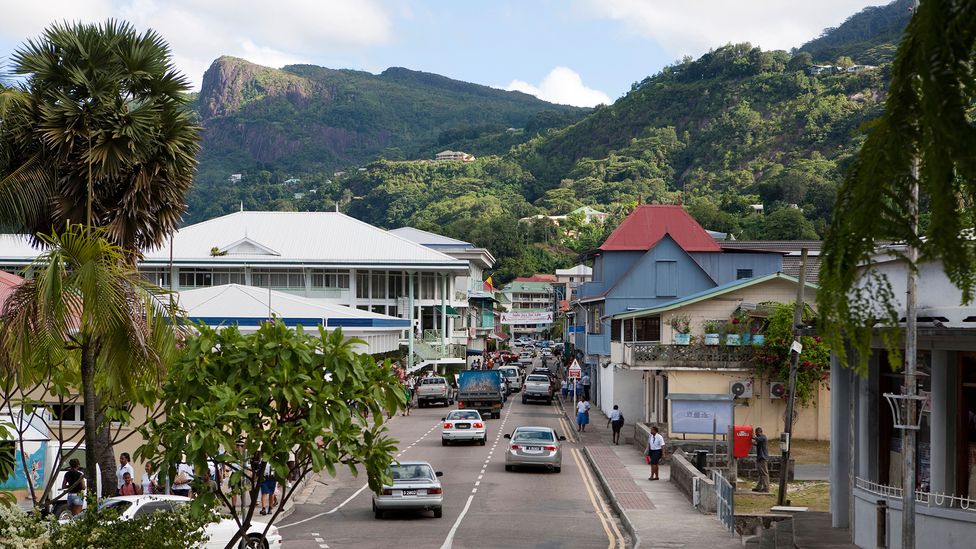

One of the world’s smallest capital cities

(Image credit: seychelles view/Alamy Stock Photo)

Built on land reclaimed from the sea, Seychelles’ tiny capital city can’t get any bigger – but with a vibrant culture and fascinating history, it doesn’t need to.

O

One minute I was out over a seemingly endless ocean en route to Seychelles. The next, dark granite cliffs filled the plane’s window, swirling in and out of the clouds with all the dark mystery of ships lost at sea. I became convinced that the plane was about to land on the water or crash into a mountain, so little space did there seem to be between the two.

The Seychelles is an archipelago of 115 islands, a sublime meeting of sea and land beneath a sky of impossible blues. Everything here, from the towering volcanic spine on the largest island of Mahé to the 1,800 kilometres of ocean that separate Mahé from mainland Africa, seems to happen on a grand scale.

Everything, that is, except Victoria, Seychelles’ tiny capital city.

There are other capitals around the world with smaller populations: San Marino or Vatican City, for example; or a handful of tiny Pacific Island cities. Even so, Victoria’s population of around 30,000 is modest by the standards of most seats of national power.

With a population of around 30,000, Victoria is relatively small for a capital city (Credit: imageBROKER/Alamy Stock Photo)

If there seems to be little space along Mahé’s narrow coastal strip for an international airport, there’s equally little room for a capital city. Mahé measures just 20 sq km; it would take barely 10 minutes to walk around the perimeter of the centre’s tight grid of streets. Houses climb the surrounding hills until the terrain becomes too steep.

That Victoria could even make it to this size owes much to past geographical engineering.

“Half of Victoria is reclaimed land,” said George Camille, one of Seychelles’ best-known artists who was born in Victoria and has spent much of his life here. “The sea was where the taxi stand now is.”

For such a small city, Victoria does a good job of telling the story of modern Seychelles through its buildings and its tightly concentrated clamour. It is an antidote to the popular Seychelles image of beaches and palm trees and a life far from the world and its noise.

Busy, urban Victoria shows visitors another side of Seychelles (Credit: imageBROKER/Alamy Stock Photo)

Victoria has surprisingly deep roots in its narrow plot of soil. The French founded the city in 1778, a time when the American Revolutionary War was raging, the penal colony of Australia was still just an idea and much of Africa remained untouched by Europeans. The new settlement – which was by all accounts a modest place of timber-and-granite houses, an army barracks and pens for keeping tortoises – was named, rather more grandly, L’Établissement du Roi (“the King’s establishment”).

Little was done to grow the new city, either by the French who first built it or the British who took it over in 1811. It was a harbour, a port, a convenient waystation en route to elsewhere. So small and unimportant was it that it took the British 30 years to change the name to Victoria; they did so in 1841 to commemorate the queen’s royal marriage to Prince Albert.

Its history was, for the most part, a minor affair for much of the 19th Century. After heavy rains, an avalanche of mud and granite rained down upon the city on 12 October 1862; many were killed. In 1890, the Swiss-owned Hotel Equateur opened, a precursor to the deluge of tourist business that would one day come to define Seychelles.

Women stop for a chat in front of an image of Lieutenant Charles Routier de Romainville, founder of the city of Victoria (Credit: Hemis/Alamy Stock Photo)

Perhaps the oldest extant building in Victoria is now, appropriately, the National Museum of History. With its engaging mix of written information panels and wall-to-ceiling displays, it tells the story of earliest colonial times, the freeing of slaves and the resulting history of Creole culture. Many established histories of the city speak of Victoria’s (and Seychelles’) colonial history, understandably so as it was the French and the British who would leave behind the architectural landmarks. But on 1 February 1835, 6,521 slaves were set free on Seychelles. The entire population at the time was just 7,500; nearly 90% of these were freed slaves and they would become the foundation upon which a Creole nation was established.

