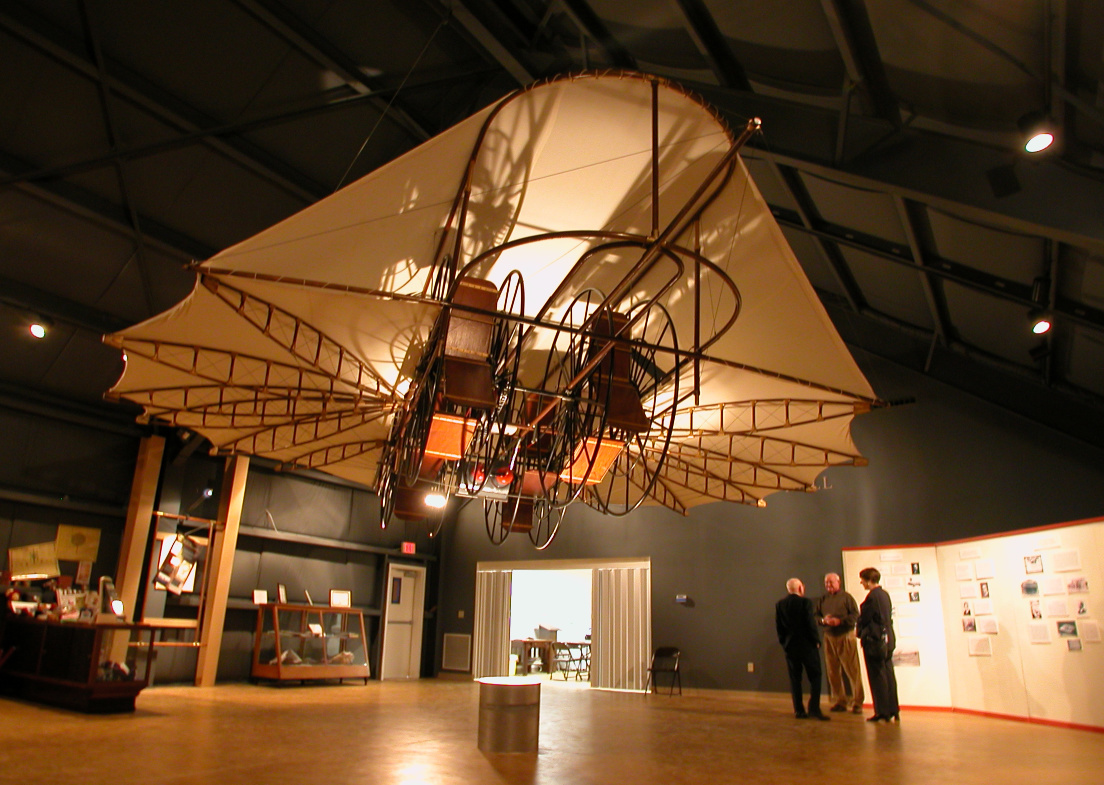

A replica of the Ezekiel flying machine is displayed at the Northeast Texas Rural Heritage Center and Museum in Pittsburg. Photo by Will van Overbeek.

The turn of the 20th century was a time of technological dreams. The harnessing of petroleum had spawned the automobile, as well as the hope for something greater—powered, controlled flight. All sorts of weird-looking “flying machines,” as they were then called, were emerging from workshops around the world. One of the weirdest arose, perhaps literally, from a pasture in Pittsburg, the work of sawmill operator, inventor, and part-time Baptist preacher Burrell Cannon.

It looked like a giant nun’s cornette, undergirded by a metal frame, a gas engine, and wheels 6-feet in diameter. He took his design inspiration from the biblical book of Ezekiel. Some say that in 1902 this contraption flew 10 to 12 feet off the ground for some 160 feet, passing over a fence from which panicked gawkers fled, to land in a meadow. If it happened, it was a year before the Wright brothers historic flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. And Cannon may not have been there to see it.

He’d come from Mississippi, seeking something East Texas abounded in—virgin timber. For seven years, in the tiny Northeast Texas town of Pine, Cannon operated a sawmill. In 1900 he sold it and moved to nearby Pittsburg—a larger community—with a big idea and enough personality to sell it. He raised $20,000 in capital from investors and the Ezekiel Airship Manufacturing Company was born.

Despite how it may sound, Cannon was no huckster. He was a true believer, a woodsy-renaissance man who’d grown up on a farm, fascinated by machinery. He’d studied mechanics at Mississippi College, spoke multiple languages, and held patents on inventions such as a marine propeller and a windmill. He preached in his spare time. He set up shop inside a Pittsburg foundry and went to work.

The plan for the airship incorporated ideas from an Old Testament prophecy in which living beings would rise into the sky on wheels inside of other wheels. In Cannon’s take on the scripture, he gave his airship pairs of matched wheels—inner and outer—that spun in opposite directions. The inner wheels had paddles for blowing air into the canopy to create lift. Pilot controls could maneuver the paddles to add forward thrust.

One Sunday in late 1902, the exact date is unknown, some of his workers rolled the airship out of the workshop for a test run. Accounts vary, but most say Cannon was off preaching at the time. No verifiable record of the flight exists, just witness accounts that have filtered down through the years. The craft is said to have shaken violently and sustained damage upon landing.

With investors clamoring for more results, and Cannon pressing for more money, he eventually packed the Ezekiel onto a train. He was thought to be heading to the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, where a prize was on offer for advances in flight. Somewhere near Texarkana, a powerful storm arose, blew the machine off its flatcar and crushed it.

Years of dreams and sweat were left scattered in the dirt, but Cannon didn’t give up. He built a new flying machine that wrecked in a test flight. By this time the Wright brothers triumph at Kitty Hawk had taken the whirl out of Cannon’s propellers, so to speak, and he pivoted to more earth-bound inventions. He died in 1922, age 74, working on a cotton-picking machine and boll weevil destroyer.

Though he missed out on the history books, Pittsburg didn’t forget Cannon. In the 1980s, the Pittsburg Optimist Club built a full-size replica of the Ezekiel from a surviving photograph, the original plans having been lost in a 1922 fire. Today it hangs from the ceiling of the Northeast Texas Rural Heritage Center and Museum on Marshall Street in Pittsburg. Volunteer docent James Olson affirms it’s the most popular exhibit—“Our big claim to fame,” he says—one that has drawn visitors from as far away as South Africa, inviting all of them to gaze up and recall a time when one of humanity’s oldest dreams was coming within reach.

Discussion about this post