In an extraordinary year for the Earth’s climate – which is now virtually certain to be hottest on record – global warming has combined with the El Niño weather phenomenon and other factors to cause “crazy” weather across the globe, including in Africa.

The continent has faced a run of deadly and, in many cases, unprecedented extreme weather events this year.

By far the most lethal was Libya’s “medicane”-fuelled floods, which killed more than 11,300 people in September.

But while Libya’s floods made global headlines, many other deadly extreme events in Africa failed to make international news.

Carbon Brief has combined disaster data, humanitarian reports and local news stories to create a more complete picture of the scale of extreme weather impacts in Africa in 2023 to date.

The investigation shows that at least 15,700 people have so far been killed in extreme weather disasters in Africa in 2023. A further 34 million people have been affected by extremes.

It also shows that:

- More than 3,000 people were killed in flash floods in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda in May. Scientists were unable to assess the role of climate change in the disaster because of a lack of functioning weather stations recording data in the region.

- At least 860 people were killed in floods and mudslides in February during Tropical Cyclone Freddy, the longest lasting cyclone on record affecting Madagascar, Mozambique, Mauritius, Malawi, Réunion and Zimbabwe.

- More than 29 million people continue to face unrelenting drought conditions across Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya, Djibouti, Mauritania and Niger.

- Southern African countries have sweltered in a months-long winter heatwave, leaving many facing summer-like conditions for a continuous year.

Carbon Brief also spoke to scientists about how these events could be linked to climate change and other factors, including high vulnerability and a lack of preparedness – and why so many of Africa’s extreme weather events go unrecorded and unreported.

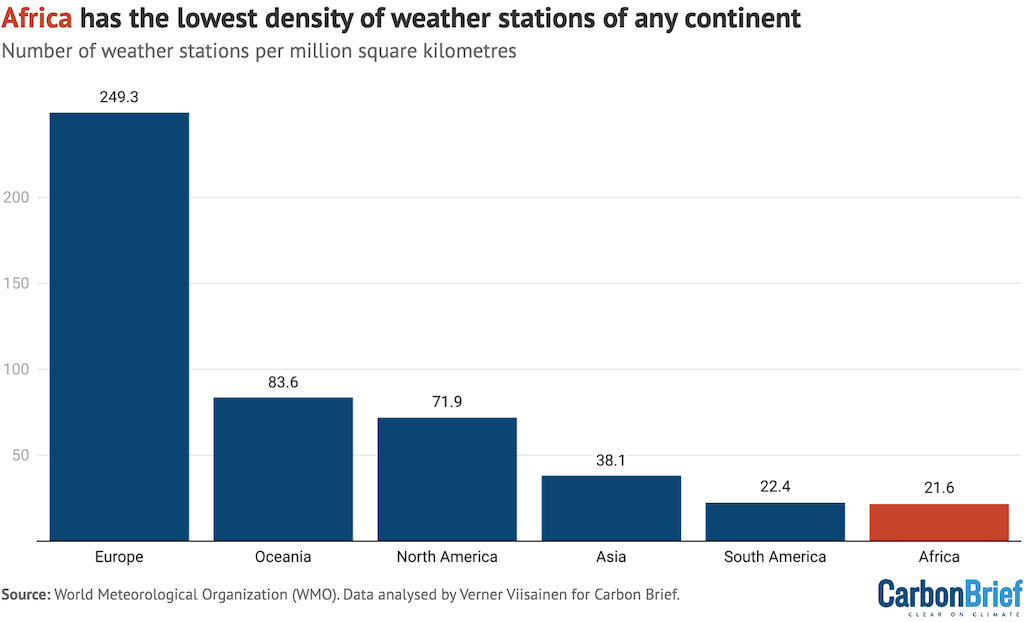

In addition, Carbon Brief analysis shows that Africa has the lowest density of weather stations out of any continent – making it difficult to know the extent to which extreme weather is happening and how it might be shifting because of climate change. A climate scientist from Kenya describes this as “extremely worrying”.

She adds that the toll of extreme weather on Africa’s people in 2023 is a stark reminder of why the developed world must take responsibility for the “loss and damage” caused by climate change.

Extremes mapped

Africa is one of the most vulnerable continents in the world to climate change, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Seven of the 10 countries most vulnerable to climate disasters are in Africa, according to an analysis from the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and the World Resources Institute (WRI).

According to this analysis, the countries most vulnerable to climate disasters are those that have low “climate readiness” – measured by examining the threats that climate change poses to a country and that country’s ability to protect its citizens – and high levels of “fragility” – the likelihood that a country will experience societal collapse in the event of a disaster.

