In a 2005 episode of The Office, Michael Scott, the office manager, requires his employees to choose an upside-down index card from a tray and place it on their forehead. The cards bear a racial or ethnic label—Black, Jewish, Italian, and so on—and Michael tells the employees to treat one another according to the label listed on the card and to “stir the melting pot” by playing to racial stereotypes. The scene, which ends with Michael getting slapped in the face, mocks corporate America’s ham-handed approach to diversity training. Back in 2005, almost no one saw the C-suite or the human-resources office as an engine of progressive change. Indeed, the idea that workers would look to their employers for leadership on any delicate social or political matters seemed risible.

Yet, today, a new status quo has emerged.

I am a political scientist and am currently researching how business leaders and their companies shape American politics. But while interviewing dozens of executives from across the country, I could not help but notice the ways that American politics is also reshaping corporate life.

Donald Trump’s presidency led companies to start regularly issuing political statements on major developments in the news. In 2020, the murder of George Floyd, and the subsequent protest movement, prompted companies not only to incorporate more diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives into the workplace, but also to adopt “anti-racism” messaging, for which merely showing tolerance wasn’t enough. Participants are urged to actively promote anti-racist policy goals—rendering these sessions far more overtly political than their predecessors of the 1990s and early 2000s.

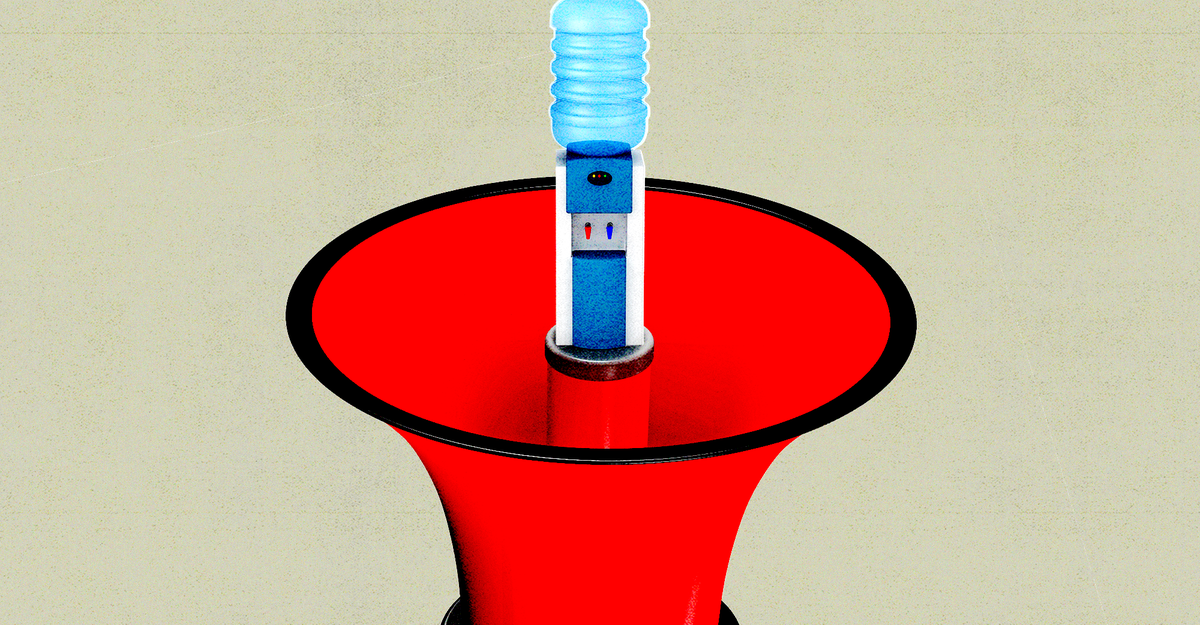

Although political chitchat has always been part of office culture, the volume of the discourse and the extent to which it is coming from management are departures from the past. As a senior manager at a New York insurance firm recently told me, “I probably get just as many emails” from the company’s executives “about social-justice or environmental stuff as I do about how the company is doing. And that’s just not how it was … That’s a major shift that’s only happened in the last two or three years.” Bosses across the country, particularly in white-collar workplaces, are pumping out tweets and press releases about the midterm election, abortion rights, and the war in Ukraine. They are hosting mandatory trainings and workshops that come uncomfortably close to the TV parody.

But if anything, the new normal likely hinders the cause of diversity and tolerance, while producing no other worthy social change. Mandatory workshops on anti-racism and LGBTQ rights are about as effective at eliminating bias as you’d expect if they were facilitated by someone from The Office. Political messages issued by corporations are intended to sound topical, progressive, and genuine, but come across to many listeners as tone-deaf, performative, and alienating. Companies, I think, should be politically and civically engaged, but they’re going about it all wrong.

At many white-collar jobs, workers have extra time on their hands. Social-media scrolling, gossip, needless group meetings, “quiet quitting”—the inefficiency of office culture is old news. But politics appears to be sucking up more of that time now than in the past.

Three factors are at play. First, the white-collar workforce has undergone a partisan realignment. Workers with four-year degrees now vote overwhelmingly for Democrats. Democratic voters now trust business more than Republicans do. Democratic workers are enthusiastic about businesses taking public stands on political priorities. CEOs themselves, who tended to be somewhat apolitical on social issues before Trump’s 2016 victory, have in some cases made headlines by becoming activists. And they have hired vice presidents and consultants who keep the company’s social mission high on the agenda. In short, white-collar businesses have become Democratic constituencies.

