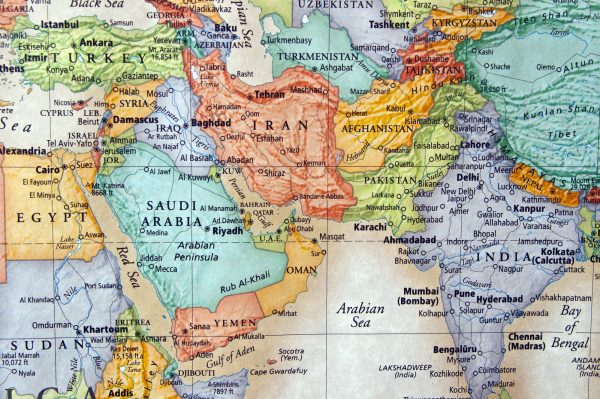

Much has been written about the potential of the International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC) as a geopolitical game changer and, at least among some Indian commentators, a better and fairer alternative to the China-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). INSTC would run from Russia through the Caspian Sea, with a stop in Azerbaijan, then on to Iran and, via the Arabian Sea, India. Notwithstanding the ambitions, little progress has been made on the completion of the various rail and road projects associated with this mammoth trade route.

Still, India’s refusal to fully comply with Western-led sanction regimes against Russia, New Delhi’s skepticism toward the use of sanctions as policy tool, and the recently signed rail cooperation agreement between Iran and Russia as well as the ongoing free trade agreement negotiations between India and Russia have, collectively, reignited enthusiasm amongst commentators and analysts about the prospect of INSTC as a viable alternative to both Chinese and Western dominated trading routes between Eurasia and flourishing South and Southeast Asian markets.

The rationale for operationalization of INSTC is, at least for the three major players in it, straightforward. As an extended version of the Persian Corridor, INSTC would provide India, Iran, and Russia with a shorter trading route while also presenting them with optionality. In the case of India, it would allow New Delhi to bypass Pakistan and gain access to the markets of Central Asia, where Chinese corporations are fast consolidating their presence. For Iran and Russia, on the other hand, INSTC enables them to better shield, if not immunize, themselves from Western-led sanctions, catalyze economic growth, and accelerate their move towards de-dollarization.

Yet, the trio’s vastly varied threat perceptions and strategic interests and/or priorities, not to mention their limited financial resources, will most likely hinder their cooperation on the completion of INSTC.

First and foremost is the question of China and their differing views on Beijing. While India attaches importance to INSTC as an alternative to China’s BRI and views Beijing as a strategic competitor, Tehran and Moscow have a much more sanguine perception of China. As such, and given the Iran and Russia’s increased isolation on the global stage, neither is likely to support, let alone participate, in an endeavor that would aim at clipping China’s growing strategic wings.

Although Russia shares some of India’s anxieties regarding China’s fast growing influence in Central Asia, Moscow does not, and in an important sense cannot, afford to treat Beijing as a strategic competitor. Given its isolation on the world stage and its dire economic situation, Russia is not in a position to antagonize China, and thus it will refrain from participating in projects that aim at curtailing China’s growing strategic presence.

Iran, similarly, is likely to be wary of turning INSTC into an alternative to China’s BRI, not least because it has signed a long-term strategic agreement with Beijing. India’s compliance with the U.S.-led sanctions since 2017, its patchy commitment to the Chabahar Free Trade zone project, and its fast growing ties with Israel have led to a downgrading of India’s trustworthiness in the eyes of Iranian policymakers. This demotion was evident in the nullification of Indian companies’ contract for the Chabahar-Zahedan railway as well as their disqualification from the bidding process for the development of Farzad B gas. As Beijing and Tehran expand their diplomatic cooperation to include joint regional initiatives and deepen their defense and security ties, Tehran will be reluctant to partake in any effort that would jeopardize China’s strategic interests.

Equally significant is India’s own evolving strategic orientation. Its push for the operationalization of INSTC can be perceived, in some corners, as an anti-Western endeavor aimed at empowering two of the West’s major foes: Iran and Russia. As the hype of India’s growing strategic clout begins to ring louder, today, more than ever before, India needs to be realistic about its position and weight in international politics; that is, while it is on course to become a great power, it is still far from that status.

Strategically, insistence on INSTC and a free trade agreement with Russia could weaken India’s standing in the Indo-Pacific and cost it its Quad membership. While it is true that the United States’ desire to lure India closer to its orbit places India in a strong bargaining position, Indian officials need to be cautious not to overplay their hand. Economically, Prime Minster Narendra Modi’s vision of turning India into a major technological power is tightly hinged to its ability to access, attract, and retain Western technologies and technological companies. Any push for initiatives that could be seen as detrimental to Western interests, however, could, directly and indirectly, jeopardize the materialization of that vision. India’s defense modernization program, to take another example, could receive a major boost from closer cooperation with Western contractors provided that the Indian government can take advantage of the current desire in Western capitals to entice New Delhi from Moscow by expanding the scope of their defense ties with India

For INSTC to have any realistic chance of ever becoming a fully fledged trading route, it needs to accrue benefits to not just the three core states but also some, if not all, of India’s democratic allies. For that to happen, India first needs to devise a way to end the ongoing war in Ukraine and hope for a softening of domestic political outlook in Iran, whereby, to rephrase Henry Kissinger, Tehran starts to act as a nation not a cause.

Discussion about this post