For a certain kind of book nerd, Rare Book School at the University of Virginia is the closest a person can come to Valhalla. Each summer, bibliophiles from all over the world gather for weeklong courses in nearly every aspect of the history of the book, in an atmosphere that combines deep immersion in the most arcane aspects of printing, binding and bibliography with the let’s-put-on-a-show camaraderie of a sleepaway camp.

But in the meantime, an exhibition at the Grolier Club in Manhattan gives the rest of us a taste of the school’s distinctive hands-on methods, along with a sweeping history of more than 2,000 years of bookmaking.

“Building the Book from the Ancient World to the Present Day,” on view through Dec. 23, draws on the more than 100,000 items in the school’s teaching collection. There are printing blocks, binding tools, ink brushes, paper samples, printer’s proofs, strange contraptions and of course plenty of books, from a Japanese Buddhist sutra to a dinged-up copy of Madonna’s “Sex.”

If there’s an overarching lesson behind the show’s deceptively dry title, it’s that every book, whether an exquisite rarity or the humblest of battered paperbacks, tells a story — even before you actually start reading it.

“There’s so much history and so many stories that lie on the surface,” Barbara Heritage, Rare Book School’s associate director, who curated the exhibition with Ruth-Ellen St. Onge, said in an interview. “There are amazing narratives these books carry as vessels.”

The items on view range in size from a tiny volume of Abraham Lincoln speeches, less than an inch tall, made around 1929 by students at a Tennessee press, to a leaf from a massive double-elephant-folio edition of John James Audubon’s “The Birds of America” — a literal monument of bookmaking.

There is also a 19th-century memorandum book made of nearly translucent ivory (for easy erasing), a miniature almanac concealed in a wooden case carved and painted to look like a bread roll (created as a calling card for an 18th-century Viennese bookbinder), and a roll of binding-ready reindeer skin that was harvested by Sami people in the 18th century, lost in a shipwreck and then rescued 200 years later, still redolent of birch oil.

“We have photographs of students just smelling it,” said St. Onge, who was until recently the collection’s associate curator.

And then there’s “On the Slates,” a 1992 experimental book by Clark Coolidge. It consists of poems printed on dollar-bill-size sheets, which are rolled up in actual dollar bills overprinted with the press’s address, tied together with a shoelace and tucked inside a battered men’s shoe nestled in a shoe box.

Is it really a book?

“One of the things we want the show to do is really challenge the idea of what a book is,” Heritage said.

What a book is has certainly changed over time, as clay tablets, papyrus scrolls, parchment and quills have given way to codexes, movable type, mechanized printing processes and e-readers. But book history isn’t a story of linear progress, the show emphasizes, but of different technologies and forms coexisting and overlapping.

And it’s also not just a Eurocentric narrative. The show (which also exists in an online version) includes a Tibetan samta (a wooden tablet with a reusable surface), a Sri Lankan ola leaf manuscript, and a group of Ethiopian wood-encased manuscript Bibles, as well as early printed books from East Asia, where movable type was developed centuries before Gutenberg’s press.

A distinctive aspect of Rare Book School is its dedication to “tactile learning,” as the exhibition’s companion volume puts it. Rather than peering through glass, students handle objects — sometimes as many as 500 in a single course.

The show highlights the school’s spirit of detection, and the way students learn how (and when, and where) books were built by — literally or metaphorically — taking them apart.

There are samples of the teaching kits assembled by the school’s founding director, Terry Belanger, which include samples of type, or of printed illustrations made through different processes. There’s a replica of an 18th-century paper mold, which is used to teach students how to date paper by analyzing watermarks, lines and other identifying characteristics. (Look closely enough, and it’s theoretically possible to trace a sheet back to a particular mold in a particular mill.)

