One week before he was killed in the death chamber at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, Donald Grant asked a woman named Sue Hosch a question about his coming execution. “He asked me, did I think it was going to be botched?” Hosch recalled. “And I said, ‘I don’t know.’” As an activist who corresponded with men on death row, Hosch hoped that Grant would die peacefully — “you know, go to sleep.” But he told her that he was scared.

Grant had good reason to be afraid. In his years on death row, he had seen neighbors taken to die whose executions had gone horribly wrong. Since 2014, Oklahoma’s three-drug lethal injection formula had relied upon midazolam, a sedative that experts warned was inadequate to provide anesthesia. In a lawsuit, attorneys for people on Oklahoma’s death row argued that using midazolam put their clients at risk of “severe pain, needless suffering, and a lingering death.” After a series of disastrous executions made national news, officials announced that they would revise the state’s methods. But when Oklahoma released a new protocol in early 2020, the lethal injection formula remained the same.

The litigation over the state’s death penalty culminated in a federal trial earlier this year to determine whether Oklahoma’s lethal injection protocol violated the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. By then, a series of Supreme Court rulings had created daunting new hurdles for people facing execution, including a requirement that Justice Sonia Sotomayor labeled “surreal.” Lawyers for the condemned could no longer simply challenge a state’s execution protocol. They also had to propose a “feasible and readily implemented” alternative by which their clients would prefer to die.

The Oklahoma plaintiffs outlined four alternative methods of execution, including the firing squad. But Grant and five others declined to choose one. U.S. District Judge Stephen Friot swiftly dismissed Grant and the other men from the lawsuit. Although the state had indicated that it would not seek execution dates until the litigation was resolved, Friot suggested in a footnote that if the attorney general were to request dates for these men, they might provide the court with a useful “track record” to assess midazolam. Prosecutors took the hint: In September 2021, Oklahoma set execution dates for all of them.

One thing was clear: Oklahoma’s protocol would almost certainly be declared constitutional.

The next month, the state carried out its first execution in six years. Witnesses described how John Grant (no relation to Donald) convulsed and vomited shortly after the execution began, then appeared to struggle for breath. One witness who had previously attended six executions testified that she’d never heard anyone gasp for air that way. “It appeared like he was choking on the vomit,” she said.

Prison officials insisted that such accounts were exaggerated. An internal report showed that Grant had consumed potato chips and soda just before his execution. This brought no comfort to Donald Grant, who was scheduled to die in January 2022. He worried that his execution might even be botched on purpose. Like many on death row, he had a history of mental illness, which could make him paranoid. “Sometimes he’s like, you know, ‘How did you get my number?’” Hosch said of their phone conversations. “And I have to remind him, ‘Donald, you asked for my number. You called me.’”

Grant was scheduled to die at 10 a.m. on January 27. It was an overcast, bitterly cold day in McAlester, Oklahoma. In a gray jacket and pink winter hat, Hosch waited for updates alongside a small group of activists and press. Grant’s family had traveled to Oklahoma to witness the execution. His oldest brother, Joe, had been incarcerated for years in New York, which no longer had the death penalty. “This has been weighing on him very heavily, that had Donald committed the same crime in New York, he would not be on death row,” Hosch said.

Around 10:20 a.m., videos of the Department of Corrections director appeared on Twitter. “The sentence of Donald Grant has been carried out,” he said. Afterward, Grant’s spiritual adviser, the Rev. Don Heath, came to join the remaining protesters outside the prison. In a low voice, he described Grant’s last moments. Grant had remained fearful until the end, Heath said. But “his passing was reasonably peaceful, as far as I can tell.”

There was no way to know what Grant experienced on the gurney. Whether his execution could offer any evidence to be used at the upcoming lethal injection trial remained to be seen. But one thing was clear: Oklahoma’s protocol would almost certainly be declared constitutional. After that, Heath said, “We’ll have … men being executed every three weeks for the next two years.”

Photo: Liliana Segura/The Intercept

Standards of Decency

For as long as the death penalty has existed in the United States, the Supreme Court has never invalidated a method of execution. Although it has reined in the punishment over time, the court has historically given legitimacy to even the cruelest ordeals. In 1947, the justices ruled in the case of a young Black man named Willie Francis, who had survived an execution attempt in Louisiana’s electric chair. A majority of the court found no violation of the Eighth Amendment, calling it “an innocent misadventure.”

Although today’s court claims to be guided by “evolving standards of decency” in its Eighth Amendment jurisprudence, this concept has not extended to the methods states use to kill. When the court decided Baze v. Rees, upholding Kentucky’s lethal injection protocol in 2008, Chief Justice John Roberts invoked the Francis case, writing that “an isolated mishap alone does not violate the Eighth Amendment, because such an event, while regrettable, does not suggest cruelty.”

Today the insistence that botched executions are “isolated mishaps” has become harder to defend. A year after Baze, Ohio tried and failed to kill Romell Broom, prodding him with needles for two hours in an unsuccessful attempt to place an IV. When Broom sought to stop the state from trying again, the Ohio Supreme Court rejected his appeal. Two more men have since survived lethal injection attempts under similar circumstances. Many more have been killed with IVs inserted into their groins. In states across the country, numerous condemned people have appeared to suffer on the gurney — gasping, writhing, and heaving, only for officials to declare that everything went according to plan.

