plan includes further reform to the current “first come, first served” process for the queue. The government says it will go beyond previous plans to simply remove slow or stalled projects from the queue and prioritise readiness alone.

It will now also consider technological and locational factors, remove unviable projects, re-order the queue and accelerate connection timescales, the action plan states.

In a foreword to the plan, Miliband says:

“Ultimately, we need to move fast and build things to deliver the once-in-a-generation upgrade of our energy infrastructure Britain needs.”

Following consultations with Ofgem, NESO and network companies, there are now detailed methodologies for filtering the queue and prioritising connections for strategically important plans.

These changes will take into account recommendations from both electricity networks commissioner Nick Winser’s report in 2023 – which set out recommendations to halve the connection times of projects – and NESO’s Clean Power 2030 advice, which confirmed the need for 80 new transmission grid projects to be built, if the target is to be achieved.

Additionally, the action plan notes that, wherever renewable projects can be connected to the lower-voltage local distribution systems, instead of the high-voltage national transmission grid – known as the motorways of the electricity network – this should be encouraged.

(Projects that have secured a CfD or “capacity market” contract, “nationally significant” projects and others that are considered well advanced will be included in the reformed connections queue, according to the plan.)

Beyond the connections queue, the action plan sets out regulatory reforms to support clean power by 2030. This includes amending the Strategy and Policy Statement, wherein the government’s strategic priorities for energy policy are outlined, to ensure that 2030 clean power and decarbonisation more broadly are weighted in decision making.

The government will also work with Ofgem to explore the appropriateness of tightening incentives and penalties for network operators, for the delivery of strategically important infrastructure.

To accelerate the build out of both transmission and distribution networks required for the 2030 target, planning system changes will be required. (See: Planning reforms.)

Currently, it can take between two to four years to gain land rights in England and Wales, which can “lead to unnecessary delays”, the action plan notes.

To address these processes, the action plan says that planning consent exemptions will be expanded to include low-voltage connections and upgrades.

There are also further opportunities to provide flexibilities on the consenting of electricity substations, it adds.

The final core part of action on the grid, outlined in the plan, focuses on community engagement, as “this government believes that it is a vital principle that communities that host clean energy infrastructure should benefit from it”.

This will include publishing voluntary guidance to increase the amount and consistency of community benefit funds from transmissions networks. There will also be support for the launch of a public communications campaign around grid expansion, the plan says.

Back to top

Planning reforms

Since the election in July, the Labour government has taken several steps to help transition the electricity system towards net-zero.

This includes lifting the de-facto ban on onshore wind in England, which had been in place since 2015, within weeks of taking office.

Labour also approved three large solar farms in its first few weeks in government. In total, these sites – Gate Burton in Lincolnshire, Mallard Pass in Lincolnshire and Sunnica in Suffolk and Cambridgeshire – have a capacity of over 1.3GW.

Given their size, all three solar sites are considered nationally significant infrastructure projects (NSIPs), and as such require a development consent order from the energy secretary, as opposed to planning permission from the local planning authority.

