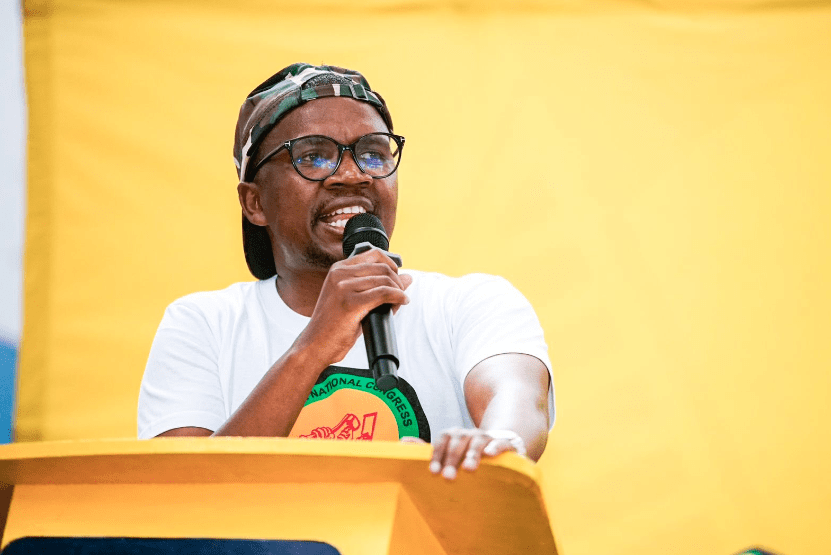

Eleventy seventh: Former president Jacob Zuma is going after Chief

Justice Raymond Zondo. Photo: Mlungisi Louw/Getty Images

Thursday.

Another day, another gambol through South Africa’s high courts by Jacob Gedlehlekisa Zuma, our beloved — to some — former head of state and our fair Republic’s most prolific — and least successful — serial litigant.

This time, Team Zuma wants the Pretoria high court to set aside the appointment of Chief Justice Raymond Zondo by president Cyril Ramaphosa.

According to uBaba’s latest set of court papers, Ramaphosa’s appointment of Zondo was irrational and unconstitutional and should not have taken place.

Zuma’s team argue that el jefe’s decision to put in place a panel to advise him on the suitability of the candidates who had been nominated to replace then chief justice Mogoeng Mogoeng was also flawed.

They say that Ramaphosa should have appointed current Deputy Chief Justice Mandisa Maya, recommended for the post of chief justice by the panel that he should not have appointed, instead of Zondo.

The presidency says the application is just another attempt by Zuma to harass Ramaphosa after the failure of his efforts to allow the courts to bring a private prosecution against him.

It also appears to be a warm-up for another by Zuma to have the findings of the Zondo commission into state capture set aside — or at least halt their implementation against him and others identified as having facilitated and benefited from the looting of state coffers.

The application is no surprise.

There is a very important election coming up, and for all Zuma’s support in his home province, where the ANC leadership wants him to campaign, he and everybody placed at the scene of the crime by Zondo will be breathing shallowly between now and May.

Nobody wants to be the sacrificial lamb dragged out to illustrate just how serious the ANC — and the state — are about dealing with state capture, least of all uBaba.

Nxamalala really does love a lawyer’s letter — as long as it’s not addressed to him.

Zuma has filed papers about just about everybody, except himself, since he was first charged for taking bribes from Schabir Shaik in 2005, so I guess it was Zondo’s turn — and Ramaphosa’s — again.

There’s still time.

I lost count at the eleventy seventh of the number of applications brought by Zuma against the president, the judiciary, the prosecution service and pretty much everybody who has tried to have him account for his actions.

That was around the time he was jailed for contempt for refusing to be cross-examined by the state capture commission — chaired by none less than Zondo himself — a man described by Zuma in his court papers as a friend.

Not the most conventional show of affection, the way most people would treat their friends. Then again, uBaba isn’t your run-of-the-mill former head of state.

Like the majority of Zuma’s romps in the courtroom, the eleventy seventy application failed and Nxamalala got 15 months in the slammer, although that was cut short when uBaba was sent home on medical parole.

Since then, the lawyer’s letters from uBaba’s legal team haven’t stopped flying, a blizzard of pleadings, heads of argument, affidavits and counter pleadings that have achieved exactly zero, beyond dragging out the inevitable.

Only God, and Zuma’s lawyers, know how many applications he has brought since then — an incessant flurry of allegations, insults and conspiracy theories dressed up as legal arguments which have been — rightly — kicked to the curb by a succession of judges.

It’s hard to think of anybody in the history of litigation who has lost more cases than uBaba and his team.

Historically speaking, the last time Team Zuma won a court case, Thabo Mbeki was still president of the country.

That all changed — quickly and brutally — with the governing party axing Mbeki before the ink on Judge Chris Nicholson’s judgment had time to dry properly.

One thing led to another, and by the time VAR was called on the decision Mbeki was long gone and Zuma was in — along with the Gupta brothers and the comrades who wanted TM1 fired for failing to let them “put a little money in their pockets”.

uBaba must have thought his legal dramas from the Shaik payments were over and that he was home and dry, free to count the takings, clean out the prosecution service and line up the big payday he had been waiting for.

But, eventually, uBaba got his day in court, just not in the one — or under the conditions — he wanted.

Discussion about this post