Second, the long-running decline of civic life in America, likely exacerbated by COVID, means that many Americans who are cognitively engaged in politics lack any social organization—other than the office—through which they can channel their political energy. Many people who consider themselves political junkies don’t volunteer for candidates’ campaigns or advocacy groups. They aren’t active members of unions or religious communities or neighborhood associations.

CEOs are complicit in turning the office into a venue for political discourse. A real-estate developer in Georgia recently told me about how he gathers his team, including maintenance personnel as well as data analysts. (Because I conducted these interviews in my capacity as a political scientist, I am not identifying my interviewees by name, in keeping with ethics standards in social-science research.) They meet on Zoom, pick an issue in the news, and talk it through. These conversations are an attempt to push back against political polarization. “I [want] all of us to talk to each other as Americans and fellow citizens and being part of the same team,” the developer said. He described these meetings as therapy sessions through which he, the boss, in his own small way, can try to heal America’s political wounds.

The third factor behind the politicization of the workplace is a cultural shift in corporate leadership and in employees’ expectations of their managers. If workers come to the office with low morale because of an election loss or Supreme Court decision, today’s bosses are not going to yell at them to buck up and get back to work. Bosses have learned to be empathetic leaders who need to care about what workers care about.

Since the Great Recession, the conventional wisdom among corporate recruiters has been that workers, especially young workers, want bosses who have a sense of mission and whose political positions align with their own views. In this account, socially conscious people don’t want to work for a company that cares only about money or that contracts with nasty clients or that donates to members of Congress who support the wrong positions. Workers know that companies can exert pressure on politicians. The company can have a bigger impact than the workers can have alone through their personal Facebook posts.

And yet politicizing the workplace—either to meet employees’ demands or to satisfy the CEO’s political goals—has obvious pitfalls. Not every worker or boss is good at respectful dialogue about political matters. A conservative executive in Texas told me this summer that he had to buy out his even more conservative business partner because the partner had embraced COVID conspiracy theories and engaged the staff in politically aggressive, emotionally obtuse conversations.

More fundamentally, the boss-employee relationship makes the workplace a difficult setting for an open conversation about politics. An office is not a community of equals. When a boss injects politics into a conversation, many employees feel compelled to nod along, which gives the boss a false impression that everyone feels the same way.

Feigning agreement with the boss extends beyond explicit political conversations and into politics-adjacent subjects such as diversity, equity, and inclusion. One executive told me he sees diversity differently from how his employer sees it. “We just like diversity in the way people look,” he said of his company, “not diversity in the way people think.” The firm, he argued, hires people from across the racial and ethnic spectrum, but they come from a narrow set of universities and tend to hold the same liberal viewpoints.

This man, a Republican, tends to keep his opinions to himself, and for good reason. In a 2021 Knight Foundation survey that I helped design, 57 percent of Democrats (and a much higher proportion of Black and Latino Democrats) said private employers should prohibit workers from expressing “political views that are offensive to some.” Most Republicans disagreed. Speaking honestly at a DEI training or in a political discussion is difficult if most of your co-workers think your views not only are wrong but perhaps should be banned from the office.

Some forms of political engagement at the office have distinct and understandable goals. Workers want to have a say in how the firm does business; employers want to show that they care about the demands of customers and staff. But some of today’s political office culture does not even pretend to be strategic. Workers might gather around a TV screen to commiserate during major news events or fish for approval by sharing news articles in the employee Slack channel. Such activity functions as group therapy during political ups and downs. It does not change election results. It is pure political hobbyism—a performative form of civic engagement that has become the white-collar set’s preferred approach to public affairs.

Outside white-collar office culture, different norms prevail. In my interviews with industrialists and retailers, a wildly different perspective is evident. “You are talking about a problem that is just utterly foreign to my little world,” an executive who oversees a chain of beauty salons told me recently. He describes his firm as a “working-class, southern, multicultural company” with an entirely female retail staff. He views political talk at work as a frivolous distraction.

Even so, this executive has a clear vision of his company’s civic mission: offering a path into the middle class for people without strong educational credentials. “I feel very good that there are 150 women, most of whom come from crappy backgrounds, who have a shot at owning a home, buying a car, going on vacation.” His retail employees—none of whom has a college degree, he says—earn up to $90,000 a year. He thinks they are “likely to become Republicans” because their foremost concern is about money and taxes. “Our workers are tied to their own productivity. And that clears away an awful lot of crap.”

Of course, I do not know whether his employees feel the way he feels. But I understand why this executive looks on bemused at his post-materialist big-city compatriots. How many management consultants, tech engineers, corporate attorneys, or investment bankers can argue so forthrightly that their own firms are making other people’s lives better?

I am deeply skeptical of what the current wave of white-collar political hobbyism will accomplish, especially when so many corporate pronouncements are clearly hot air. (Consider those companies that very briefly, and very loudly, swore off donations to politicians who voted against certifying the 2020 election, and then very quickly, and very quietly, went right back to contributing to them.) The shame is that businesses and their employees can involve themselves productively in politics. They can invest time in community organizations and business organizations that have concrete goals and strategies. Rather than playing to would-be activists on Slack, business leaders can get involved (and try to involve employees) in long-term engagement on education, housing, transit, and other issues central to a thriving economy. They can encourage diversity and mutual respect by inviting workers to collaborate on common goals, rather than through stilted training exercises better suited to The Office.

How has white-collar office culture become so political? Ultimately, through the good intentions of people who recognize that all is not well with America today. Channel those good intentions into strategic civic engagement, and a company can make a difference. But if, in the end, the goal is merely to cultivate a mild sense of political camaraderie so that a certain class of partisan employees can feel better about themselves, then the virtuous email from the CEO and a monthly guest speaker introduced by the VP for DEI will probably do the trick just fine.

Discussion about this post