Luis went to prison on a life sentence 16 years ago, at age 17. Food came on a tray and leftovers were removed on the same brown plastic rectangle.

So he had never cooked or done dishes before moving to the “Little Scandinavia” unit in the Pennsylvania State Correctional Institution at Chester last year — an experiment modeled after Northern European systems of incarceration, where the goal is less about punishment and more about turning out people who can be good neighbors.

Here, Luis (Pennsylvania prison rules prevent me from using his last name) has use of four stainless steel stoves, two blond-wood islands, pots including a bright blue Dutch oven and a fridge that holds groceries from a nearby supermarket. There are even some not-too-sharp knives.

“It dawned on me that all these years I had become conditioned and dependent,” he told me, standing in that spotless kitchen shared by 54 men. Being able to clean up after himself was an autonomy he didn’t even know he wanted, or needed.

The kitchen in the “Little Scandinavia” unit is spotless and stocked with an array of appliances, cooking utensils and fresh groceries.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

This week, Gov. Gavin Newsom will announce that California will take its own leap forward, rethinking the purpose of prison by “ending San Quentin as we know it,” he told me Wednesday.

By 2025, California’s first and most infamous penitentiary, where criminals including Charles Manson and Scott Peterson have done time, will become something entirely different: the largest center of rehabilitation, education and training in the California prison system, and maybe the nation. No longer will it be a maximum security facility. Instead, it will be a place for turning out good neighbors, incorporating Scandinavian methods.

The vision for a new San Quentin includes job training for careers that can pay six figures, trades such as plumbers, electricians or truck drivers, and using the complex as a last stop of incarceration before release. Tucked in the proposed budget Newsom released weeks ago is $20 million to jump-start the effort.

The plan for San Quentin is “not just about reform, but about innovation,” a chance to “hold ourselves to a higher level of ambition and look to completely reimagine what prison means,” Newsom said.

The “Little Scandinavia” unit features comfortable, open living spaces meant to encourage conversation and connection.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

Along with Pennsylvania, the Scandinavian philosophy of incarceration has already been implemented in pilot programs in Oregon and ultra-red North Dakota, as well as in small-scale experiments inside a few other California prisons.

But what’s envisioned for San Quentin is on a different scale. The choice of this prison, tucked on a peninsula in wealthy Marin County and overlooking San Francisco Bay, is a statement by Newsom about justice reform and about California — one with the potential not only to change what it means to serve time, but also to create a pathway to safer communities that our current system has failed to deliver.

Despite consent decrees, prison closures and even the de facto end of the death penalty, California’s approach to crime and punishment remains problematic, as it does across the U.S. Our recidivism rates remain stubbornly high, people of color are disproportionately incarcerated, and both conservatives and liberals make loud arguments as to why.

The goal of the Scandinavian approach to incarceration is less about punishment and more about turning out people who can be good neighbors.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

Fundamentally, we can’t agree on what prison is for — should its main goal be to punish, or guide? To be a source of ongoing suffering, or opportunity?

Many on the right say prison should serve as a deterrent: Serving time is not supposed to be pleasant, and hard conditions teach hard lessons. On the left, many say restorative justice and other means of diverting people from incarceration should be the priority.

But do such dichotomies miss the point?

The reality is that most people who go into prison come out again, more than 30,000 a year in California, Newsom points out. So public safety depends on people choosing to change, and having opportunities for a sustainable, law-abiding life. Otherwise they will simply go back to what they know, be it selling dope, robbing houses or worse.

“Do you want them coming back with humanity and some normalcy, or do you want them coming back more bitter and more beaten down?” Newsom asks.

The Scandinavian model looks at the loss of liberty and separation from community as the punishment. During that separation, life should be as normal as possible so that people can learn to make better choices without being preoccupied by fear and violence.

Gina Clark, superintendent of the Pennsylvania State Correctional Institution in Chester, is still gauging the success of “Little Scandinavia.” Her aim is to turn out inmates who will help rather than hurt their communities.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

Influencing people to make those better choices, “should be the common goal, no matter what your opinions are, where your beliefs are, what political party you are affiliated with,” Gina Clark, the superintendent of Chester (the Pennsylvania equivalent of a warden) told me.

Clark inherited Little Scandinavia from her predecessor and is waiting for more data before deciding if it works. But incarceration’s purpose, she said, should always look beyond the offender to the community. Will this person help or hurt their community when released? Have we done everything we can to ensure it is the former?

That focus on community safety could make the Scandinavian model the sweet spot of consensus — if people can get past the politics and understand what Chester and now San Quentin are trying to do. And that comes down to understanding the officers who spend their days on the front lines of incarceration.