The threats posed by climate change are rising with greenhouse gas emissions, of which Africa is responsible for just 2-3%.

In 2023, every part of the continent was affected by extreme weather disasters, ranging from catastrophic flooding in Libya to intense heat in Malawi.

To study these events, Carbon Brief has combined UN humanitarian reports and local news stories with data from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT), which was launched in 1988 by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) in Belgium.

The map below shows extreme weather disasters affecting Africa in 2023 to date, according to the EM-DAT database and further analysis by Carbon Brief. On the map, the size of the circles correspond to the number of people affected by the event, while a colour key indicates the event type.

For an extreme event to be featured on the EM-DAT database, it must fulfil one of the following criteria:

- 10 or more people killed.

- 100 or more people affected.

- The declaration of a state of emergency.

- A call for international assistance.

(It is worth noting that the EM-DAT is the largest disaster database available, but is still not exhaustive, particularly for African nations.)

Extreme weather events in Africa in January-October 2023. Data source: Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) and further research by Carbon Brief. (Not all extreme events are captured by EM-DAT.) Map by Joe Goodman and Tom Prater for Carbon Brief.

Carbon Brief’s analysis of EM-DAT data, humanitarian reports and local news reports shows that at least 15,700 people have been killed in extreme weather disasters in Africa in 2023 to date.

This is a major jump from the 4,000 people killed by extreme weather disasters in 2022 – but it is worth noting the vast majority of deaths (11,300) occurred during Libya’s record floods.

The analysis also shows that at least 34 million people were affected by extreme weather disasters in 2023. This compares to 19 million people in 2022.

Overall, weather events in Africa this year fit into a global picture of record and, in some cases, uncharted extremes, climate scientists tell Carbon Brief.

The reasons why 2023 has seen such extreme heat and unusual weather events are still being debated by scientists. However, known contributors include the 1.3C of temperature rise already caused by humans and El Niño, a natural phenomenon that tends to drive up global temperatures and affect weather in many parts of the world, including Africa.

Dr Izidine Pinto, a climate scientist from Mozambique currently working at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, tells Carbon Brief:

“This year is very unusual worldwide. In Africa, almost every month, there were record monthly temperatures. And we know that El Niño is associated with below average rainfall in many parts of Africa, especially in southern Africa.”

Some of the weather events in Africa this year have left scientists scratching their heads, adds Dr Joyce Kimutai, a climate scientist from Kenya currently working at the Grantham Institute – Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Climate change is really disrupting the climate system. To me, I think it’s challenging, it’s difficult and it’s also dangerous in a way because as climate scientists we don’t know exactly what’s happening. Every time we think we’ve understood the system, things keep changing. So we would think that we can inform the public about the risks that they can anticipate and how they need to prepare, but then the system is also playing games with us.”

Kimutai adds that the toll of extreme weather events on African lives in 2023 is a stark example of “loss and damage” – a term to describe how climate change is already harming people, especially the world’s most vulnerable. She says:

“We are not on track to limiting warming to 1.5C. That means we will continue to experience these extreme events and that is going to cause more damage to communities. At the same time, people in these countries will have to continually dig deeper into their pockets to deal with these recurring events. What that means is the loss and damages that we know will continue to grow.”

Loss and damage is expected to be a major talking point at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai starting in late November, after a historic fund for such damages was agreed at COP27 in Egypt.

Floods

Floods affected every corner of the African continent in 2023.

Carbon Brief analysis shows at least 23 flood disasters occurred, with countries affected including Angola, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Guinea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Liberia, Libya, Mauritania, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Rwanda, Somalia, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia.

By far the most deadly were Libya’s floods. In September, a highly unusual cyclone called Storm Daniel dropped a torrent of rainfall over the coast of Libya.

The water quickly overwhelmed two old and damaged dams in the coastal city of Derna, resulting in tsunami-like waves that swept people and houses out to sea. The disaster killed more than 11,300 people.

A rapid analysis released in the storm’s wake found the extreme rainfall was made up to 50 times more likely and 50% more intense by climate change.

Storm Daniel was a “medicane”, the name given to a storm originating in the Mediterranean Sea that has the physical features of a hurricane.

Scientists told Carbon Brief that medicanes are currently rare, but there is evidence that they are becoming more intense because of climate change.

One reason for this is when sea surface temperatures are extremely high, it allows storms to gather up more “fuel” as they travel over the ocean – making them stronger when they eventually make landfall.

