Kachou Fuugetsu (literally: Flower, Bird, Wind, Moon) is a Japanese concept meaning to discover yourself while experiencing nature. In Japan, there are few better places to do so than on the slopes of Fuji-San

There’s a mere three-month window for hiking Mount Fuji, Japan’s 3 776m-high extinct volcano, and my wife Catherine and I were determined to reach the summit.

We’d only a few hours in Tokyo before boarding our bullet train but that time had opened our eyes to the fact that we were now in a place so different from anything we’d seen before.

Everything was just so… foreign. From the orderly queuing for the trains, to the green tea-flavoured Haagen Dazs. And, in one corner cafe – right next to the vegetables – were creatures swimming in brine that I could not identify, let alone imagine eating with chopsticks.

We’d read about climbing Fuji-San online and knew that the only way to do it “properly” was to hike up overnight, summiting just before dawn to watch as the sun peeked through the clouds while samurai warriors danced on red-and-white rainbows.

Admittedly, we’d done minimal planning. Maybe read a few first-hand accounts. But we were relatively fit and fearless 20-somethings and we were catching a bus to Station 5, cutting out some 2 300m of lower-slope slog. All in all, we reckoned, there were just five more stations – confusingly labelled 6, 7, 8, 8.5 and 9 – and a mere 1 500 more metres to climb.

Would it be tough? Almost certainly. But the Japanese have a saying: Nana korobi, ya oki (fall seven times, rise eight times). That saying was written for Catherine and me.

We started at 10pm and made our way through a little forest. The little torch we’d purchased earlier came in handy during the first few hours when we found ourselves utterly alone for the first part of the hike.

Things weren’t as simple as we’d imagined. For one thing, the trail’s surface consisted of millions of little volcanic stones that slid over each other so that each step resulted in a little slide backwards. It may be a cliché to say “two steps forwards, one step back”, but that was precisely the case. There were chains and pegs in the ground to help us and patches of snow as we zigzagged our way up the mountain.

It was getting colder, too. Good thing we brought gloves. Weren’t we clever? Sadly no warm beanies for our heads, but we’d be okay, right?