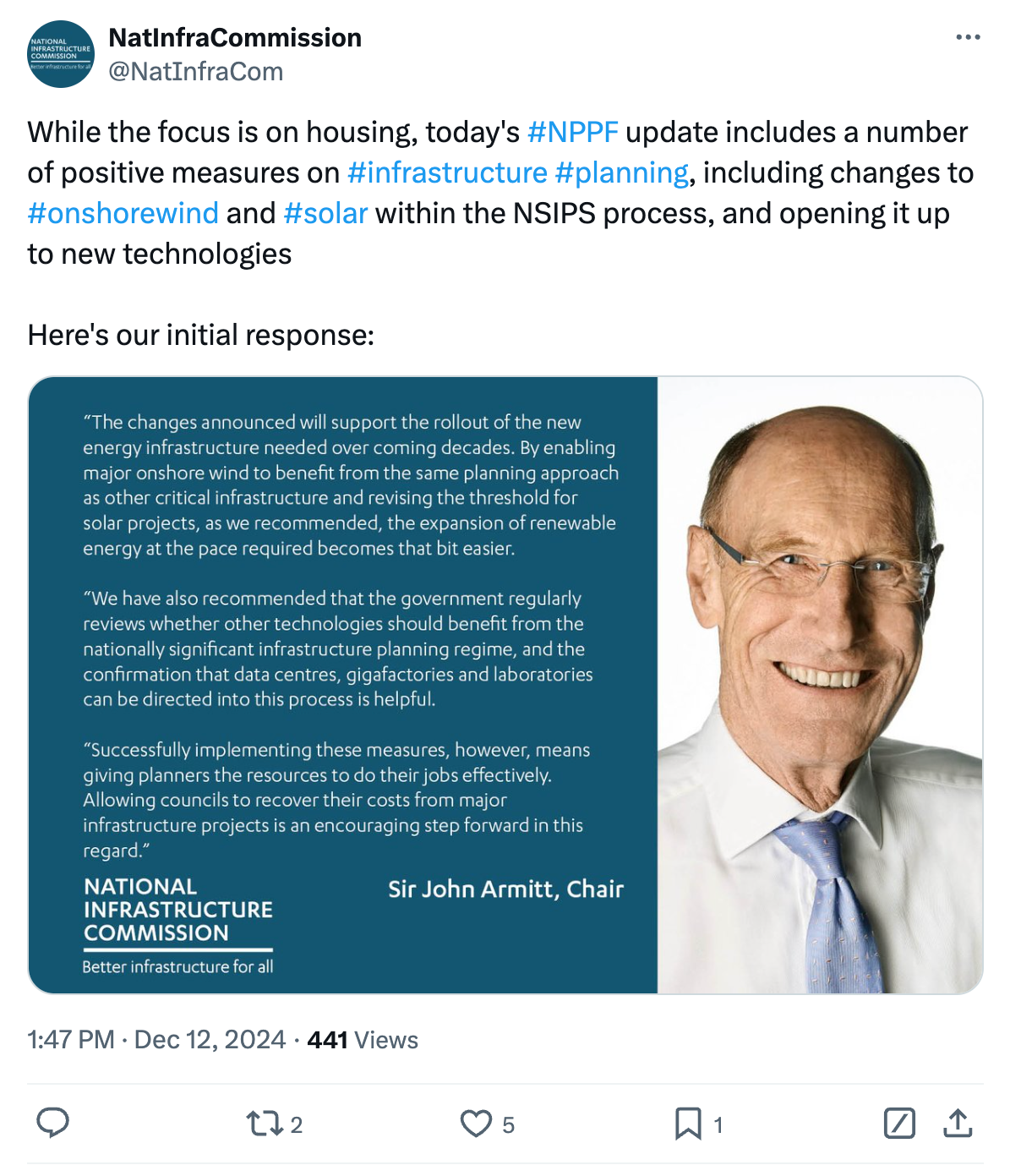

One day before the action plan was released, the government published its response to a consultation on proposed changes to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF).

This includes plans to bring onshore wind back under the NSIP regime, in line with other types of major infrastructure. It also intends to raise the threshold above which onshore wind and solar projects will need central government NSIP consent to 100 megawatts (MW).

The government is planning to introduce legislation in the spring of 2025 to bring in these changes.

The action plan builds on these changes in an effort to improve the planning process.

It states that the planning system is “not working at the pace required” to meet the 2030 target and that this “urgent need for change” necessitates “a wide-ranging reform programme”.

To enable clean power by 2030, most new transmission grid and offshore wind projects will need all relevant planning permissions to be in place by 2026, the report notes.

While onshore wind, solar and battery energy storage projects have shorter construction timelines, they will still likely need to have received planning consent by 2028.

The report states that the government has identified pathways for delivery for “firm” generation – such as nuclear – as well as for sources of low-carbon flexibility, but does not give a date by which they must be consented.

Other changes outlined in the report include equipping organisations such as the Planning Inspectorate, statutory consultees such as the Environment Agency, local planning authorities and government consenting teams, with the “tools they need” to make decisions faster.

