By Roxanne Reid

‘There!’ His voice is a loud whisper intense with excitement. We follow his pointed finger, peering intently through the tree branches. Nothing. He starts to explain and we trace the trunk of the tree, the branch jutting out … and then suddenly there’s a flash of brown wings and it’s gone again. We’re birding in the Okavango Delta, Botswana, and this is something special.

Luckily, our guide has followed the bird’s movement. He coaxes us till we find the Pel’s fishing owl with our binos, a blur of feathers behind a branch. It’s a secretive bird and therefore a much sought-after tick for birders. We consider ourselves lucky to have caught even a glimpse; it’s only the second time in our lives that we’ve seen one.

The ginger-brown Pel’s is rare, with fewer than 500 pairs in southern Africa. Here in the Okavango, though, it occurs in good numbers, lured by the Delta’s pristine waters, its quiet channels and lagoons. But it was still a coup; we later met a man who had given up all game drives for two days just to go in search of a Pel’s – without success.

As we set out on the water channels early the next morning, our guide suggested we look again for the Pel’s. He cut the motorboat’s engine about 15 metres away and started quietly pushing it forward through the reeds with a long wooden pole, as if it were a mokoro.

Pel’s is a nocturnal hunter of fish, frogs, crabs and even baby crocs, but it usually spends the day roosting in a shady tree, keeping a low profile. That’s why it’s so easy to miss. Luckily, our guide knew where and how to look, so we got a second chance. This time the owl posed for a few photos (hey, they may not be prize winning shots, but at least we saw it!). Then it flew to another tree and we decided to leave it in peace.

Bateleurs to bee-eaters

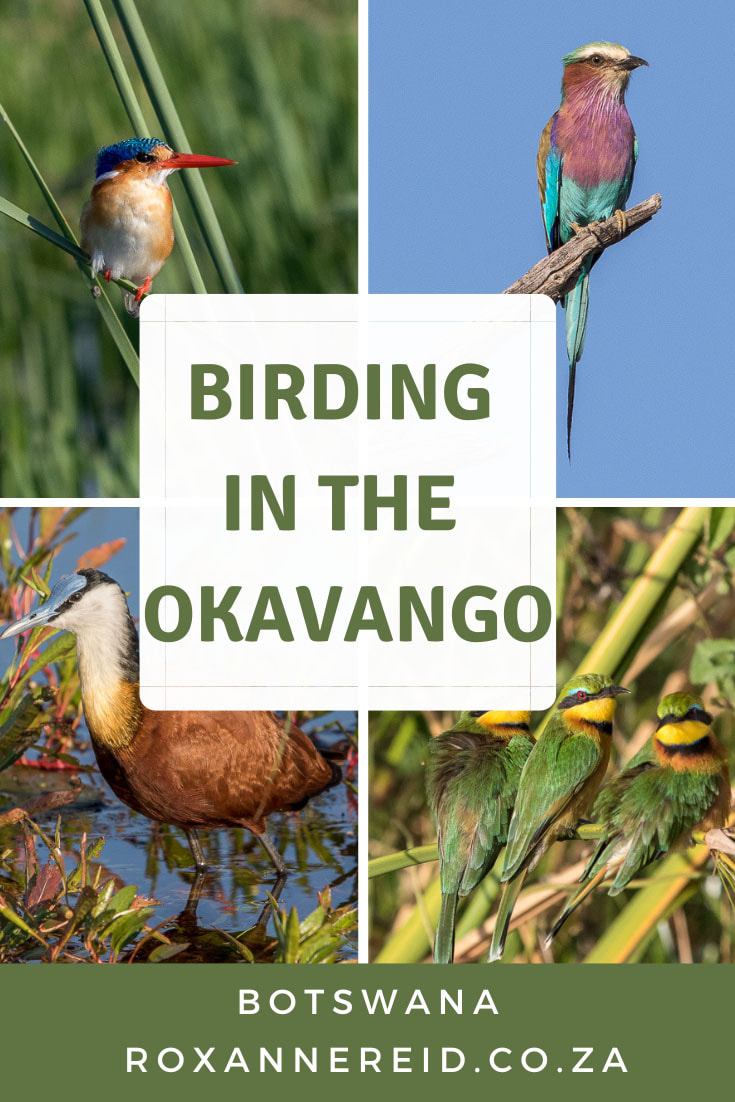

Of course the Pel’s was a highlight of our time in the Okavango Delta. But there were bucket-loads of other birds too, from bateleurs, darters, green-backed and goliath herons to little bee-eaters, pied kingfishers and a malachite kingfisher swaying on a reed in the breeze, its bright red beak so long it looked as though the bird might overbalance and fall on its face.

There were loads of African jacanas too, surfing among the water lilies on the wave created by our boat. Mother jacana is unusually sneaky: she’ll lay the small, brownish eggs with fine dark ‘crack’ lines all over them and then high-tail it out of there in search of another male to mate with.

If words like rufous-bellied heron, greater swamp-warbler and coppery-tailed coucal send a shiver of excitement through your veins, the Okavango will rock your socks.