We have a #medicane in the making. Storm #Daniel in the Mediterranean now has tropical characteristics heading south and will make landfall tonight near Benghazi, Libya. The dark shades of purple are winds 50 mph+ pic.twitter.com/3J3ZTnCEDU

— Jeff Berardelli (@WeatherProf) September 9, 2023

As well as climate change, the disaster in Libya was worsened by other factors, such as the age of the dams that became overwhelmed with water and an incoherent system for warning the public of the dangers posed by the storms, experts told Carbon Brief.

Another deadly flood to strike Africa in 2023 took place in May, when severe flooding around Lake Kivu devastated communities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda.

According to Carbon Brief analysis, these flash floods killed 2,970 people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and 131 people in Rwanda.

Many families living in the region had escaped conflict and were living in temporary accommodation, leaving them extremely vulnerable.

More than 120 people were killed Tuesday as the worst floods in years battered DRC’s capital Kinshasa following an all-night downpour. Major roads in the city of some 15 million people, were submerged for hours, & a key supply route was cut off. #ClimateCrisis pic.twitter.com/fvPJ4MULLJ

— Fridays For Future Uganda (@Fridays4FutureU) December 14, 2022

Kimutai led a team of scientists who tried to understand how climate change influenced the likelihood and severity of these floods.

However, the researchers were unable to carry out their analysis because they were not able to find reliable rainfall data from weather stations in the region, she explains:

“From the DRC side, we couldn’t find any observational data to use. There have been issues with conflict for a long time and when a country’s at war, almost everything is dysfunctional. What you find with instability is that government employees are not likely to be able to constantly man weather stations and ensure their day-to-day running.”

She adds that the researchers also tried to use satellite information in the place of weather station data. However, data obtained from different satellites did not match up, making it impossible to tell exactly how much rainfall fell during the deadly flash floods.

More on the impact of low weather station coverage in Africa is included in: Why do African extremes go ‘unreported’?

Cyclones

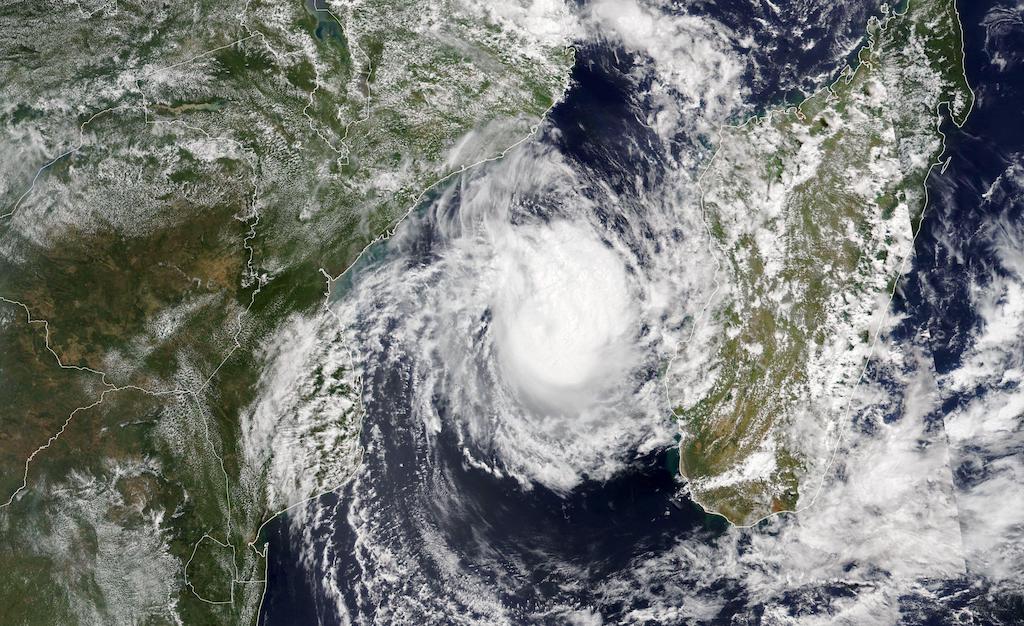

Southern Africa was on the receiving end of a record-breaking – and highly unusual – storm this year called Tropical Cyclone Freddy.

Tropical Cyclone Freddy began as a disturbance near Australia in February and crossed the entire Indian Ocean to make landfall on Madagascar.

The storm then crossed the Mozambican channel to hit Mozambique and surrounding countries. It then returned to the Mozambican channel for several days, before striking Mozambique for a second time. It then proceeded inland towards Malawi.

Overall, the storm persisted for 34 days – making it the longest-lasting tropical cyclone on record. (This record is awaiting verification from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).)