The report highlights that, in 2023-24, more than 60% of delayed responses to planning applications from the Environment Agency were due to resourcing constraints, and for nature regulator Natural England it was more than 80%.

It promises changes including boosting local planning capacity, expanding cost-recovery mechanisms – which see developers pay for the work needed to give them planning consent – and longer-term reforms. In particular, the changes will allow them to “better flex and prioritise their resources” so that “mission-critical projects” can be processed faster, it says.

The action plan includes updating “national policy statements” (NPSs) for energy and planning policy guidance in 2025, along with the changes to the NPPF already announced.

A programme of legislative reform will be undertaken by the government, including through the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, which will be brought forward next year. This will include NPSs being updated every five years, through a “quicker and easier process”.

Further reforms to the NSIP planning system in England and Wales will be undertaken, as well as changes to infrastructure consenting in Scotland.

(There is executive devolution in Scotland with regards to the infrastructure planning system, however under the Electricity Act, reserved to Westminster, the UK government will be able to bring in changes to deliver a “streamlined and efficient framework”, the plan says.)

The report highlights the importance of a coordinated approach to planning and notes that, to support this, NESO will deliver a “strategic spatial energy plan” in 2026, setting out a long-term approach to planning to deliver net-zero by 2050.

Under the NSIP process, the government will undertake a review of the lawfulness of challenges to development consent for major infrastructure. While judicial review is a “constitutionally important mechanism”, the action plan notes, most are unsuccessful and can take many years, significantly delaying new infrastructure and increasing costs to consumers.

As such, the plan includes a commitment to reform the judicial review process for NSIPs, following the Banner report on why such legal challenges arise.

Additional actions announced within the plan include changes to ensure communities can directly benefit from the clean energy infrastructure they host.

It notes that locally-consented energy infrastructure can take up to 12 months to receive a decision on a planning application, despite a four-month limit on projects that require an environmental impact assessment

Finally, the plan says that, by delivering a “marine recovery fund” for offshore wind, as well as using development to fund nature recovery, the government will look to use the action plan to protect nature and ensure that it is embedded in the transition to clean power by 2030.

Back to top

Renewable energy auctions

The action plan announces further changes to the CfD support scheme for new renewable energy.

This follows action by the current government earlier in the year to bolster the sixth CfD auction, including increasing its budget by over 50% from the level set in March under the previous Conservative government to £1.56bn.

(The previous fifth auction, held in 2023, had not secured any new offshore wind.)

This year’s sixth auction contracted more than 130 new wind, solar and tidal energy projects, amounting to 9.6GW of capacity. Still, some cautioned at the time that a “big step-up” would still be required if the power sector is to be decarbonised by the end of the decade.

The government is introducing a number of changes to the CfDs ahead of the seventh auction, due to be held in 2025. This includes allowing onshore wind farms that are “repowering” – meaning replacing old turbines as they retire with newer models – an extension to the “phasing” process for floating offshore wind and streamlining the appeals process to take place ahead of the auction.

There is currently around 31GW of offshore wind built, under construction or contracted. However, this needs to rise to 43-50GW in 2030. (See: What clean power 2030 will look like).

The government will therefore aim to secure at least 12GW of new projects over the next two allocation rounds. To enable this, the action plan sets out further reform to the CfD process.

Changes will include a relaxation of the CfD eligibility criteria for fixed-bottom offshore wind projects to allow projects to bid even if they have not obtained full planning consent.

To avoid a repeat of the fifth auction, there will also be changes to the information the secretary of state uses to inform the final budget for fixed-bottom offshore wind.

There will also be a review of auction parameters, following “industry concerns” around the way the notional “budget” of each round is calculated.

(The “budget” for each auction round is an artificial construct, set by the government and designed to limit the impact of CfDs on consumer bills. Any support for CfD projects is paid for by billpayers rather than from government budgets. Moreover, a larger “budget” may not translate into higher bills, because CfD projects also push down wholesale electricity prices.)

Specifically, the government will look at the “reference price” against which each new CfD scheme is valued. Recent auction rounds have used very low reference prices, which inflate the notional budget impact of new projects, even if they are likely to lower consumer costs.