Originally built in 1885, formerly the building of the Supreme Court of Seychelles, the museum was restored in 2018 and remains a light and airy structure of wooden shutters and soaring ceilings surrounded by a palm-filled garden. It occupies the corner of Independence Avenue and Francis Rachel Street.

In the heart of this intersection and visible from the museum grounds is one of Victoria’s more curious monuments: a miniature replica of the clocktower known as Little Ben that stands on Vauxhall Bridge Road in London. It was brought to Victoria in 1903 and serves as a suitably diminutive signpost for a city that can never grow any bigger.

Shoppers queue at the Sir Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke Market (Credit: economic images/Alamy Stock Photo)

Inside the closely packed streets and lanes that comprise Victoria’s true centre, the “city” is a tight tangle of cars and people, horns and bright fabrics. Around the covered Sir Selwyn Selwyn-Clarke Market, the city becomes a mix of shouting fishmongers and fresh produce that ranges from coconuts and plantains to vanilla pods and chillies. Along Albert Street, old-school wooden trading warehouses in fading pastels share street frontage with a glass-walled casino. Nearby, there’s the extravagant balconied facade of the Domus (a residence for the church hierarchy, built in 1934). Over on Quincy Street, the Hindu Sri Navasakthi Vinyagar Temple rises amid the modern buildings.

Victoria’s Hindu Sri Navasakthi Vinyagar Temple rises from the city (Credit: mauritius images GmbH/Alamy Stock Photo)

“People think Seychelles is all about beaches,” said Connie Patel, local trader, amateur historian and lifelong Victorian. “And, of course, the beaches are important. But everything from Seychelles is here. There aren’t many roads here on Mahé; nearly all of them pass through Victoria. If you want to see where ordinary Seychellois come to do business away from tourism, Victoria is where it happens. It’s an essential part of the Seychelles story.”

Resident Geetika Patel, agreed: “Victoria is a window on the real Seychelles. It can be loud and messy and we all complain about the traffic. But this is modern Seychelles. Look around you. It’s a melting pot of faces and architecture that tells you a lot about who we are. Listen, and you’ll hear everyone talking in Creole. You can’t say you understand Seychelles unless you’ve been here.”

Up the hill, above the city and off Revolution Avenue, Marie-Antoinette Restaurant occupies an old home where, in the 1870s, Welsh-American journalist and explorer Henry Morton Stanley stayed for a month on his way back from Africa and his celebrated encounter with Dr David Livingstone. Stanley had been sent by a US newspaper to find Livingstone, who had lost contact with the outside world years earlier; it was at their first meeting on this trip that Stanley uttered the now-famous words, “Dr Livingstone, I presume?”. Upon his arrival in Seychelles on his way home, Stanley missed a French postal ship by a day and was marooned in Seychelles for a month while he waited for passage back to Europe. Built entirely of wood, sporting towers and turrets, the building is yet another signpost to a little-known past.

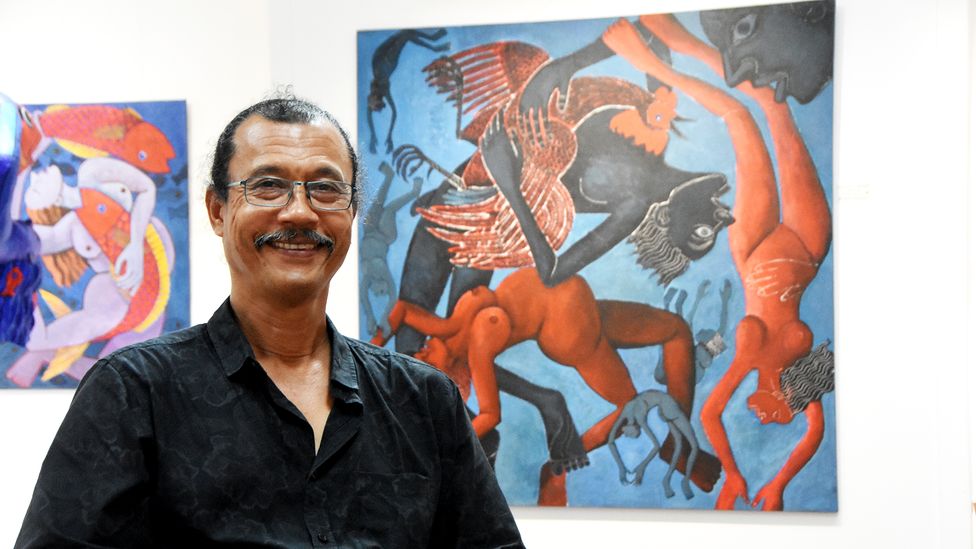

George Camille, one of Victoria’s best-known artists, wants to turn Victoria into a capital of Creole culture (Credit: Anthony Ham)

Just down the hill, artist Camille, who dreams of turning Victoria into a regional capital of Creole culture, has restored a traditional home built of casuarina, mahogany and other hardwoods, turning it into an exhibition space and art gallery known as Kaz Zanana for his confronting artworks. “This is what the houses of Victoria once looked like,” said Camille. “It’s a relic of a disappearing world.”

It was dusk as I left Kaz Zanana and wandered down into the city centre. Lost in thought, I found myself outside the market. The day’s heat had gone, as had the market traders. There was no traffic. The streets had fallen silent. In that moment, Victoria felt, perhaps, like the village it once was, and never really outgrew.

—

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Discussion about this post