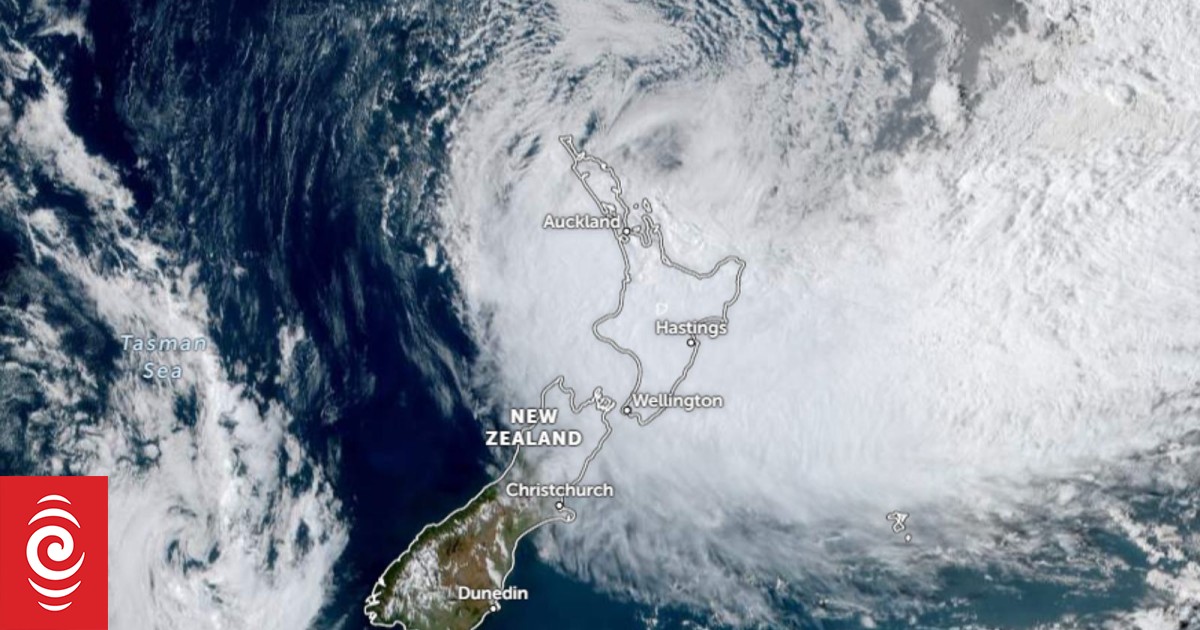

A satellite image showing Cyclone Gabrielle over New Zealand on February 13, 2023.

Photo: Zoom Earth / JMA / NOAA / CIRA

It has been a soggy few weeks for the upper North Island, with late January’s Auckland downpour and now, Cyclone Gabrielle.

States of emergency have been declared across Ikaroa-a-Māui, schools and non-essential services shut and public transport in the country’s biggest city running at a minimum.

Forecasters knew early on Gabrielle would be serious, prompting Auckland Mayor Wayne Brown to pre-emptively extend a state of emergency already in place to handle the previous month’s record rainfall and subsequent flooding.

“This summer just keeps on giving to the top of the North Island,” said Dr Dáithí Stone, a climate scientist with the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA).

“Each summer, Northland and Auckland are usually on the verge of drought, with a pretty severe one experienced just three years ago. Not this summer.”

Photo: RNZ / Nick Monro

So what has changed?

“Tropical cyclones feed off of the energy provided by hot ocean waters,” said Stone, noting recent summers – including the one we are in now – have seen “unusually warm water in the Tasman Sea and around Aotearoa”.

“This warm water is partly an effect of the warm ‘La Niña’ waters spanning the western tropical Pacific and partly some local ocean activities happening in the Tasman Sea, but the ongoing warming trend from human-induced climate change is playing a big role too.”

La Niña is an atmospheric phenomenon that usually happens every few years, when winds blow warm surface water from the eastern Pacific Ocean towards Indonesia.

In New Zealand, the result is “moist, rainy conditions” in the north and east of the country and warmer-than-average sea and air temperatures.

“Large-scale climate drivers (like La Niña) have elevated the risks of [a tropical cyclone] happening this summer,” said Dr Luke Harrington, a senior lecturer in climate change at the University of Waikato.

“In fact, seasonal predictions pointed to elevated chances of multiple [tropical cyclones] occurring in this region of the Pacific as early as October.”

Climate change cannot be blamed for Gabrielle’s existence – recent studies have suggested the globe’s warming is actually reducing the frequency of tropical storms in the Pacific – but the extra energy it affords systems could be making those that do form stronger.

“It’s likely that the low pressure centre of the system will be slightly more extreme than what might have been in a world without climate change, with the associated winds therefore likely also slightly stronger,” said Harrington.

Photo: RNZ / Mick Hall

Not many cyclones make it this far south intact, but the combined effects of climate change and La Niña are helping there too.

“The waters in the Tasman Sea and around New Zealand have been unusually warm,” said Dr Joao de Souza, director of the Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment-funded Moana Project.

“The rate of warming has been above the global average since 2012-2013, with the last two years presenting record-breaking ocean temperatures leading to unprecedented marine heat waves around Aotearoa.”

The current La Niña has been “protracted”, the World Meteorological Organisation said in August, and it is only just now starting to ease, after three Southern Hemisphere summers – the longest this century.

As a result, Stone said extreme weather systems like Gabrielle “can maintain themselves much closer to us than before and are not disrupted so much by cooler seas that are no longer there”.

“La Niña events also change the winds, bringing more hot and wet air from the tropics our way.

“Finally, the warmer air of a warming world can hold all of that moisture until it meets the mountains of Aotearoa.”

More to come?

And there could be more like Gabrielle on the way, sooner than you might expect.

“As the storm passes over New Zealand we see the ocean surface temperatures decrease as a consequence of the energy being drawn and surface waters being mixed with deeper, cooler waters. This is happening right now with Cyclone Gabrielle,” de Souza said.

“Once the cyclone moves away we should see the ocean surface temperatures rise again… All this means we have the pre-conditions necessary for the generation of new storms in the Coral Sea and their impact on New Zealand. And this situation is forecasted to prevail at least until April-May.”

The Coral Sea is a region of the Pacific between Queensland, the Solomons and New Caledonia.

The longer-term remains unclear, said Stone.

“Is Gabrielle’s track toward us a fluke… or does it portend the future? We do not really know at the moment, but NIWA, the MBIE Endeavour Whakahura project, and colleagues in Australia are developing techniques that we hope will help us answer that question very soon.”

* Information for this story was provided by the Science Media Centre

Discussion about this post