The government is also considering changes to the CfD contract terms to give longer market security, once the contracts are awarded. This could see the length of the contracts increased from the current 15-year standard term.

Consultations will take place in early 2025, ahead of the seventh allocation round, with a view to implementing them in the summer of 2025.

Beyond the CfD reforms, the action plan includes a number of commitments to improve renewable energy project delivery. These include facilitating greater coordination between wind turbines, civil aviation and defence infrastructure.

Further detail on Great British Energy’s (GBE) project development is included, including promises that the state-owned energy company – a core part of the Labour manifesto – will align its projects on private land with NESOs location suggestions, and develop further projects on public land.

The action plan states that GBE will provide support to deliver the Local Power Plan, to put “local authorities and communities at the heart of restructuring our energy economy”. Additional work will be done to support the deployment of rooftop solar, assess the potential of solar “canopies” on outdoor carparks and support programmes such as the Warm Homes Local Grant.

First introduced in 2002, the UK-wide renewables obligation (RO) scheme currently supports around 30% of the UK’s electricity supply. From 2027, it will start to come to an end, with around 9GW of capacity reaching the end of the subsidy by December 2030.

The action plan commits the government to conduct further analysis to inform the possible policy options needed to manage the risk that RO-supported projects might stop operating.

For the work being undertaken on renewables and nuclear, the action plan includes a list of key upcoming milestones, including:

- Spring 2025: Solar Roadmap and the Onshore Wind Industry Taskforce report.

- Early 2025: Consultation on relevant reforms to the CfD scheme.

- “In due course”: Consultation response on the Future Homes and Buildings Standards.

- After the spending review: Further details on the Warm Homes Plan.

- In 2025: A call for evidence on the potential to drive solar canopies on carparks.

- “In due course”: Consultation response on transitional support for large-scale biomass.

Back to top

Flexibility and ‘dispatchable’ clean power

Beyond renewables, the plan includes a number of actions to reform the electricity market to support energy security, through flexibility and “dispatchable” power.

As with the other core areas, the government has taken a number of actions in its first six months to support this, including signing the contracts for the first gas CCS project in the UK.

French utility firm EDF has also announced plans to keep four existing nuclear power stations open for longer, meaning 4.6GW of nuclear capacity will remain on the grid in 2030.

The action plan includes support for investor certainty through wholesale electricity market reforms, reforming the capacity market and accelerating reforms to the balancing markets through which supply and demand are matched in real time, which it says will help unlock consumer-led flexibility. It notes:

“While the state must play a role as system architect, markets are, and will remain, central to the development, delivery, and operation of the power system.”