But nowhere in recent memory have executions been more disastrous than in Oklahoma. John Grant’s death was only the latest in a history of botched lethal injections that made the state’s death penalty infamous — and set the stage for the trial in federal court. With additional executions scheduled before the trial would officially decide whether Oklahoma’s protocol was constitutional, it would have been logical to hold off for a ruling. But the state pushed forward anyway, killing Bigler Stouffer in December, Donald Grant in January, and Gilbert Postelle in February.

Against this twisted backdrop, the proceeding in Oklahoma City seemed preposterously rigged from the start. Nevertheless, over six days beginning in February at the William J. Holloway Jr. United States Courthouse, attorneys dutifully presented evidence that midazolam could not provide the necessary anesthesia to keep their clients from being tortured to death. They showed autopsy reports revealing evidence that executed men had suffered from acute pulmonary edema — the sudden collection of fluid in the lungs, which feels like drowning. And in accordance with the law, they proposed better ways for the state to kill their clients.

In the end, it wouldn’t matter. On June 6, Friot ruled just as everybody knew he would. The “Eighth Amendment, as construed and applied by the Supreme Court in its lethal injection cases, does not stand in the way of execution of these Oklahoma inmates,” he wrote. A few days later, the state attorney general requested execution dates for 25 more people on death row.

Oklahoma’s lethal injection trial will eventually be a footnote in the long road to insulating executions from legal challenge. As the state gears up its execution machinery, the responsibility lies not only with officials who have ignored Oklahoma’s gruesome record, but also with a Supreme Court that has aided and abetted state-sanctioned murder at every turn. Today the evidence is on the side of those who call executions torture, even if the law is not.

People walk past the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum in 2022.

Photo: Liliana Segura/The Intercept

Body on Fire

The federal courthouse in downtown Oklahoma City sits one block from where Timothy McVeigh set off a bomb that killed 168 people in 1995. The terrorist attack is commemorated at the nearby memorial and museum, where visitors can view footage, testimonials, and artifacts from the site. One portion of the exhibit is devoted to the passage of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, which aimed to speed up executions by curtailing federal appeals.

Down the hall from Friot’s courtroom, an early architectural drawing of the Alfred P. Murrah building hangs on the wall, noting the year it was dedicated: 1977. This was the year Oklahoma passed the first law enshrining lethal injection as its new execution method — the first state in the country to do so. Developed by a local pathologist whom lawmakers had tasked with inventing something less barbaric than the electric chair, the method was soon adopted nationwide. In 2001, McVeigh became the first federal prisoner executed by lethal injection.

The method relied on a three-part formula: first a barbiturate to provide anesthesia; next a paralytic to prevent movement; and finally a fatal dose of potassium chloride to stop the heart. The first drug, sodium thiopental, was critical. As Roberts himself later conceded in Baze, “It is uncontested that, failing a proper dose … there is a substantial, constitutionally unacceptable risk of suffocation from the administration of pancuronium bromide and pain from the injection of potassium chloride.”

Whether sodium thiopental was being properly administered, however, could be hard to discern. The paralytic made it largely impossible to recognize signs of consciousness, particularly for those who attend executions — not medical experts, but journalists, lawyers, and family members on both sides. Although it mostly escaped notice at the time, one anesthesiologist recalled being unnerved by reports from media witnesses who described McVeigh shedding a tear during his execution. This was “a classic sign of an anesthetized patient being awake,” he said.

Evidence that states might be torturing prisoners to death eventually forced the Supreme Court to take up the question in Baze. But no sooner had the court upheld the country’s prevailing three-drug protocol than sodium thiopental began to dry up, in part due to activist pressure on international suppliers. Before long, death penalty states were seeking new drugs and new sources, increasingly relying on unregulated compounding pharmacies, with sometimes disastrous results.

Among them was Oklahoma. In 2014, the state turned to a three-drug method that mimicked the lethal injection protocol upheld in Baze. It simply replaced sodium thiopental with midazolam, leaving the other two drugs as before. But midazolam is a benzodiazepine, not a barbiturate. The former is most commonly used to treat anxiety or as a sedative during minor operations. Experts warned that midazolam was not capable of protecting a subject from experiencing the tortuous effects of the second and third drugs.