The Okavango Delta

The Okavango Delta is vast area of some 16 000 square kilometres that swarms with life, including more than 1000 species of plants, nearly 500 bird species, and 130 mammal species, not to mention numerous species of reptiles, amphibians and fish. Each year, about 11 cubic kilometres of water spreads over the vast area so the watery landscapes and water lilies will thrill you too.

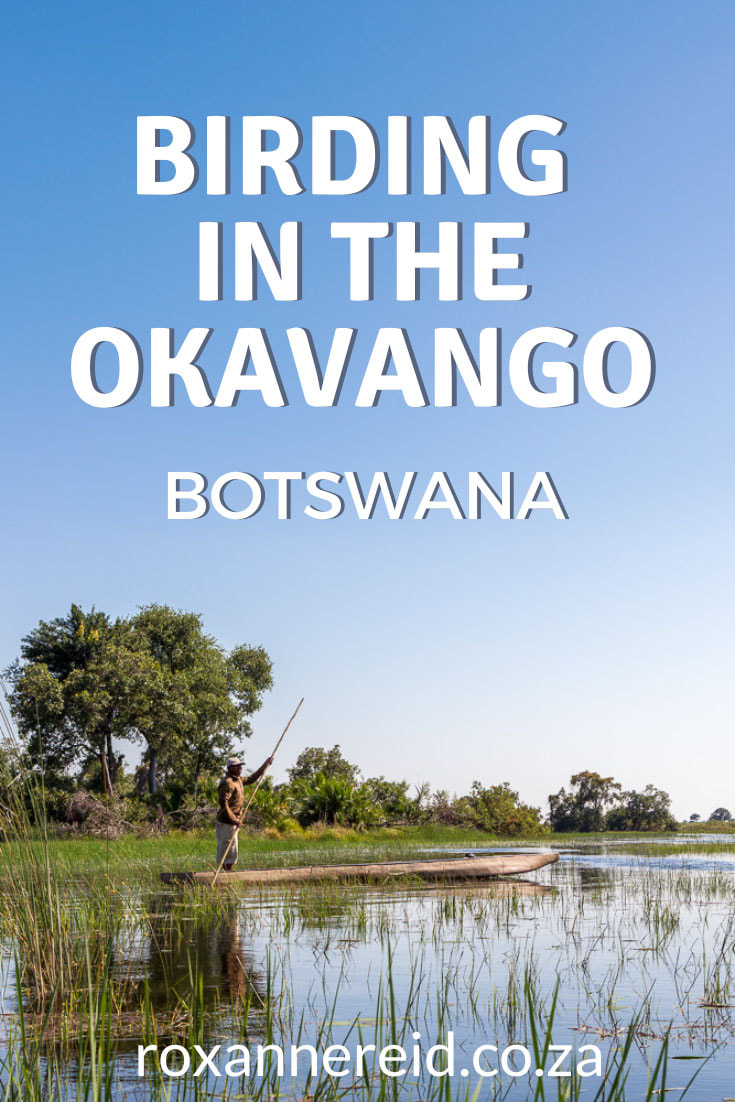

One of the best ways to see it all is from a mokoro, with a guide slowly and silently poling you along. You become part of nature so it’s an immersive way to see animals, especially birds and smaller creatures like frogs and dragonflies. These craft were traditionally made from wood, but Botswana’s efforts to prevent deforestation mean most of them are now made of fibreglass.

Botswana is not a budget destination, given that the government has chosen to opt for a high-value, low-impact model of tourism. Obviously, there are numerous wonderful high-end luxury camps in the Okavango Delta, such as those managed by Wilderness, Great Plains Conservation, Desert & Delta Safaris, and Sanctuary Retreats.

But for those who can’t afford such luxury – or the truly excellent guides they offer – your best way to enjoy the Okavango is to self-drive and camp in the Moremi Game Reserve or the Khwai Concession.For the best all-round affordable self-drive Okavango/Moremi experience I’d suggest two to three nights at each of the following: Third Bridge and Xakanaka in Moremi, and either Mbudi Campsite or Hippo Pool Campsite in the Khwai area.

It’s well worth splashing out for a mokoro trip too, either from the Mboma station near Third Bridge, or from Mbudi or Hippo Pool in Khwai. Xakanaka offers motorised boat trips instead. You can book for these at the reserve’s entrance gate or at the camp.

Usually, the dry season months of June/July to October are the best time to visit, although October can be very hot. These are the months when the rains have stopped but the floodwaters have already arrived from the highlands. This offers you the best combination of game drives on land as well as boat trips along the waterways.

That said, the Okavango can be considered a year-round destination if you’re not going to concentrate on water-based activities. Bear in mind too, that July to October is high season, when peak tariffs apply. If you’re looking to cut costs, going outside these months may be a more affordable option. Game viewing is still good in April/May and November/December, although November and December can be very hot. January to March are also hot and wet months when some areas of the Delta become inaccessible.

Although the Delta is good for birding all year round, the summer wet season from November to April is when summer migrants swell the number of bird species you might see. Bear in mind that the summer months of December to March are very hot and some areas become hard to get to, so April might be a good choice.

You may also enjoy

Best Botswana game reserves for a wildlife safari

Okavango, Botswana: where the mokoro is king

8 best things to do on safari in Botswana

Like it? Pin this image!

Discussion about this post