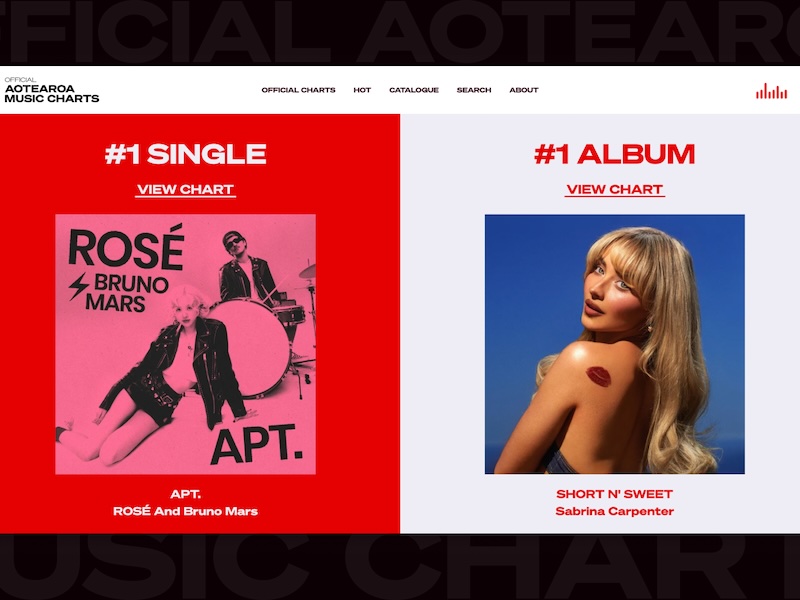

Tūpuna and karāpuna (ancestors) are laid on to Te Atamira (stage).

Photo: Te Papa

The remains of more than 60 Māori and Moriori have finally returned home, after more than 70 years of appeals and negotiations.

Many of the kōiwi had been stolen by a notorious Austrian grave robber in the late 1800s, and held for more than a century at the Natural History Museum in the Austrian capital, Vienna.

But at Te Papa in Wellington on Sunday morning, they were finally returned in a ceremony at the museum’s marae.

The sound of the karanga and putatara carried across the mist-cloaked harbour, the squally rain whipping onto the korowai, kahukiwi and garlands that adorned those who’d come to greet their long-lost whānau.

Box after beige box was carried onto the marae, as wailing and sobbing filled the air. Tears of a century of pain, anguish and, now, joy. Sixty-four tūpuna are home.

Iwi delegation arrive on to Rongomaraeroa, carrying the tūpuna and karāpuna through the waharoa and Ranginui doors at Te Papa’s repatriation pōwhiri.

Photo: Te Papa

Te Papa’s Repatriation Advisory Panel chair Sir Pou Temara, in a sharp pinstripe suit, said their loss was a weight that had been borne for a century.

“There’s no closure,” he told RNZ.

“In our culture, the dead is part of our living. We keep our ancestors close to us all the time, and if they’re not close every effort is made to ensure we bring a balance.”

An effort that had been made by Māori and Moriori for more than a century.

The 64 tūpuna returned on Sunday came from across the motu, tūpuna Māori from Tai Tokerau to Ngāi Tahu, but also karāpuna Moriori from Rekohu.

The majority of them – believed to be 49 – had been stolen by the notorious taxidermist and grave robber Andreas Reischek, who spent 12 years here in the late 1800s.

He travelled the country taking interest in fauna, flora and indigenous people, even befriending Kiingi Tawhiao, who allowed him to hunt for different species of birds. This trust was betrayed when Reischek took ancestral remains, a pattern repeated across the country.

In his diaries, he boasted of eluding Māori surveillance, looting sacred places and breaking tapu.

“It is one of the most difficult tasks, because all these places are tapu, holy, and no one is allowed to enter them without being noticed by the locals,” Reischek wrote in one entry from 1888.

“Early morning to evening, especially when they’re mistrusting.”

Hona Edwards (Te Uri Roroi, Te Mahurehure Ki Whatitiri, Te Parawhau) at Te Papa’s repatriation pōwhiri.

Photo: Te Papa

Te Papa Kaihautū Arapata Hakiwai said the kōiwi were then taken to Vienna, where they were kept at the Natural History Museum for 130 years. But their loss was never forgotten, living on in the kōrero and grief.

“During the [Second World] War the Māori battalion actually knew our ancestors were in the Vienna Museum and they wanted to go get them, but it didn’t happen,” Hakiwai said.

“So from 1945 right through to this time we’ve had a period of requests, if you like.”

That first request from Māori came at the end of the war, but the New Zealand government did little to raise it until decades later. Even then, there was little headwind.

In 1985, the late Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu led a delegation to ask for them back, which started a flow of remains back from Austria. Sunday’s was the biggest so far.

Vienna Natural History Museum head of anthropology Sabine Eggers said Austria – like some other European countries – was now in the midst of a reckoning with its colonial past, where holding on to stolen taonga and kōiwi was no longer acceptable.

“One thing is that in Europe, finally, these issues are getting really discussed in the museum,” Dr Eggers said. “These issues have been neglected.”

Now, finally, the tūpuna are back.

Tūpuna and karāpuna (ancestors) are placed on to Te Atamira (stage).

Photo: Te Papa

They are being stored in the wahi tapu space at Te Papa, but efforts are underway to identify where each kōiwi came from, so they can finally return to rest on their whenua.

Ngāti Wai kaumatua Taipari Munro was at the ceremony on Sunday. Kōrero about what happened has been passed through generations, as has the fight to get them back, he said.

His ancestors were taken from across the Ngāti Wai rohe, on the east coast of Northland.

“Battlefields in my tribal territory, but also from burial grounds and burial caves in my territory.

“So this why my people and I are here today, many of the tribes have known for a while that activity of his. Not only of Reischek’s, but of others as well.”

Iwi representatives at Te Papa’s repatriation pōwhiri.

Photo: Te Papa

Sir Pou said there is still much more to do. Sunday saw 64 kōiwi return from what are believed to be hundreds held in museums, institutions and private collections across Europe and North America.

Sir Pou, who has been on the repatriation panel for 20 years, said attitudes still needed to shift both here and abroad.

“What we have repatriated is only a small percentage of what we haven’t got back. We still have to wander and find out where our ancestors are.”

Discussion about this post