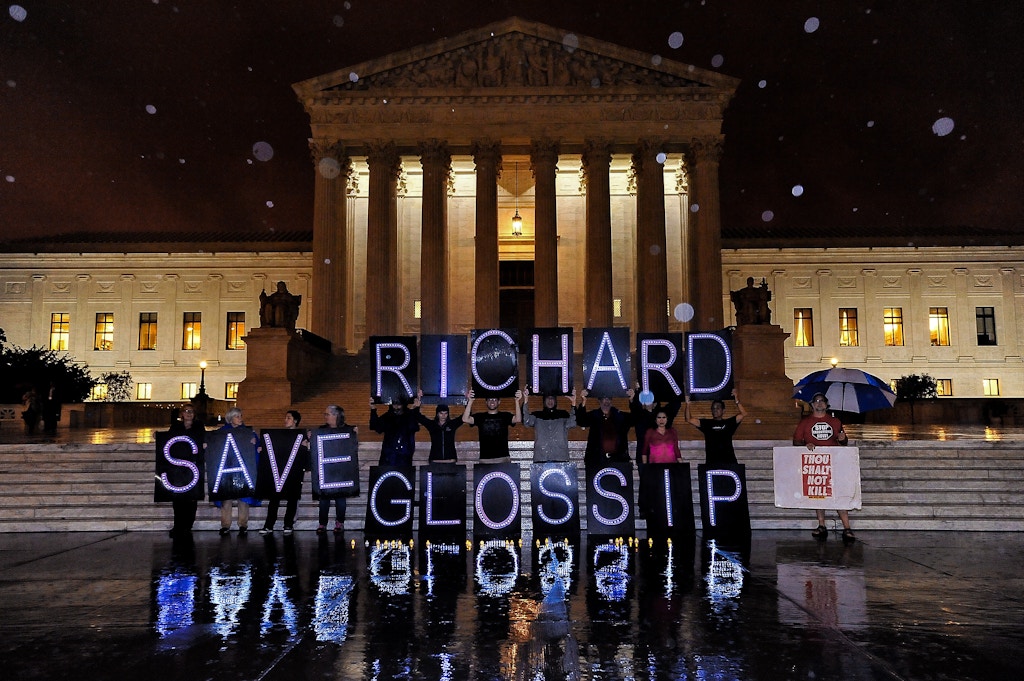

When the U.S. Supreme Court again took up lethal injection in 2015, Oklahoma’s protocol was at the heart of the matter. After the horrifying execution of Clayton Lockett in 2014, lawyers for Charles Warner, who was next in line to die, sought a preliminary injunction on behalf of their client and other men on death row, protesting Oklahoma’s “ever-changing array of untried drugs of unknown provenance.” Friot rejected the motion and the Supreme Court refused to intervene. Warner was executed in January 2015. His last words were “my body is on fire.” Shortly afterward, the court took up the lethal injection question, with Richard Glossip replacing Warner as the named plaintiff.

During oral arguments in Glossip v. Gross, Justices Samuel Alito and Antonin Scalia grudgingly acknowledged that midazolam was far from an ideal substitute for sodium thiopental but blamed activists for making the latter unavailable. Over the objections of Sotomayor, who accused the majority of ignoring evidence that midazolam would subject condemned people to the “chemical equivalent of being burned at the stake,” the court ruled 5-4 that the drug was good enough for them. “Because capital punishment is constitutional, there must be a constitutional means of carrying it out,” Alito wrote.

The ruling sent the litigation back to Oklahoma, where officials set out to execute Glossip despite mounting evidence that he was innocent. His execution was blocked at the eleventh hour, not by judicial order but by the state’s own incompetence: Moments before he was to be killed, officials realized that the prison was about to use the wrong drug. When it was revealed that the same erroneous drug had been used to execute Warner, officials put executions to a halt.

In the meantime, other states pushed forward with midazolam over the warnings of medical experts. Executions using midazolam in Arkansas and Alabama appeared to be badly botched, with witnesses describing gasping, lurching, and struggling. After a Tennessee man appeared to suffer on the gurney in 2018, several of his neighbors chose to die in the electric chair instead.

Yet none of those states have abandoned midazolam. And in those that have, it has not been due to any court ruling. After Arizona’s harrowing execution of Joseph Wood, lawyers for the condemned eventually settled a lawsuit with the Department of Corrections after it promised that it would “never again use midazolam, or any other benzodiazepine, as part of a drug protocol in a lethal injection execution.”

But perhaps most instructive is Ohio, where an execution has not taken place since 2018. After an evidentiary hearing convinced a magistrate judge that using midazolam would cause “severe pain and needless suffering,” the judge decried that the law prevented him from stopping an execution, since the condemned man’s lawyers had failed to prove that there was a better alternative. “This is not a result with which the court is comfortable,” he wrote. If not for the decision by Ohio’s governor to pause executions shortly thereafter, the execution would have almost certainly moved forward.

There was little reason to expect Friot to break this pattern. “I’m not a close follower of midazolam litigation in other states,” he told a plaintiff’s lawyer at the trial. “Has there been a final adjudication in any case determining that lethal injection using midazolam violates the Eighth Amendment?” The answer was no.

Photo: Larry French/Getty Images

Battle of the Experts

Friot entered the courtroom at 9 a.m. sharp on February 28. Appointed to the federal bench by President George W. Bush, he’d held senior status since 2014. With gray hair, a stern demeanor, and a biting impatience for anything that might be wasting his time, Friot made clear that he was ready to bring the yearslong litigation to a close. “I’m really not sure that any useful purpose would be served by having opening statements,” he told lawyers on both sides.

Representing 28 condemned plaintiffs was a group of veteran attorneys ranging from local federal defenders to corporate litigators from New York. On the opposite side of the courtroom, a group of young lawyers represented the Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office, among them 34-year-old Solicitor General Mithun Mansinghani.

A handful of TV and print reporters had been assigned to the trial, while elsewhere in the city, local press was covering a mounting crisis within the state’s Pardon and Parole Board, whose chair had resigned after being smeared by prosecutors who accused him of bias for voting in favor of clemency in death penalty cases. By comparison, the trial was largely devoid of human drama. Both sides agreed not to repeat the chilling testimony of lay witnesses to the execution of John Grant, which had been delivered at a previous proceeding. Instead, the trial was a so-called battle of the experts, with hours of technical testimony discussing thousands of pages of medical studies.

