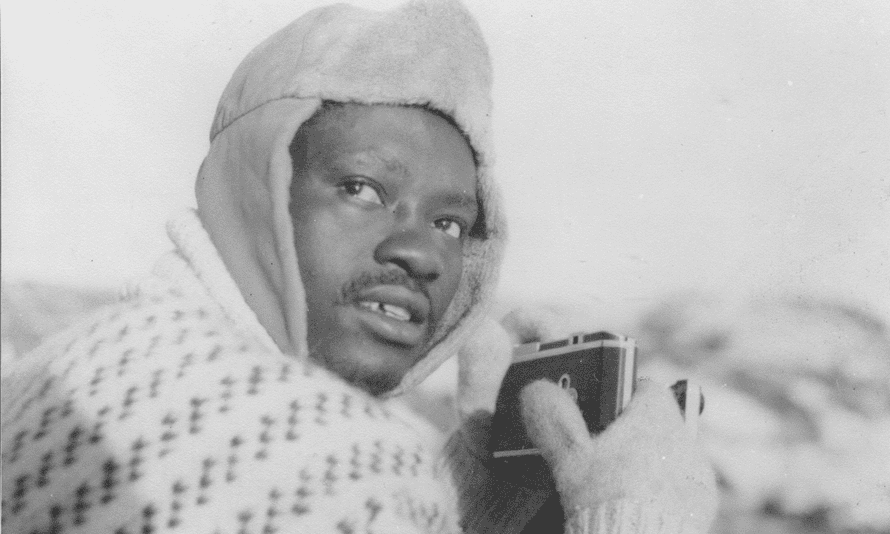

The warm living room of Tété-Michel Kpomassie’s otherwise neat Parisian home has a coffee table in the middle of it piled high with keepsakes – a mountain of black and white pictures, letters and handwritten diaries. It’s an archive of one remarkable man’s intrepidly adventurous and unconventional life to date. Balanced on top of the overloaded files and folders sits a tattered book, its pages faded. On its cover is a portrait of an Inuit in a sealskin jacket, standing next to an icy shore. The title reads Les Esquimaux du Groenland à l’Alaska (The Eskimos from Greenland to Alaska). It’s a 1947 work of nonfiction authored by French anthropologist Robert Gessain.

Decades may have passed since the day Kpomassie first set his teenage eyes upon this image in his native Togo, but the 80-year-old remembers the precise moment as if it had happened just minutes before. How could he not? What he found inside has, since that day, consumed him entirely, shaping every chapter of his own story. He ran away from home at 16 to embark on an epic cross-continental mission that delivered him to Greenland, the world’s northernmost country. He was the first African man to set foot there. The adventure resulted in a travelogue, return visits and countless speaking invitations, and, more recently, a rather acrimonious divorce. Now, his very own sealskin jacket hangs by the door to his home in pride of place.

Quite what an academic study of Inuit peoples was doing on the shelves of a small Christian missionary bookshop in 1950s Lomé remains a mystery. Kpomassie stumbled across it while recovering from a tree-top run-in with a snake. The only explanation he can think of, after years of contemplation, is that finding it was his destiny – an undeniable consequence of some predetermined fate.

“I picked it up, not understanding the words in front of me,” Kpomassie says, his eyes lighting up as he recounts that morning. “But the man on the cover was smiling right at me. We had a connection, an exchange.” Intrigued, Kpomassie bought the book, sat on the beach and devoured it from cover to cover. Once finished, he read it again and again.

“From the minute I completed it,” he says, “I never stopped thinking of Greenland, my country. It was resonating inside me. I don’t understand it. But a magnet was pulling me, so I packed my bags and left, in secret.”

The journey which followed is barely believable. If it weren’t for the artefacts laid out in front of me, I might question whether it was a fairytale dreamed up in his mind. It was a trip that saw him traverse Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mauritania and Senegal. There were brief stops in Morocco and Algeria, before he finally disembarked a boat in the south of France. From there, his voyage through Europe was facilitated by the endless kindnesses of strangers and, in particular, the generosity of Jean Callaut – to whom Kpomassie’s own book is dedicated. Callaut was a Frenchman who soon became an adoptive father to the young traveller so far from home. “When people heard my story,” Kpomassie says, “each was certain they were dealing with someone very determined. But if they hadn’t helped me, be in no doubt, I’d have found another way.”

