Every bean that ends up on Griffins Ochieng’s plate at Jaribu Primary School in northeastern Kenya can now be traced to a government warehouse where it was first stored.

And that’s the idea – that nothing must go to waste in Kenya’s school meals. With the World Food Programme’s (WFP) support, meals are integrated into the government’s National Education Management Information System – an online tool that automates the management of all data and processes in the education sector. It is a powerful example of ways cutting-edge technology can make a tangible difference in people’s lives – showcased during the International Day for Universal Access to Information.

“WFP has worked with software developers from the Ministry of Education to capture and digitize school meals records throughout the entire supply chain,” says Charles Njeru, WFP’s School Meals Manager in Kenya. “Authorized persons can access and scrutinize the data at any time.”

Kenyan authorities are now rolling out the initiative countrywide, with WFP supporting teacher training on how to update and track school-meals data. Jaribu Primary School, in Garissa County, is among those now ready to ditch manual registers for digital files.

Headteacher Mohamed Gedi is confident the new system will make work easier for his busy staff.

“I can update my records from any location,” he adds. “I also have a good visualization of the food allocation and the movement of stocks in my store.”

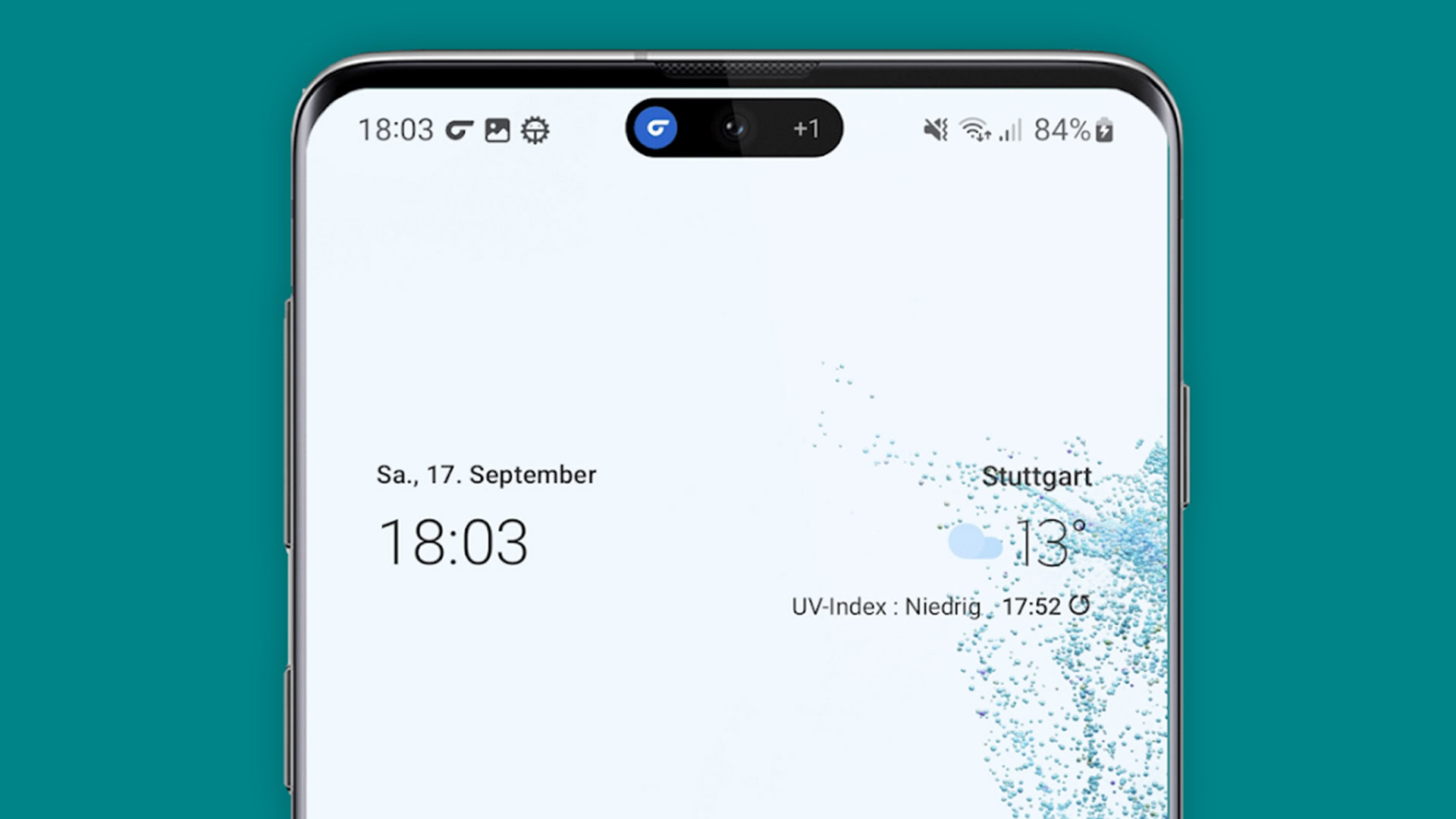

Educators like Gedi now have a mobile phone application on their smartphones, whose development was supported by WFP with the backing of the United States Department of Agriculture.

It is another example of how WFP remains in lockstep with every transition in Kenya’s school meals programme, which the Government took over in 2018.

A game changer

The mobile app is a major game changer, not just for school meals but for the entire tracing system. Educators in far-flung areas – where internet connections are often patchy or nonexistent – can easily update data such as enrolment, daily attendance and allocation of books, even when they’re offline. Once in a while, they connect to the internet for the data to be backed up.

The online tool is empowering teachers, Gedi says, since they know the supplies and exact quantities to expect from transporters. If there is a discrepancy, they can reject the consignment and raise a complaint. With the manual records, catching such discrepancies was nearly impossible.

“Every learner counts and every meal counts,” says Nereah Olick, Kenya’s Director of Primary Education. “Digitizing the school meals records will improve accountability and transparency in the overall management of the programme.”

Kenya’s school meals – typically hearty hot lunches consisting of maize or rice and beans, along with leafy vegetables – are critical in helping to keep children healthy and in the classroom. This is especially important right now, as the country’s worst drought in decades intensifies hunger – with an expected 4.35 million people facing acute food insecurity by October.

For Griffins, the Jaribu Primary School student who is now in grade 7, school meals are sometimes the only food he eats all day. He lives with his father, a security guard, in a single room near the school in Garissa town, the county seat.

“Sometimes, my dad lacks money for food,” he says. “Just last week, he didn’t have any cash. We slept hungry.”

Griffins wants to be a soldier. He puts on a stern look, perhaps to mimic the disciplined forces.

“I’m glad that we have lunch in school,” he adds. “It is a nutritious meal that gives me the energy to learn and grow strong. It will help me reach my goal in life.”

Wednesday 29 September is International Day for Universal Access to Information, promoting that everyone has the right to seek, receive and impart information. You can learn more here.

Discussion about this post