Much of the testimony was familiar to those who have followed past litigation. “It’s been known for some time that midazolam can only produce a level of sedation or deep sedation but cannot produce a level of general anesthesia, which is needed to prevent any perception of pain,” the first witness for the plaintiffs, pharmacology professor Craig Stevens, explained. Veteran anesthesiologist Michael Weinberger testified that the second and third drugs in the protocol, when administered rapidly and at extremely high doses, would be excruciating to a person who was not properly anesthetized. Both agreed that midazolam was known to have a “ceiling effect,” which would make even a massive dose inadequate to protect someone from suffering.

“It’s been known for some time that midazolam … cannot produce a level of general anesthesia, which is needed to prevent any perception of pain.”

Also familiar was Dr. Mark Edgar, an anatomic pathologist at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, who wore a short spiky haircut, thick-rimmed glasses, and Doc Martens. Beginning in 2016, Edgar had made a series of disturbing discoveries: evidence of pulmonary edema in the autopsies of people executed using midazolam. When Edgar cut into the lungs of one man executed in Ohio, he said, water spilled out onto the table.

In advance of the trial, Edgar had reviewed 32 autopsy reports from different states that relied on midazolam for lethal injection. Twenty-seven showed evidence of pulmonary edema, including John Grant’s and Bigler Stoufer’s. Grant’s autopsy showed signs of “intramuscular hemorrhage” on the tongue. This was something commonly seen in “victims of fires, it’s seen in drownings sometimes, and it’s sometimes seen in asphyxia from a variety of causes,” he said. Although autopsy reports were not yet available for Postelle or Donald Grant, there was good reason to expect similar results.

But while his findings were consistent, Edgar’s opinions had changed since his early days studying the autopsies of executed people. Where he previously believed that the pulmonary edema was “chemically induced” — that midazolam “was causing a burning, an acidic injury to the capillaries of the lungs” — the executions in Oklahoma in the run-up to the trial had given him pause.

Lawyers on both sides had hired experts to witness these executions — meaning that “for the first time, we’ve had trained observers, anesthesiologists, watching as these inmates were executed,” Edgar explained. Their observations suggested that what he was seeing in the autopsies was “negative pressure pulmonary edema,” which is caused by an obstruction in a person’s upper airways and worsens as they struggle to breathe. Edgar considered this an important revelation, which forced him to go back and reassess his previous conclusions.

The state seized on the contradiction. Mansinghani pointed out that Edgar’s conclusions supported the opinion of one of the state’s experts, anesthesiologist Ervin Yen, who had theorized that the pulmonary edema could be caused by a blockage in the airways. But whereas Yen claimed that the edema would occur after the condemned lost consciousness, Edgar disagreed. A person executed this way, he said, “would feel the sense of impending doom, of asphyxiation, of drowning, of terror.”

Edgar’s testimony cut to the heart of a problem with expert testimony on something as strange as lethal injection. There is no scientific body of research to show the effect of being injected with 500 milligrams of midazolam — a dose hundreds of times higher than what might be administered in a clinical setting. Edgar’s evidence-based work was, in many ways, as close as one could get. Since he’d first presented his findings publicly in 2018, additional research had revealed evidence of pulmonary edema in the autopsies of people executed using different lethal injection formulas, including barbiturates, which added yet another layer of questions to investigate.

But the legal system isn’t particularly accommodating of ongoing inquiry. In a courtroom, the most convincing experts are often those who offer firm conclusions, even if they amount to junk science. The Supreme Court’s decision in Glossip was largely based on the opinions of a single expert who had never administered midazolam to a patient — and whose report relied heavily on printouts from the website Drugs.com.

In theory, it’s up to a presiding judge to hold a hearing in advance of a trial to determine whether expert witnesses have the qualifications to peddle opinions on the stand. But Friot had explicitly discouraged challenges to the qualifications of the other side’s experts. In 21 years presiding over trials, he told the lawyers, he had yet to hold such a hearing — “and I don’t intend to do so here.”

Photo: Courtesy of Emma Rolls

Coping With Death

Hosch, the anti-death penalty activist, sat quietly in the second row over the course of the trial. She knew that the ruling was likely a foregone conclusion. Most people considered Friot’s decision to allow the recent executions to be the last word. As one advocate told her, “They used these four people as guinea pigs to justify killing the rest of the people on death row.”

Nevertheless, it felt important to be at the trial, especially for the families of people on death row. Most of them could not take time off work to sit in court all day. Others just could not bear to sit through testimony suggesting that their loved one had been tortured to death.

Donald Grant’s family was still reeling in the wake of his execution, she told me. And she received frequent text messages from the family of Gilbert Postelle, who had been executed a week before the trial began. “They are still just devastated,” she said. Unlike Grant’s family, Postelle’s relatives did not attend his execution. “He said that he did not want that to be the last image that they had of him. And it upset them,” Hosch said. “They didn’t want him surrounded by people who hated him. They wanted him to be surrounded by some people who loved him.”

Most of these men did not attract much attention outside Oklahoma. The exception was Julius Jones, who came within hours of execution in November 2021 amid a national movement proclaiming his innocence. Around Oklahoma City, street lamps and car windows still carried the message “Justice for Julius.” Meanwhile, questions loomed over the case of Richard Glossip. Despite evidence pointing to Glossip’s innocence, Hosch said that the attorney general would be seeking a death warrant as soon as a ruling came down in the state’s favor. “He’s going to try to get Richard executed as soon as possible.”