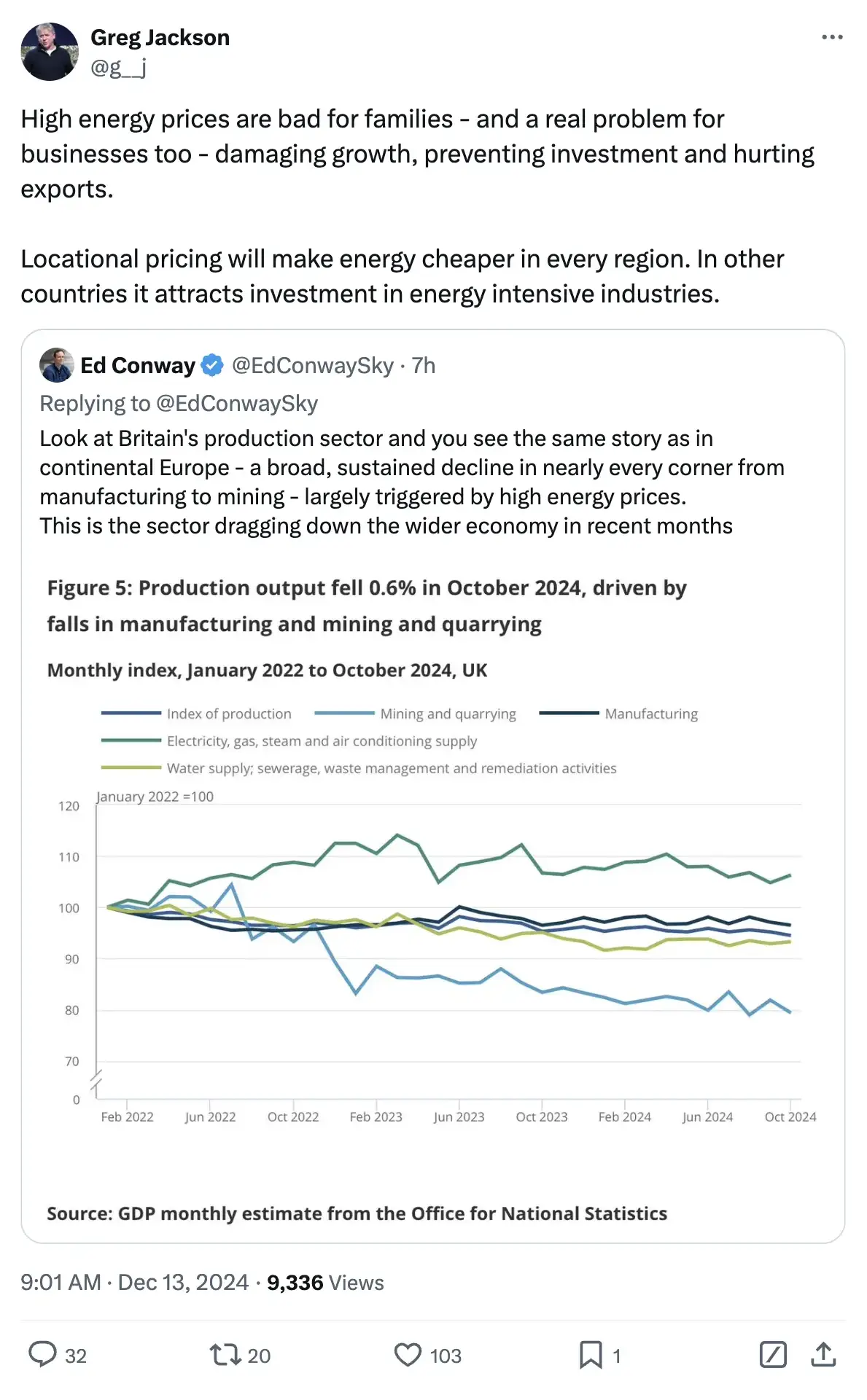

The action plan promises to set a clear “direction of travel” for wholesale market reform. As part of this, it is continuing to conduct further analysis as part of the long-running review of electricity market arrangements (REMA), which began in 2022 under the previous government. The action plan says that its work so far has made clear that “no change” is not an option.

The government says it will conclude the REMA process by “around mid-2025”, including whether to bring in “zonal pricing” or whether electricity prices will continue to be set at national level.

Currently, Britain uses a national pricing system whereby generators are paid the same regardless of where they are. Zonal pricing is a form of “locational pricing” that would see the country divided into zones, in an effort to reduce grid constraints and energy costs.

In order to avoid any changes affecting the investment needed in new clean power capacity, the government pledges to “align” the process with the next CfD auction. It also flags the potential for “transitional or legacy arrangements” that could protect existing investments from future changes:

“We plan, therefore, to announce the final decisions on REMA and the timetable for their implementation, particularly in relation to wholesale market reform and any transitional or legacy arrangements, before the AR7 auctions open, giving investors clarity for prospective bids.”

Other actions include NESO promising an electricity system operability strategy for 2030, improved forecasting of medium to long-term grid operability needs and improved emissions reporting from NESO across all electricity markets.