Just before noon on 27 June 1965, the boat Kpomassie had boarded in Copenhagen eight days earlier docked in Qaqortoq, a small town in southern Greenland. Eight years had passed since he’d first said goodbye to Togo. And, finally, Kpomassie – now aged 24 – had arrived in his new home.

“It was fantastic,” he says, all smiles. “From the ship’s porthole I could see all the people gathering at the harbour waiting for our boat to arrive.” In the hull were supplies, namely coffee and alcohol, that locals had been waiting all winter for. Little did they know that on board was also a surprise of another kind.

“I took my time to step out,” he continues, “uncertain of how people would react to seeing me. I suspected none would have met a black man before. When I did, everyone stopped talking, all were staring. They didn’t know if I was a real person or wearing a mask. Children hid behind their mothers. Some cried, presuming I was a spirit from the mountains.” One woman, he later learned, yelled “handsome” in his direction from the crowd.

Of course, the Arctic climate and landscapes he encountered as he moved through the country were total opposites to those of Togo. And he was intrigued by the cultural differences, too. “The way each place treated children struck me early on,” he recalls. “In Togo, kids were treated as the subjects of their elders, with strictly enforced hierarchies. In Greenland, meanwhile, parents obeyed their young.” In the book he later wrote, Kpomassie examines and contrasts the customs of his two homelands, looking at their respective treatment of the elderly, rituals for hunting, prayer and death, as well as familial structures and non-monogamy, which in both places was markedly different from modern European ways. And then there was the food, the intensely spiced dishes he grew up eating were a far cry from the boiled seal he was served up night after night, and raw fish eaten straight from the ocean.

In time, however, Kpomassie came to consider the two nations’ similarities which, in his mind, also bound them together. Doing so helped him see his own desire to leave Togo in a different light. “I left because at that time I had been made to hate my culture, because of what was happening in Africa,” he says. When he left Lomé, the country was still under French colonial rule. “Christians tried to convert my father,” he says. “African names were banned and we were forced to take Christian ones before being admitted into schools.”

What Greenland promised, Kpomassie hoped, was a life free from this violence, where traditions and customs were left to thrive. “The problem was, I discovered that Greenland was also a colonised country,” he says. “Its culture was already being diluted by European influences. They worshipped their sea god, but here missionaries undermined local beliefs, too.”

It was only in the northernmost places he visited that Kpomassie would find the freedom he’d been searching for. If anything, he was disappointed by what he found at first in the south. “There were no igloos, no hunters or huskies,” he says. “Everyone was always drinking beer and coffee, and buying Danish food from the department store. After eight years of travel and thousands of kilometres, it dawned on me that arriving in Greenland was only the start of my journey. Because when I asked my hosts where the Inuit igloos and seal-hunters were, I was told to go to the far north.”

It was only up there, as autumn and then winter settled in, when the country and its people were plunged into a seemingly endless polar night, that Kpomassie felt he’d truly arrived. “When the first snow falls,” he says, “You see the real Greenland. With the temperature dropping rapidly and, the sea freezing up, that’s when Greenlanders become the kings of their country. Outsiders vanish, age-old knowledge prevails. It’s that liberation I loved the most.” Under the aurora borealis, as far from Africa as he’d ever been, Kpomassie at last found his light.

Today, Kpomassie lives in Nanterre, a historic suburb to the west of Paris. Despite being more than 50 years his junior, I struggle to keep up, with both pace and conversation, as we make our way to a nearby restaurant for lunch. As it transpired, Kpomassie tells me, his first pilgrimage to Greenland wasn’t permanent. Only 18 months after arriving, he reluctantly returned to Togo, to share his stories with his compatriots and the family who’d long presumed him dead.

