OTTAWA — COVID-19 has thrown Canada’s already struggling health-care system into chaos, forcing impossible choices when it comes to how to rebuild once the pandemic has ebbed.

Hospitals were forced to cancel elective surgeries during pandemic peaks, making already protracted lists now so long physicians are concerned patients will die while they wait.

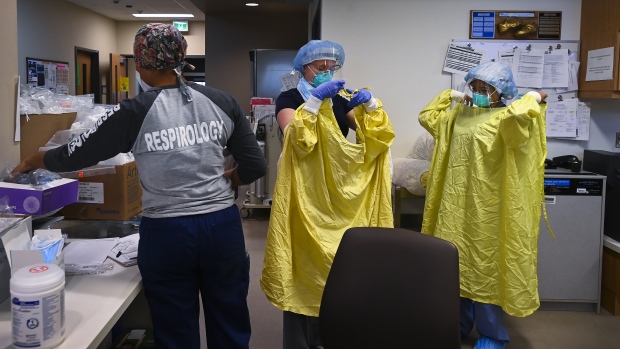

Meanwhile nurses are burnt out from the last year and a half of operating in a pandemic to the point that they’re exiting the industry in droves, leaving hospitals and health systems with the distasteful choice to either plow through surgeries or shore up nursing staff.

Almost 560,000 fewer surgeries were performed over the first 16 months of the pandemic compared to 2019, according to the latest figures from the Canadian Institute for Health Information. And the cost of addressing those backlogs is expected to run into the billions.

But a Harvard professor from the former Soviet Union with an affinity for Canada claims he has the solution, and it’s already working in some Ontario hospitals.

In extremely oversimplified terms: make surgeons work weekends.

“It means that you reduce the waiting time for surgery in Canada,” said Eugene Litvak, president of the non-profit Institute for Health Care Optimization in Massachusetts.

“It means that more patients will get treated.”

It all comes down to how hospitals admit patients, he said.

Litvak said a graph tracking patient flows would resemble an erratic electrocardiogram, with steep peaks and valleys, signalling a potential health disaster.

He said most people with common sense would assume the inconsistent ebbs and flows in hospital occupancy are caused by unpredictable health emergencies.

“But here is the secret: that the common sense and the health-care delivery are not compatible,” said Litvak.

In fact, he said, most of the variability is caused by scheduled procedures.

“It is easier for me to predict when somebody will break a leg and come to the hospital than when scheduled surgery will take place. And that’s the core of the problem,” he said.

Litvak says surgeons typically prefer to schedule their procedures early in the week to avoid getting called in to check on patients over the weekend.

That means surgical patients take up more beds earlier in the week, leaving people in the emergency room with long waits to get admitted. Hospitals are jammed by mid-week and nurses are overloaded with patients, he explained.

Litvak says the most common approach in Canada involves forming taskforces or issuing recommendations, a tactic he says addresses only the symptoms rather than the cause of escalating backlogs.

A more concrete solution, he suggests, should involve flattening the troubling peaks and valleys by putting equal demand on the system every day of the week when it comes to scheduled surgeries.

The idea isn’t a new one. Dr. Harvey Fineberg, former president of the National Academy of Medicine, extolled the merits of evening out hospital admissions in Canada at a health policy speech put on by Alberta Innovates in 2014.

“You can work miracles on the flow of patients in the availability of resources and in the emptying of the emergency rooms,” Fineberg told his audience, which included officials from Alberta Health Services.

“This is something that can be done without a single dollar investment in capital.”

The University Health Network in Toronto, which runs the biggest surgical program in the country, adopted the Institute for Health Care Optimization’s method shortly before the pandemic hit.

It involved redistributing the workload throughout the week, making sure there were a similar number of cases that needed intensive post-surgical care each day, for example.

At the same time, the hospital defined how emergent different cases were and what resources would be needed to deliver the care.

Emergency surgeries also got dedicated operating rooms, so scheduled procedures could run full-tilt with limited unexpected interruptions.

The result was a more predictable schedule for OR staff, fewer cancelled surgeries, cost savings and more work getting done.

“It is the silver bullet in that we’re doing more than we’ve ever done with less, more efficiently,” said Dr. Shaf Keshavjee, chief surgeon at UHN and president of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, the world’s top academic society for cardiac and thoracic surgeons.

“We’ve created capacity to do more. So we are working at 105, 110 per cent.”

While the method can’t attract more nurses or offer a break to bone-weary doctors, it has allowed the Toronto hospitals to plow through backlogs accumulated during the pandemic more quickly.

“I can tell you our backlog has gone from 4300 down to 3200. We’ve cleared about 1,000 cases,” Keshavjee said.

And because Litvak’s method demands an accounting of what kind of resources are needed for which cases, Keshavjee also knows the backlog likely won’t be cleared until March 2023.

Keshavjee says the method isn’t without challenges, saying it requires a definite adjustment from staff.

“It is a culture shift and you have to do the work. Your hospital has to want to do it,” he said.

And although the system seems relatively simple, he says the approach adopted by UHN is relatively unique in Canada. Though that could change now that more Canadian health authorities are reaching out to Litvak since the emergence of the Omicron variant of COVID-19, which threatens to pull the country into another potentially massive pandemic wave.

Litvak desperately hopes more hospitals will consider putting his method to work to save both health-care dollars and Canadian lives.

“Given the new variant, it is very much needed,” Litvak said. “I just cannot watch what is going on.”

Discussion about this post