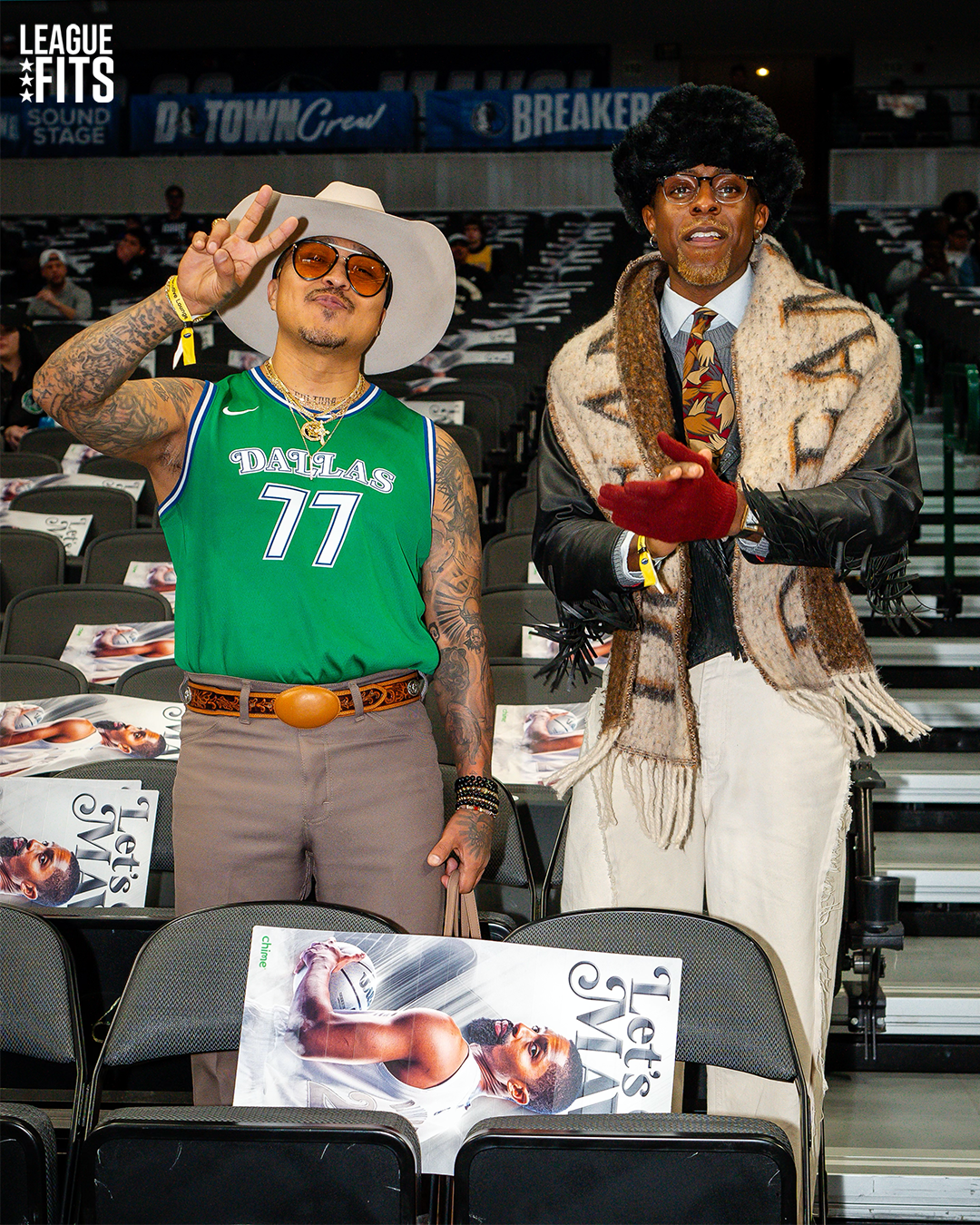

Illustration: Jess Nicholson

After three or four hours, we began to pass other climbers, folks who’d wisely bought spots in overnight huts where they could break their climb into manageable chunks, acclimatising comfortably in the process.

We had no such luxury. We were shattered, losing our breath often now. We would stop every few minutes, regain our breath and our will to carry on, and set off again. Except that didn’t get us very far: four steps, maybe five, and we were exhausted once more. It wasn’t only our lungs that were finished. Because the mountain was so steep, we had to really lean into it, which meant we were frequently off-balance, stumbling over our own feet.

And now it was getting really cold.

After another hour or so we reached the 8th station and we knew we must be getting pretty close, not that we could see anything above. It was around this time that I began to feel sick and after a bit more hiking, vomited.

You, dear reader, may put two and two together and say … ah, altitude sickness, of course. We, however, did not.

It simply hadn’t entered our minds that what we were doing was dangerous. It was tough, perhaps. But, being South Africans, our instinct was to push through. After all, as the Japanese say: Keizoku wa chikara nari. Continuing on is power.

As we got higher, the icy wind strengthened. I tied my rugby jersey around my head to stop my ears from freezing. Whenever we stopped, though, we’d get headaches – uncomfortable rather than painful ones – and so we simply stopped less, and walked slower instead.

At 3.50am we started to see light on the horizon and mild fear set in – slight panic that we wouldn’t summit in time. Mercifully, when we rounded the next bend we saw a large torii, a symbolic gate marking the top. We’d walked for six hours and had 20 minutes to spare before the sun was due. We were elated.

Our joy was short-lived. The wind was now gale-force and there wasn’t much shelter at the top. There was a (locked) hut though, so all 20-odd people up there cuddled close as we sheltered from the wind, awaiting the sunrise.

The sun slivered into sight – right on time at 4:22 – and there were a few shouts of “Banzai!” from the crowd around us. It was beautiful, yes, but it was too cold for us to think about celebrating. We were uncomfortably cold, chilled to the bone and thinking only about our descent.

But we hadn’t yet actually peered into the volcano. Doing so meant walking up another path – just 50 metres – to reach another viewing spot from where we could finally look down into the crater.

We were reluctant to traipse out onto that final bit of pathway, completely exposed to a frigid wind that seemed to be blowing in directly from the North Pole.

FOMO being what it is, though, we couldn’t not go up to see what all the fuss was about.

Out in the open, that gale brought with it ice and sleet that hammered every inch of exposed flesh, frozen needles stabbing our faces as we headed up to the viewing spot. There, we peered down into the crater for a moment, looked at each other, and within seconds were sprinting back down to the hut.

We had done it. We’d conquered Fuji, we’d stared into the eye of the beast…

Ame futte ji katamaru, rained-on ground, hardens. Or, as we discovered, adversity builds character.

This article originally appeared in the June 2022 print issue of Getaway

Words: Alan Valkenburg

Illustration: Jess Nicholson

Discussion about this post