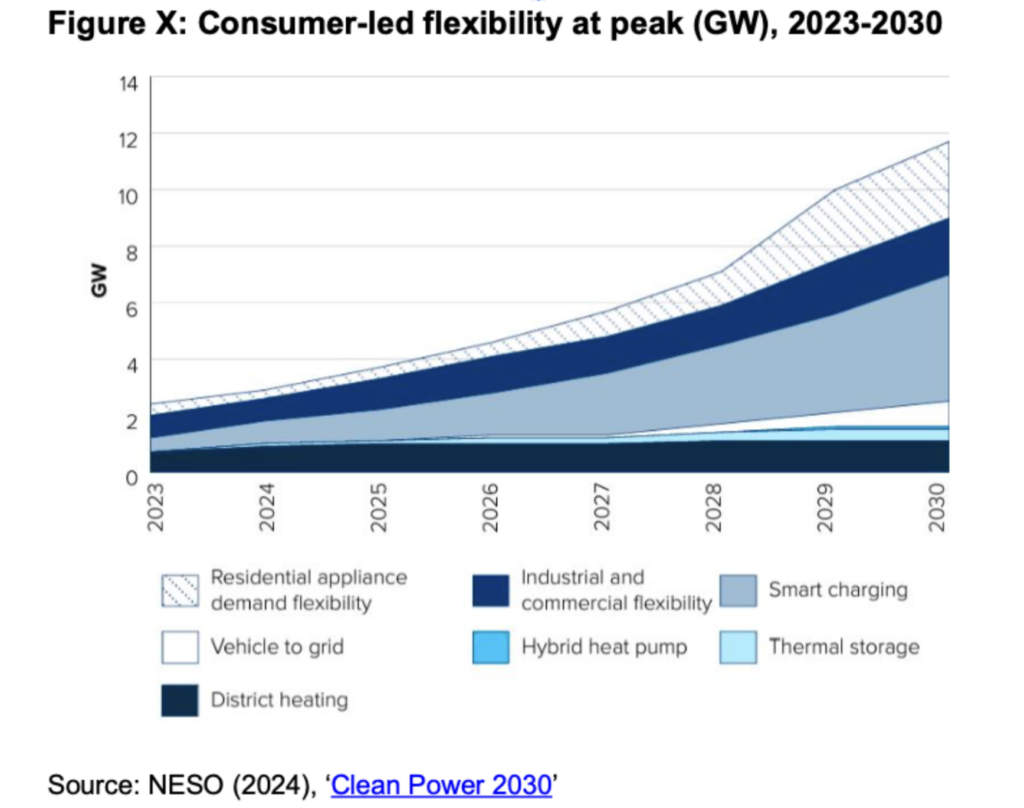

To support greater flexibility in the electricity system, the government plans to publish a “low carbon flexibility roadmap” in 2025. This will consolidate existing and future actions to drive short and long-duration flexibility.

Currently, there is 4.5GW of battery storage in Great Britain, the majority of which is grid-scale assets. By 2030, 23-27GW of battery storage is expected to be needed to meet the demands of a clean power system.

The action plan includes specific measures to overcome “hurdles” in the rollout of battery storage, such as working with Ofgem to ease network connections. (See: Grid enhancement.)

It says it will bring in incremental market reforms to provide batteries and consumer-led flexibility with access to relevant markets. This could include, for example, households shifting demand from electric vehicle charging at home, to use abundant renewable generation late at night instead of during peak hours when the grid is strained.

To support this, the action plan suggests enhancing rewards for consumers who choose to participate in flexibility, as well as the need for changes to market access for flexibility providers and support for the rollout of smart appliances.

Finally, work will be undertaken to enable portfolios of projects and activities to deliver consumer-led flexibility. Among other things, this builds on the rollout of the demand flexibility mechanism, whereby households are paid to reduce energy consumption during tight periods.

The action plan identifies the need for further long-duration flexibility technologies and announces support for the development of a hydrogen power business model to derisk investment and speed up the rate of deployment.

Additionally, Ofgem will introduce a “cap and floor scheme” to support investment in long-duration electricity storage. It says it is aiming to publish an open letter on specific aspects of the scheme soon, and in the first quarter of next year, DESNZ and Ofgem will publish the technical decisions undertaken to provide clarity on any outstanding areas of its design.

NESO has agreed to provide further advice as to the range of technologies needed. The scheme is expected to open to applications in the second quarter of next year.

Back to top

Sharelines from this story

Discussion about this post