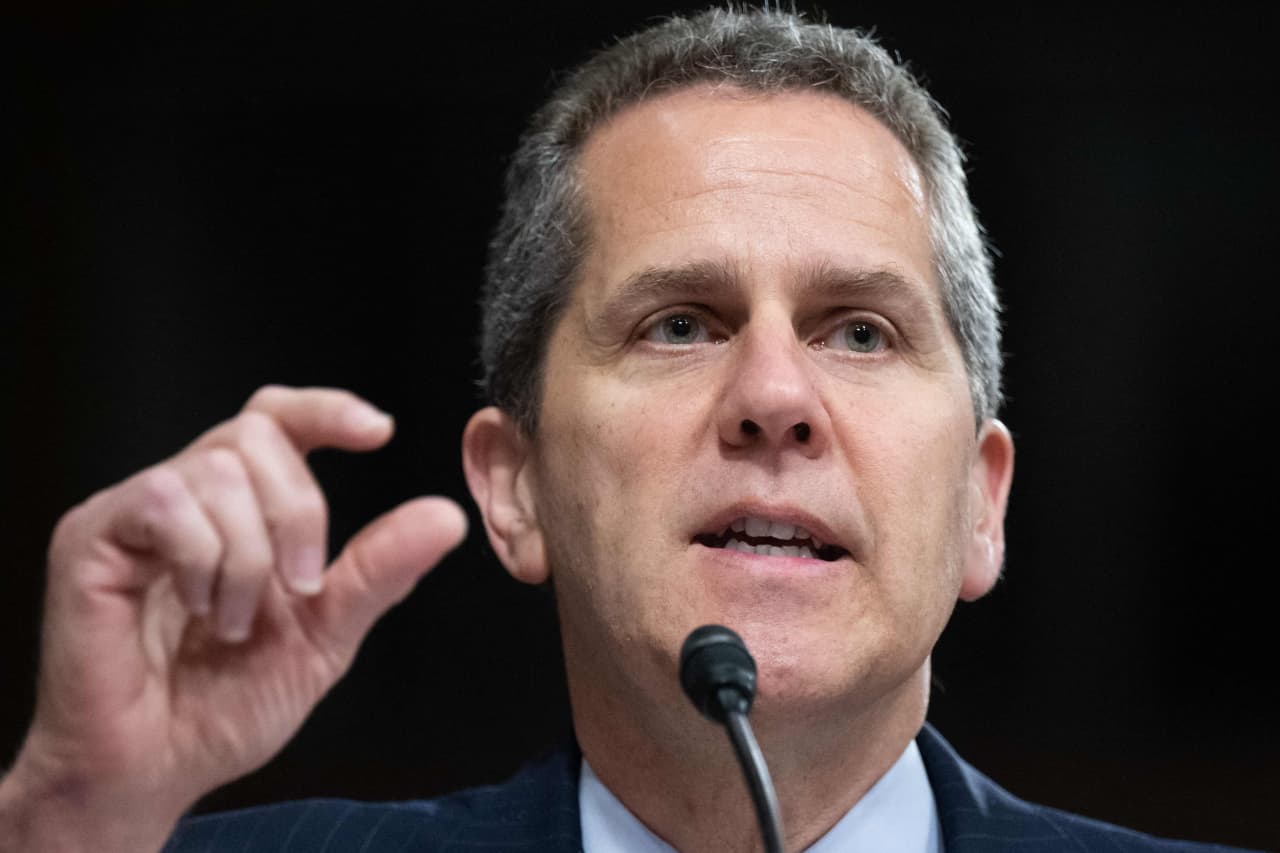

Students learn to distinguish printed medieval texts from manuscript ones, an original print from a restrike, the real from the fake. Among the regular course offerings is Facsimiles, Forgeries and Sophisticated Copies, taught by Nick Wilding, the early modern scholar who recently determined that a prize Galileo manuscript at the University of Michigan is a 20th-century forgery.

Rare Book School, whose current director is Michael Suarez, has had its own share of dramatic aha moments. The show includes a fragment from the 1459 Mainz Psalter, the second-oldest dated piece of printing from movable type in the West. (Only 13 intact copies are known to survive, making it rarer than the Gutenberg Bible.) The fragment was discovered in the 1920s in another book, where it had been used as binding scrap. It arrived at Rare Book School as part of a donated box of random manuscript scraps, and was quickly recognized by a visiting expert as printing.

And then there are the more modest needle-in-a-haystack discoveries. Take the set of wood-engraved blocks showing frolicking elephants, which Belanger bought on eBay in 2004.

“He said, ‘We’re never going to find a book printed from them,’” Heritage recalled. “I said, ‘I think we can.’”

Heritage noticed some residue in the grooves — plaster of Paris, a clue that they had been used in a stereotype printing process developed in the 1830s. After some deep dives into Google, she located an 1845 edition of a children’s book called “Stories about the Elephant,” one of only 10 copies known to survive, in a dealer’s catalog. The prints matched exactly.

The show speaks to the enduring power of the book as a bedrock of cultural memory, for all its shape-shifting. But it also includes some books that will never be read, because they’ve become literally unreadable.

Take “Gutenberg,” a 2002 artist’s book by Edward Bateman. It consists of eight letterpress-printed pages, between covers made of two computer zip disks, which hold digital versions of “The Odyssey,” “The Canterbury Tales,” “Hamlet” and other canonical works.

Or at least they used to. Within five years, the printed text explains, the disks will begin to break down, and “the books will begin to disappear.”

And then there’s a poignant “friendship album,” made in Nebraska around 1892 using a store-bought notebook, bound in a hand-sewn velvet cover. Each page is folded down and fastened shut with thread, buttons, ribbon and even a toothpick, with handwritten directives like “Open when feeling down hearted” or “Open when you get to California.”

Many pages are still sealed, and will stay that way. And there’s a story in that, too.

“It’s like an unopened door,” Heritage said. “Why did the reader not open it? What happened? We can only speculate.”

Building the Book From the Ancient World to the Present Day

Through Dec. 23 at the Grolier Club, 47 East 60th Street, Manhattan; 212-838-6690, grolierclub.org.

Discussion about this post