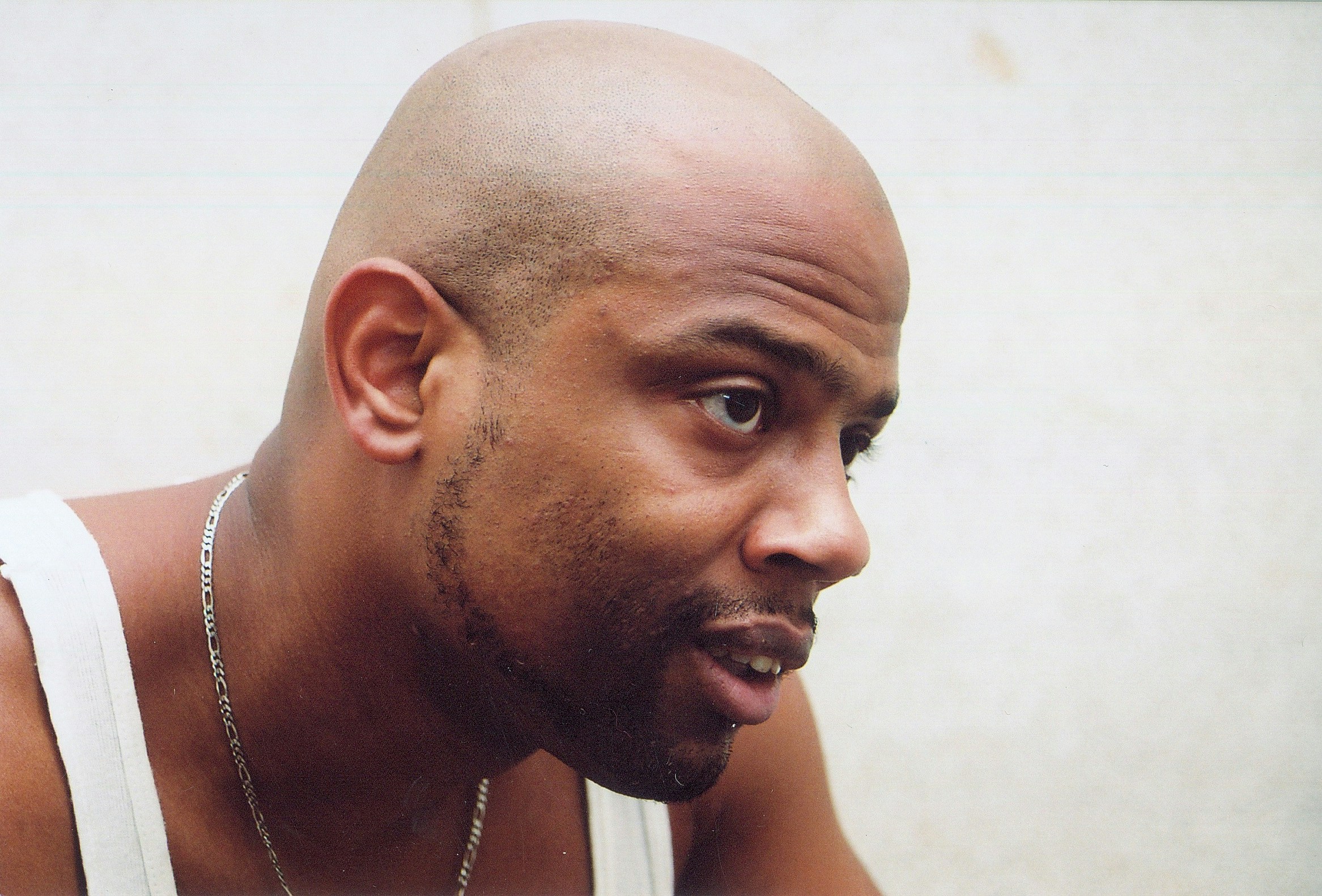

Grant did not have an innocence claim. He had committed a heinous crime: the murder of two women at a La Quinta Inn in 2001. The killings were senseless and violent. But they were also, in part, the product of lifelong mental illness that had never been treated.

Grant’s clemency petition provided a window into his background. Growing up in New York City in the 1980s, his family was in and out of shelters and welfare hotels, where he suffered profound abuse and neglect at the hands of those who were supposed to protect him. An older brother said in a declaration that their mother’s addiction to crack cocaine made her incapable of feeding her children, who resorted to stealing because they were hungry. Numerous relatives also said it was clear that Grant had mental problems starting in childhood. “I would ask him, ‘Who you talking to?’” one cousin said about Grant. Other times, “He would sit and just stare.”

After doing time in juvenile detention, then in adult prison, Grant followed his mother to Oklahoma City in 1999. His mental state had deteriorated by then. He had also become a devoted believer in the Five Percent Nation, an offshoot of the Nation of Islam that convinced Grant he was among a small fraction of people who knew the truth of the universe. “He used to say things that scare me that I didn’t know where it came from,” his mother later testified.

Two years later Grant went to a La Quinta hotel outside Oklahoma City, seeking $200 to bond his girlfriend out of jail, according to his clemency petition. After filling out a job application form, he shot and killed two employees, Brenda McElyea and Felicia Suzette Smith.