“At first,” he says, scanning the wine list, “when I came back from Greenland, I wanted to throw my diary into the sea. I did not want to write a book.” His experiences felt private, almost sacred. “In fact, I didn’t even want to leave, but I couldn’t get the right boat at the right time to head further north. So I toured 16 African nations giving talks. I wrote the book. I somehow got married in France and had two children. But all the while I knew where I ultimately needed to end up.”

More than 40 years have passed since his book was first published in French. Since then, there have been a further 22 editions in 10 languages. A new English one arrives this year, with Portuguese and Mandarin versions in the works, too. No doubt its longevity can be attributed to Kpomassie’s skilful storytelling, but it’s by no means the only reason his work has stood the test of time. While many similar travelogues from decades past, written by “explorers”, now feel dated – Eurocentric, patronising or exoticising of their subjects – Kpomassie’s couldn’t be more relevant. The kinship he felt with Inuits on that first visit saw the publication of a literary work that was well ahead of its time.

Since then, Kpomassie has returned a further three times to Greenland, his most recent visit as a lecturer with a Norwegian cruise liner back in 2007. This September he’ll make one final journey to his adoptive nation, where, at 81, he intends to live out his remaining years. Through all the decades since, this has been his plan, he says. Unfortunately, that’s why last year he and his wife of 46 years – the mother of his children – divorced, going their separate ways.

“I was married for a long time, but sadly our separation became inevitable,” he says. “She knew from the beginning that Greenland is the most important thing in my life.” The deal, he says, was always that they’d one day swap their comfortable life in France for a retirement spent hunting in the shadow of Greenland’s mountains. At some stage, Kpomassie’s ex-wife – now a grandmother – not unsurprisingly, changed her mind. It created an irreconcilable gap. “Now, she wants to spend her retirement visiting Rome, Florence, Venice,” he says, a little indignant. “From the offset I was honest about where my heart was. We’d always agreed to go together. I understand, of course, that her wishes changed. But mine haven’t.”

And what do his children make of it all? Well, they’re not hugely impressed. Kpomassie thinks his big mistake was telling them his intentions in the first place. “If I’d told my family as a 16-year-old, I would never have left Togo,” he says. “Everyone would have tried to reason with me, to stop me. Now my sons are doing the same, but that’s not what I want. My children admire me, but they are afraid, and they feel they should discourage me.” He’ll miss them, he says, but his door will always be open should they wish to come and visit.

On arrival in Greenland, Kpomassie hopes to spend a year travelling the country, giving talks to schoolchildren about his adventures in their country and across Africa. Then he’ll head north, where he’ll stay for good. “I’ll have a dog sled and huskies,” he grins. “I’ll find myself a small fishing boat. And here I’ll happily spend my remaining days, and finally find time to write my second book, about my childhood in Africa.”

That is, of course, if the authorities allow it. At present, aside from locals, only Danish people are allowed to buy property in Greenland. “I think they might make an exception for me,” he says, winking. “Well, at least I hope so.” He wants to be buried at the foot of an iceberg. “In African animism, we believe in spirits in trees, the sea and mountains,” he continues. “Greenlanders also believe icebergs have a soul. Sitting and staring at the icebergs I can converse with these spirits. I find my ancestors in Africa, but I find them in Greenland more.”

Coping without life’s luxuries will be no trouble, Kpomassie assures me, as a waiter delivers him a plate of duck breast and refills our glasses with Côte du Rhône. “All this? It’s superficial,” he says. “The day I put on my sealskin anorak hanging in my hallway, I’ll forget it all and say goodbye. It’s just to survive, I’ve had to adapt. When you pursue a dream,” he continues, eyes twinkling, “one which has grown with you for an entire lifetime, you live and breathe it. It’s inside me. Fulfilling it is not a choice. Anyone would have said my first journey there would be impossible, but I proved them wrong. Why should it be any different this time just because I’m older? It’s my destiny. There is no other way.”

Michel the Giant: An African in Greenland, Penguin Modern Classics, £9.99, or £9.29 from guardianbookshop.com

Discussion about this post