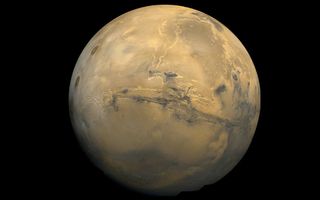

Mars is a planet of vast contrasts — huge volcanoes, deep canyons, and craters that may or may not host running water. It will be an amazing location for future tourists to explore, once we put the first Red Planet colonies into motion. The landing sites for these future missions will likely need to be flat plains for safety and practical reasons, but perhaps they could land within a few days’ drive of some more interesting geology. Here are some locations that future Martians could visit.

Olympus Mons is the most extreme volcano in the solar system. Located in the Tharsis volcanic region, it’s about the same size as the state of Arizona, according to NASA. Its height of 16 miles (25 kilometers) makes it nearly three times the height of Earth’s Mount Everest, which is about 5.5 miles (8.9 km) high.

Olympus Mons is a gigantic shield volcano, which was formed after lava slowly crawled down its slopes. This means that the mountain is probably easy for future explorers to climb, as its average slope is only 5 percent. At its summit is a spectacular depression some 53 miles (85 km) wide, formed by magma chambers that lost lava (likely during an eruption) and collapsed.

Tharsis volcanoes

While you’re climbing around Olympus Mons, it’s worth sticking around to look at some of the other volcanoes in the Tharsis region. Tharsis hosts 12 gigantic volcanoes in a zone roughly 2500 miles (4000 km) wide, according to NASA. Like Olympus Mons, these volcanoes tend to be much larger than those on Earth, presumably because Mars has a weaker gravitational pull that allows the volcanoes to grow taller. These volcanoes may have erupted for as long as two billion years, or half of the history of Mars.

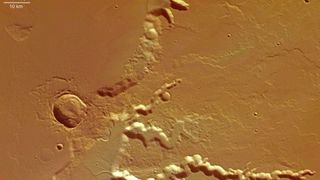

The picture here shows the eastern Tharsis region, as imaged by Viking 1 in 1980. At left, from top to bottom, you can see three shield volcanoes that are roughly 16 miles (25 km) high: Ascraeus Mons, Pavonis Mons, and Arsia Mons. At upper right is another shield volcano called Tharsis Tholus.

Valles Marineris

Mars not only hosts the largest volcano of the solar system, but also the largest canyon. Valles Marineris is roughly 1850 miles (3000 km) long, according to NASA. That’s about four times longer than the Grand Canyon, which has a length of about 500 miles (800 km).

Researchers aren’t sure how Valles Marineris came to be, but there are several theories about its formation. Many scientists suggest that when the Tharsis region was formed, it contributed to the growth of Valles Marineris. Lava moving through the volcanic region pushed the crust upward, which broke the crust into fractures in other regions. Over time, these fractures grew into Valles Marineris.

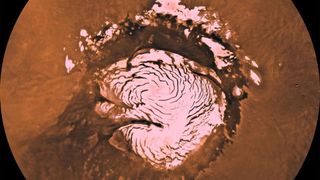

The North and South Poles

Mars has two icy regions at its poles, with slightly different compositions; the north pole (pictured) was studied up close by the Phoenix lander in 2008, while our south pole observations come from orbiters. During the winter, according to NASA, temperatures near both the north and south poles are so frigid that carbon dioxide condenses out of the atmosphere into ice, on the surface.

The process reverses in the summer, when the carbon dioxide sublimates back into the atmosphere. The carbon dioxide completely disappears in the northern hemisphere, leaving behind a water ice cap. But some of the carbon dioxide ice remains in the southern atmosphere. All of this ice movement has vast effects on the Martian climate, producing winds and other effects.

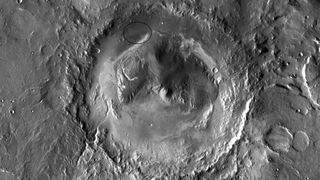

Gale Crater and Mount Sharp (Aeolis Mons)

Made famous by the landing of the Curiosity rover in 2012, Gale Crater is host to extensive evidence of past water. Curiosity stumbled upon a streambed within weeks of landing, and found more extensive evidence of water throughout its journey along the crater floor. Curiosity is now summiting a nearby volcano called Mount Sharp (Aeolis Mons) and looking at the geological features in each of its strata.

One of Curiosity’s more exciting finds was discovering complex organic molecules in the region, on multiple occasions. Results from 2018 announced these organics were discovered inside of 3.5-billion-year-old rocks. Simultaneous to the organics results, researchers announced the rover also found methane concentrations in the atmosphere change over the seasons. Methane is an element that can be produced by microbes, as well as geological phenomena, so it’s unclear if that’s a sign of life.

Medusae Fossae

Medusae Fossae is one of the weirdest locations on Mars, with some people even speculating that it holds evidence of some sort of a UFO crash. The more likely explanation is it is a huge volcanic deposit, some one-fifth of the size of the United States. Over time, winds sculpted the rocks into some beautiful formations.

But researchers will need more study to learn how these volcanoes formed Medusae Fossae. A 2018 study suggested that the formation may have formed from immensely huge volcanic eruptions taking place hundreds of times over 500 million years. These eruptions would have warmed the Red Planet’s climate as greenhouse gases from the volcanoes drifted into the atmosphere.

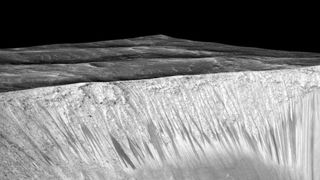

Recurring Slope Lineae in Hale Crater

Mars is host to strange features called recurring slope lineae, which tend to form on the sides of steep craters during warm weather. It’s hard to figure out what these RSL are, though. Pictures shown here from Hale Crater (as well as other locations) show spots where spectroscopy picked up signs of hydration. In 2015, NASA initially announced that the hydrated salts must be signs of running water on the surface, but later research said the RSL could be formed from atmospheric water or dry flows of sand.In reality, we may have to get up close to these RSL to see what their true nature is. But there’s a difficulty — if the RSL indeed host alien microbes, we wouldn’t want to get too close in case of contamination. While NASA figures out how to investigate under its planetary protection protocols, future human explorers may have to admire these mysterious features from afar, using binoculars.

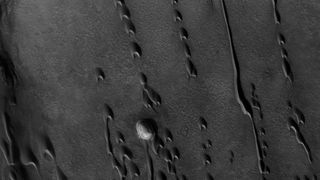

‘Ghost Dunes’ in Noctis Labyrinthus and Hellas basin

Mars is a planet mostly shaped by wind these days, since the water evaporated as its atmosphere thinned. But we can see extensive evidence of past water, such as regions of “ghost dunes” found in Noctis Labyrinthus and Hellas basin. Researchers say these regions used to hold dunes that were tens of meters tall. Later, the dunes were flooded by lava or water, which preserved their bases while the tops eroded away.

Old dunes such as these show how winds used to flow on ancient Mars, which in turn gives climatologists some hints as to the ancient environment of the Red Planet. In an even more exciting twist, there could be microbes hiding in the sheltered areas of these dunes, safe from the radiation and wind that would otherwise sweep them away.

Originally posted on Space.com.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/31/3431771d-41e2-4f97-aed2-c5f1df5295da/gettyimages-1441066266_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post