The trial was delayed for years because Grant was repeatedly found to be incompetent. According to his clemency petition, Grant was evaluated 18 times by a variety of psychologists, who consistently described him as showing psychosis and paranoia. Although he was given medication to render him competent for trial, he rambled incoherently on the stand, at one point claiming to have written the Bible. Other times he just seemed flat. “He had no facial expression, like he was a zombie,” one juror told Grant’s appellate lawyers. “He rarely spoke to his attorneys. They didn’t speak to him. It wasn’t a team. … I kept trying to figure out, ‘Is this man drugged?’”

A similar dynamic appears to have stymied Grant’s federal appeals — including in the challenge to Oklahoma’s lethal injection protocol. As Emma Rolls, head of the capital habeas unit of the Western District of Oklahoma, told me last year, “Many of our clients suffer from serious mental illness and cognitive limitations; they simply cannot understand how and why the law requires them to choose an alternative.”

But Grant’s refusal to choose an alternative method of execution reflected a communication breakdown on both sides. In a 2021 affidavit, Rolls, who was not in charge of the lethal injection litigation, wrote that neither she nor her co-counsel had discussed his decision until after he was dismissed from the lawsuit. “Mr. Grant has communicated his frustration with his habeas team for not discussing this issue with him directly,” she wrote.

The federal courthouse in downtown Oklahoma City on Feb. 27, 2022.

Photo: Liliana Segura/The Intercept

A Perverse Position

Some of the darkest moments in Oklahoma City stemmed from the requirement that lawyers offer better ways to kill their clients. In theory, there were plenty of methods to choose from — state lawmakers provided a backup plan should lethal injection become unconstitutional or “otherwise unavailable.” The default alternatives were laid out as electrocution, nitrogen hypoxia, or firing squad.

Under the Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling in Bucklew v. Precythe — which found that condemned people had to prove that their preferred method would substantially lower their risk of pain — lawyers did not have to limit themselves to execution methods already on the books. Regardless, lawyers for the condemned had settled on the firing squad. “While it may be gruesome to look at, we all agree it will be quicker,” one attorney told Friot at a pretrial hearing.

“While it may be gruesome to look at, we all agree it will be quicker.”

To make the case, the plaintiffs called an emergency physician and ballistics expert named James Williams, who had made a career training police in the use of deadly force through courses like “Shooting With X-Ray Vision.” Williams testified that execution by firing squad was “feasible” and “efficacious.” A bullet to the “cardiovascular bundle” would destroy the tissues of the heart, he explained. The subsequent “lethal arrhythmia” would immediately lead to a total loss of blood pressure. A person would be unconscious within seconds.

In order to show how swiftly a person would die upon being shot in the heart, Williams used an unsettling example: Kyle Rittenhouse’s 2020 killing of Anthony Huber following a Black Lives Matter protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Huber’s death was captured on video, and a medical examiner found that the bullet had gone through the left and right ventricles of his heart. According to Williams, Huber was unconscious within one to two seconds and dead shortly afterward. The same would be true of a person killed by trained marksmen. “This was done with an AR-15 rifle, which has about one-third of the ballistic energy of the rifles used in Utah firing squad protocol or the U.S. military firing squad protocol,” he said.

That attorneys working to save the lives of their clients would present such testimony seemed bizarre — even shocking. But it was also emblematic of the perverse demands now enshrined in the Supreme Court’s Eighth Amendment case law. Asking clients to choose methods like the firing squad was “inimical to the instincts and beliefs of people committed to capital defense,” Rolls told me last year. It also meant relying on antiquated evidence like Williams’s other main example: a 1938 newspaper article about a Utah man whose heart was monitored as he was executed by the firing squad. A photograph showed an electrocardiogram that captured the moment the bullets struck the man and his swift demise thereafter.

Given the comparative complexity of lethal injection — the frequently clumsy search for a vein, the often unreliable consciousness checks — it seemed like common sense that being shot through the heart might be less risky where pain was concerned. But prosecutors did their best to push back on Williams’s testimony. Wouldn’t it hurt if a person was shot in the ribs?

Particularly ironic was the state’s response to a pharmacology researcher who testified in support of a different alternative proposed by the condemned — a lethal injection formula relying on a barbiturate rather than midazolam. That witness said it should be relatively simple to produce barbiturates at an in-state lab. During a 2020 news conference announcing Oklahoma’s new protocol, the former Department of Corrections director openly described his attempts to find drugs for lethal injection as a “mad hunt” involving “seedy” people. “I was calling all around the world, to the backstreets of the Indian subcontinent, to procure drugs,” he said. But now the attorney general’s office expressed deep concern over quality control. Didn’t the production of barbiturates require certain licenses?

The final witness for the plaintiffs was Dr. Gail Van Norman, a professor of anesthesiology at the University of Washington in Seattle. Van Norman had reviewed eyewitness reports from the recent executions. She had also witnessed the execution of Postelle. In her professional opinion, all of these men had experienced pain and suffering, she said. “I think it’s a virtual medical certainty.”