::

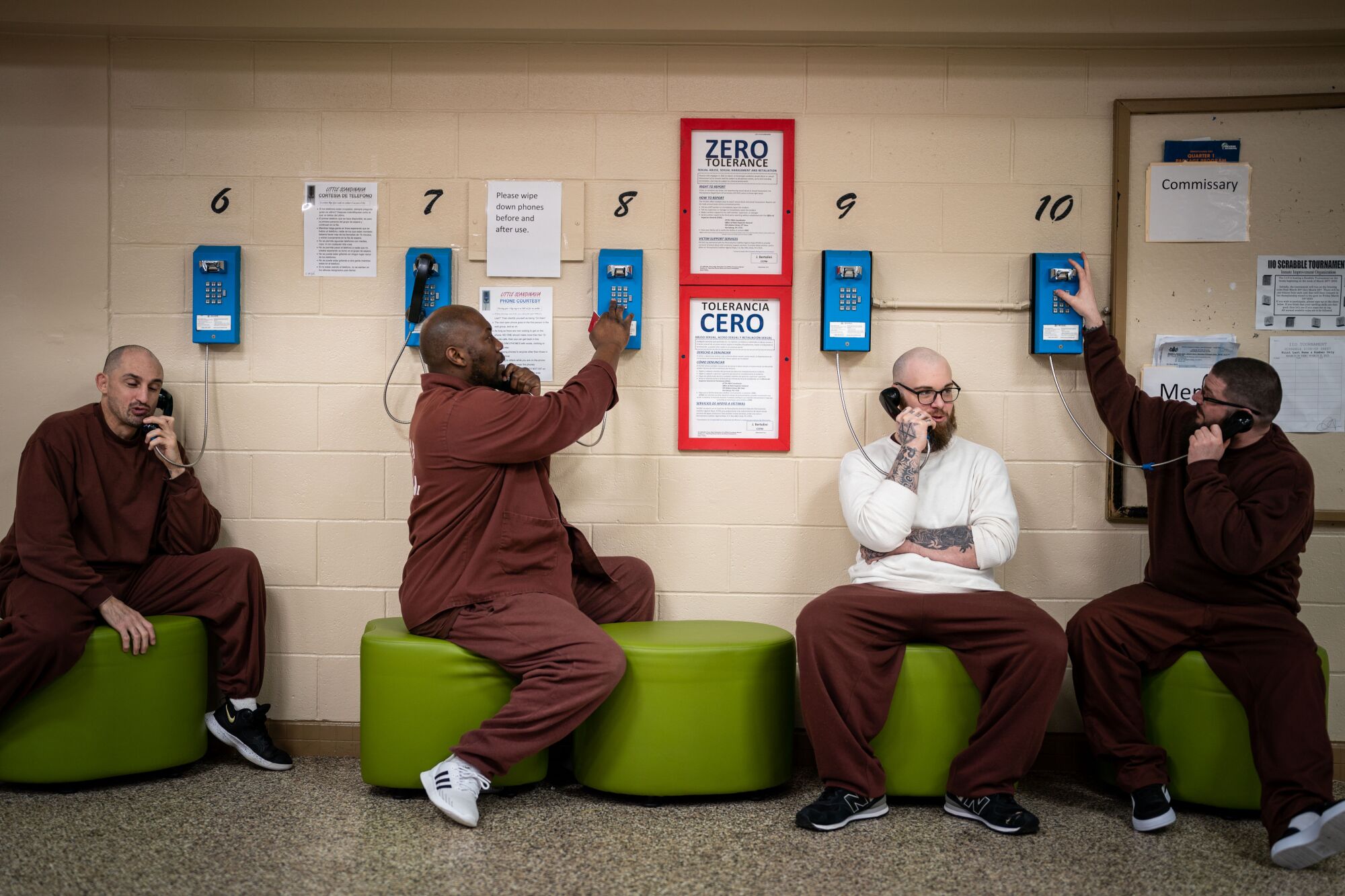

The Scandinavian prison model encourages collegiality on the theory that inmates can learn to make better choices when they are not preoccupied by fear and violence.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

Pennsylvania corrections officer Matt Tompkins has the word “sink” tattooed below the knuckles of one hand and “swim” on the other.

It’s a nod, he said, to lyrics from an old punk song. But for a while it was also how he felt about his job inside Chester, in the same gritty area outside Philadelphia where he was born. Stress and confrontation were constant and he felt like he was sinking. Just like the men he was watching.

“It wears you down,” he told me. “Little by little, over the years.”

Prison guards have high rates of depression and health issues. Studies have shown they face a risk of suicide 39 times higher than for people in all other professions. Tompkins has lost two colleagues that way in seven years.

But his outlook changed in 2019 when Chester began planning Little Scandinavia. A professor from nearby Drexel University, Jordan Hyatt, conceived of the experiment with a European colleague and helped arrange a trip to Norway, Sweden and Denmark, where Tompkins was able to work with his counterparts.

Experts familiar with the Scandinavian prison model say that when correctional officers and inmates break down the “us vs. them” wall, prisons are better places for everyone involved.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

It was “mind-blowing,” Tompkins said. A European officer asked him what a good day looked like, and Tompkins’ answer was that American standard of law enforcement: when he went home to his family alive.

“Like I don’t get stabbed, I don’t get beat up, I don’t get hurt,” Tompkins said.

That shocked the Scandinavian officer, who saw a good day as one where he changed an inmate’s life for the better.

“I never once thought, as a correctional officer, I had the ability to change somebody’s life. Never dawned on me whatsoever,” Tompkins said. “And that’s when a lightbulb went off in my head. … You recognize that when you have the ability to help someone, it feels good.”

Though Tompkins once dreamed of jumping to the FBI, he now thinks he could retire from Chester. He is so confident of his safety that on the day I interviewed him, he had left his pepper spray in his office.

Shower facilities in the “Little Scandinavia” unit are clean and offer inmates some privacy.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

In his unit, the officers aren’t saddled by rules against fraternizing with prisoners. Instead, they are trained as mentors and assigned a handful of men for whom they serve as the main contact for getting help, whether that be a personal issue, educational resources or a friendly ear. Sometimes they sit down on the blue couches and just talk.

“I still deal with a lot of individuals with different personalities, different problems, different complexes, and it can be emotionally draining,” Tompkins said. “But that trade-off is a lot easier when you realize you can make a difference.”

Building those relationships leads to “dynamic security,” Hyatt, the researcher, told me — a peace held not through force but through mutual respect and a willingness to hear what the inmates need and want.

Before you roll your eyes, it’s not just Hyatt and Tompkins who say it works. In more than a dozen interviews I did with experts, officers, inmates and former inmates, there was consensus that when guards and incarcerated people break down the us-against-them wall, prisons are better places for everyone involved.

“We are 100% behind the Norway project when it’s done right,” Glen Stailey told me. He’s the head of the California Correctional Peace Officers Assn., the union that represents guards.

Inmates in the “Little Scandinavia” unit are able to order fresh groceries and cook their own meals.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

Sam Lewis, the executive director of the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, an advocacy organization working to end mass incarceration, told me much the same thing.

“The prisons that we have in America were not meant to transform people into the best versions of themselves. They were built to house and warehouse people,” said Lewis, who himself served 24 years. But the Scandinavian model is “helping people become the best version of themselves. As we bring people home, if we give them real opportunities to make a decent living, think of how we are breaking the cycle.”

Lewis and Stailey traveled to Norway and Sweden in 2019 and were stunned by the way officers and inmates interacted. They saw the potential despite the differences between the U.S. and Scandinavian countries. Officers “value the relationships they build with people in prison, so they value the people in prison,” Lewis said.

That shift, prioritizing care over control, is the heart of what San Quentin is about to do. But it’s the “when it’s done right” part that both Lewis and Stailey worry about.

The entrance to the “Little Scandinavia” unit greets visitors with colorful murals.

(Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times)

California is not Norway — gangs, drugs and mental illness plague our system to a degree unimaginable to our Scandinavian counterparts. All of those problems will need to be accounted for, along with convincing correctional officers that less aggression actually makes them safer. San Quentin will need to train officers and give them the space to use that training, meaning more officers for fewer inmates.

But most of all, success will require a cultural shift inside and outside the walls of San Quentin, a belief that those coming out of prison deserve to be our neighbors.

Luis, originally convicted of first degree murder, was recently resentenced due to a change in laws for juvenile offenders. He may be eligible for parole in five years. He credits Little Scandinavia with giving him a chance of success on the outside by offering him the dignity, calm and opportunity to figure himself out.

He no longer sees the way he grew up as normal, no longer looks at violence and crime as inevitable. Now, he thinks about being closer to the son he had when he was 14. Maybe he’ll make him dinner, saute him some shrimp if he gets the chance.

“As humans, we adjust. So if the environment is bad, eventually you start to drift,” he said of regular prison. “Here, it’s productive. So by the time you get out, you’re a better person.”

And that’s a triple win — for Luis, for the officers who watch him today, and for the neighbors he will one day have.

Discussion about this post