Van Norman began with the execution of John Grant. Eyewitnesses said that Grant’s breathing became labored a few moments after the midazolam was administered. “At one point his back lifted dramatically off the gurney,” she said. These signs were consistent with an upper airway obstruction. “If we saw this in a patient in the operating room — I can’t imagine seeing it, but if we did — we would assume that the patient was awake, and we would do something about it.”

“We can’t rule out that the wrong drug was given.”

A post-mortem photograph of Grant was displayed on a monitor. Thick straps formed an “X” across his chest, and his outstretched hand was taped to the arm of the gurney. Yellow vomit could be seen on the pillow next to his head and on the floor. Yen, who had witnessed Grant’s execution on behalf of the state, concluded that this was merely passive regurgitation. But Van Norman rejected this. “If this was regurgitation, you would, at most, see stomach contents right next to the face,” she said. But this photo showed vomit some three feet away. If Grant was her patient, she would have assumed that he was conscious.

Van Norman saw red flags in all the executions, including those described by witnesses as uneventful. Her analysis of Postelle’s execution were especially vivid. She had sat in the front row.

After the announcement that the execution had begun, a Department of Corrections log marked the administration of midazolam. For the next two and a half minutes, Van Norman said, Postelle wiggled his hands and feet and blinked his eyes. At four minutes, he swallowed and his eyes closed partway. “I could still see eye movements,” she said — a sign that he was not fully anesthetized.

At four and a half minutes, Van Norman noticed that Postelle’s breathing appeared to be obstructed. His chest was “collapsing in” and his thyroid cartilage was “pulling down.” After the paralytic was administered, three media witnesses saw something she considered especially alarming: a tear on Postelle’s cheek. “Tearing is a sign of extreme distress,” Van Norman said. In an operating room, it would mean that a patient is “perceiving stress and pain and we should do something about it.”

But perhaps most disturbing to the spectators in the courtroom was a photograph of a monitoring strip that had been provided by the Department of Corrections. “It says ‘rocoronium,’ which is not the drug that’s called for in the Oklahoma protocol,” Van Norman said. Although it is a paralytic like vecuronium, the second drug in Oklahoma’s formula, it is not interchangeable at the same dose. “Does this suggest that perhaps the wrong drug was used?” a lawyer asked Van Norman. “We can’t rule out that the wrong drug was given,” she said.

Bottles of midazolam at a hospital pharmacy in Oklahoma City on July 25, 2014.

Photo: Sue Ogrocki/AP

Midazolam Roadshow

The third day of the trial fell on Ash Wednesday. That afternoon, Dr. Joseph Antognini took the stand for the state. Bald and bespectacled, he wore ashes in the shape of a cross on his forehead.

An anesthesiologist and professor at the University of California, Davis, Antognini is perhaps best known for lending his expertise to President Donald Trump’s Justice Department during its federal execution spree, arguing that executing two people with Covid-19 would not heighten their risk of suffering. More recently, he attended the execution of Donald Grant.

Antognini returned to a subject that had been repeated ad nauseam over the previous few days: the difference between induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. From the start of the trial, the plaintiffs’ experts had acknowledged that midazolam could be useful for preparing a patient for surgery. However, they stressed that the drug was not sufficient to be used on its own to keep a patient asleep and insensate. The Food and Drug Administration label for midazolam noted that it could be used “intravenously for the induction of general anesthesia before the administration of other anesthetic agents.”

Despite this language, Antognini pointed to the FDA label as evidence that midazolam could be used on its own to anesthetize a person for lethal injection. He cited a slew of medical studies that, upon closer reading, appeared to undermine his position. One explicitly said that “midazolam cannot be used alone … to maintain adequate anesthesia.” At one point, Friot asked Antognini directly if he would ever use midazolam on its own for a brief procedure. “If it was short … where it was going to literally take 30 seconds, then I might say ‘go ahead,’” he said.

Nevertheless, Antognini testified that Grant’s execution had gone smoothly. When the curtain went up shortly after 10 a.m., “the inmate was on the table.” He lifted his head and looked around. “He was laughing and smiling,” Antognini said. He could not understand Grant’s final statement, he added. “He was saying a lot of things that, quite frankly, didn’t make sense to me.”

After the midazolam was administered, Antognini said he saw a “rocking boat motion,” in which the abdomen starts to rise and the chest falls while the muscles around the tissues of the neck collapse. “That’s an indication of an airway obstruction,” he said. But he added that the motion was relatively mild. A few minutes later, a staffer entered the chamber to do a consciousness check, rubbing Grant’s sternum and pinching his arm. “Donald! Donald!” the person called out. There was no response.

Around 10:11 a.m. Antognini saw bubbles going through the IV, presumably the vecuronium. Shortly afterward, Grant’s breathing stopped. “I wasn’t able to see much of anything else in terms of the color change because it’s a dark-skinned individual,” Antognini said. But he could see that Grant’s lips had turned blue. He also saw a small amount of blood enter the IV tubing, which caught his attention. There were a number of explanations, he said, but he did not consider it concerning. “I just thought, ‘Oh, that’s interesting, I wonder what happened there.’”

The final witness for the state was Yen, the anesthesiologist. A former Oklahoma state senator and current candidate for governor, he recently left the Republican Party and became an independent, citing the GOP’s refusal to recognize the Covid-19 pandemic as “the straw that broke the camel’s back.” Unlike the other experts on both sides, Yen had not testified about lethal injection in other states, which seemed to please Friot. “Some of the opposing experts in this case have squared off in other midazolam challenges in other courts around the country, in what amounts to a midazolam roadshow,” he wrote in his ruling after the trial. Yen was the “one fresh face in this case.”

Yen certainly had the right credentials. He had served as president of the Oklahoma Society of Anesthesiologists and as chief of anesthesiology at a local hospital. But like Antognini, his testimony sometimes seemed to undermine his own position. Yen said he used midazolam several times a week. In fact, he had used it just one day earlier to treat a patient who had an infected ulcer on her foot. But even for that minor procedure, Yen did not rely upon midazolam alone; he used some fentanyl as well.

Yen had attended three of the executions carried out in advance of the trial. Each time, he concluded that the condemned had been properly anesthetized. At a hearing following the killing of John Grant, his testimony persuaded Friot that despite signs to the contrary, Grant had not suffered. “The important point here is that all of this occurred while Grant was unconscious and insensate to pain as a result of the administration of a massive dose of midazolam,” Friot wrote in his order allowing the next executions to proceed.

On the stand, Yen reiterated what he had argued in his previous reports. With the post-mortem photograph of John Grant once again displayed, he was firm that what was visible was not vomit per se, but the product of passive regurgitation. “I guess they fed the guy” is how he summarized his reaction upon seeing this in the execution chamber.

The trial ended on March 7. Before adjourning, Friot told the lawyers that he had taken 103 pages of handwritten notes. “I could not look at myself in the mirror as a U.S. district judge if I had sat down a week ago with anything other than an open mind,” he said. As both sides awaited a ruling, autopsy results were finally released for Postelle and Donald Grant. Both showed evidence of pulmonary edema. Friot’s ruling came down two weeks later. “It is safe to say that pulmonary edema is found in many inmates — it might well be the vast majority — executed by lethal injection,” he wrote. But he was satisfied that it occurred only after the condemned was “insensate to pain.”

Friot acknowledged that midazolam might not be ideal. But the Supreme Court had made clear that it was good enough. “The evidence persuades the court, and not by a small margin, that even though midazolam is not the drug of choice for maintaining prolonged deep anesthesia, it can be relied upon, as used in the Oklahoma execution protocol, to render the inmate insensate to pain for the few minutes required to complete the execution.”

Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images

Ghost of a Chance

A few weeks after the trial, Joe Robinson was in his apartment in New York City. A large U.S. Postal Service box sat in his living room with an orange sticker that read “Cremated Remains.” The ashes of his brother Donald Grant had been delivered one day earlier. It had taken almost two months for them to arrive.

Robinson was only beginning to process losing his brother. As the oldest, he had taken charge of logistics like tracking down the ashes from the funeral home in McAlester while also checking up on his surviving siblings. All of them were in pain. “There were five of us,” he said, listing their names and birthdays. “Now there are four of us.”

Robinson did not need to read the clemency petition in his brother’s case. He knew his story all too well. Although he’d spent much of his childhood in the same environment, their mother had doted on Robinson. “I knew she loved me and she told me how smart I was and this was crucial for me as a child,” he wrote in an affidavit included in the petition. “Donald, however, did not get the same kind of love or support.” Herself a victim of abuse, their mother beat Grant excessively, sometimes locking him in the closet. “She never did that to anyone else.”

Robinson made no excuses for his brother’s crimes — or his own. He had gotten caught up in the drug trade and went to prison for 25 years. But he committed himself to education while in prison, passing on his lessons in a 2007 book for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people. “Point blank, you were not born to commit crimes; you were not predisposed to commit vicious and antisocial acts,” he wrote in the introduction. But he knew what it was like to see no other options. When it came to his brother, he told me, “I always said he didn’t have a chance.”

Robinson was haunted by something Grant said during one of their last visits, “I didn’t want this life,” he said. “I didn’t want to rob people. I didn’t want to commit crimes.” Unlike his brother, Robinson had been given a chance to overcome his mistakes. A filmmaker had even chronicled his love story with his wife, Sheila, through the letters they exchanged when he was in prison. The couple had flown to attend the execution on their 17th wedding anniversary. “So now every time I think of our anniversary, I’m gonna think about that.”

It was hard to discuss the execution itself. Every step had been carefully scripted in a way that felt almost theatrical. In the front row, Robinson held his wife’s hand in silence. When the curtain came up, his brother looked up at them from the gurney, then said, “I’m solid. I’m good.” He asked Sheila to take care of his brother. Then he recited an Islamic prayer followed by sayings that Robinson recognized as Five Percenter language. It was hard to follow. But some witnesses described Grant as simply sounding crazy, which bothered Robinson. “He didn’t sound like a lunatic to me.”

I asked Robinson about his brother’s fear and paranoia about a botched execution. It was true that Grant was terrified, he said — he used to call him first thing in the morning obsessing about it. But the label of paranoia did not sit right. “His paranoia, I think, did come from his experiences … in prison and institutions in general,” Robinson said. His brother saw what had happened to other Black men condemned to die in Oklahoma — men like Clayton Lockett, Charles Warner, and John Grant. “He wasn’t wrong for thinking like that.”

Robinson did not follow the lethal injection trial closely. But after the ruling came down, he saw news reports about Oklahoma planning to execute 25 more people. He found it unfathomable. “What could be more cruel than that?”

Discussion about this post