It also covered a distance exceeding 8,000km. Pinto, who is originally from Mozambique, tells Carbon Brief:

“It made landfall in Mozambique twice, which is very unusual for a tropical cyclone in my living experience. I have never seen a tropical cyclone make landfall and then go back to the ocean before returning again. And this one travelled northwards, which is also unusual because tropical cyclones usually travel from north to south.”

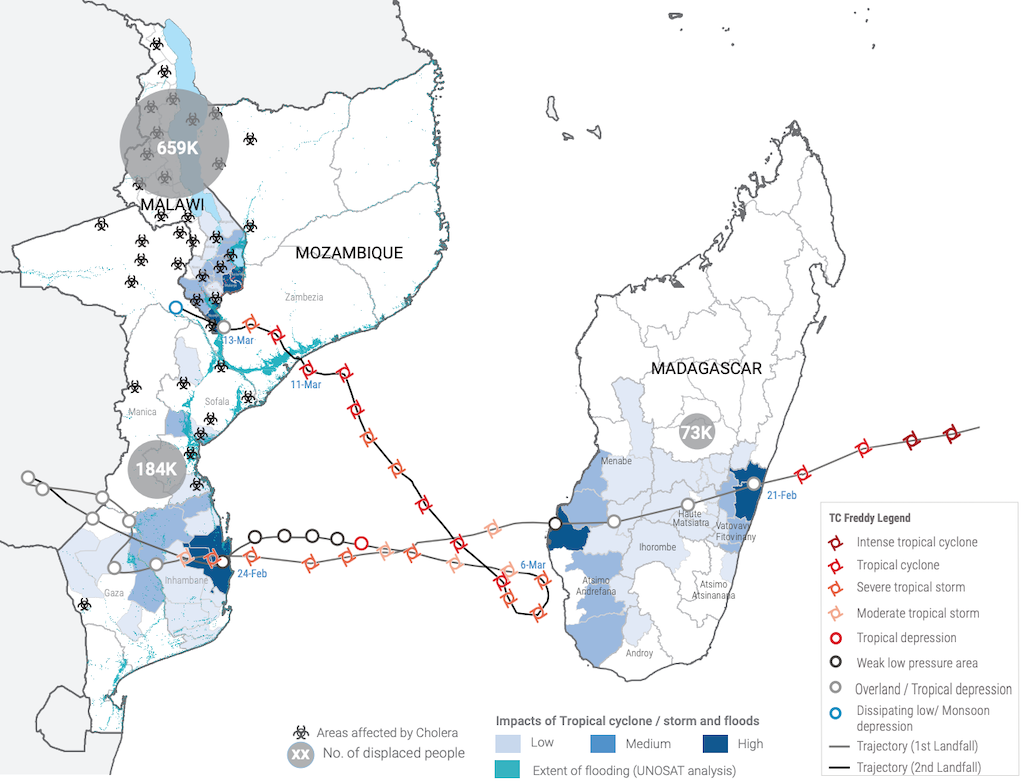

The remarkable path of Tropical Cyclone Freddy is outlined in the diagram below, which was produced by the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

(The diagram also uses blue shading to show what areas experienced the most flooding and bubbles indicating where the most people were affected.)

According to Carbon Brief analysis, at least 860 people were killed in floods and landslides associated with the storm across Madagascar, Mozambique, Mauritius, Malawi, Réunion and Zimbabwe.

The storm also destroyed 408,000 houses and 6,600 square kilometres (km2) of cropland across Malawi, Mozambique and Madagascar, according to OCHA. Floodwaters from the storm also assisted several outbreaks of the deadly waterborne disease cholera (indicated with hazard signs on the diagram above).

There has been no analysis into the role of climate change in intensifying Tropical Cyclone Freddy.

However, according to Pinto – who, along with Kimutai, works to analyse the role of climate change in Africa’s extremes with the World Weather Attribution group of scientists – it can be assumed that warming did have an impact on the storm. He explains:

“We did not do a study because previously we’ve done two studies on Tropical Cyclone Batsirai and storm Ana [which affected southern Africa in 2022], and we found that climate change played a role in the amount of rainfall caused by these two tropical cyclones. If we analysed Tropical Cyclone Freddy we would probably find the same answer.”

He adds that the latest findings from the world’s authority on climate science, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), show that eastern southern Africa is likely to see an increase in average tropical cyclone wind speeds and rainfall, as well as a higher proportion of category 4 and 5 (the most severe) storms, as climate change worsens.

“From the scientific literature, it is clear that climate change played a role,” he says.

Heatwaves

Many parts of Africa faced extreme heat this year.

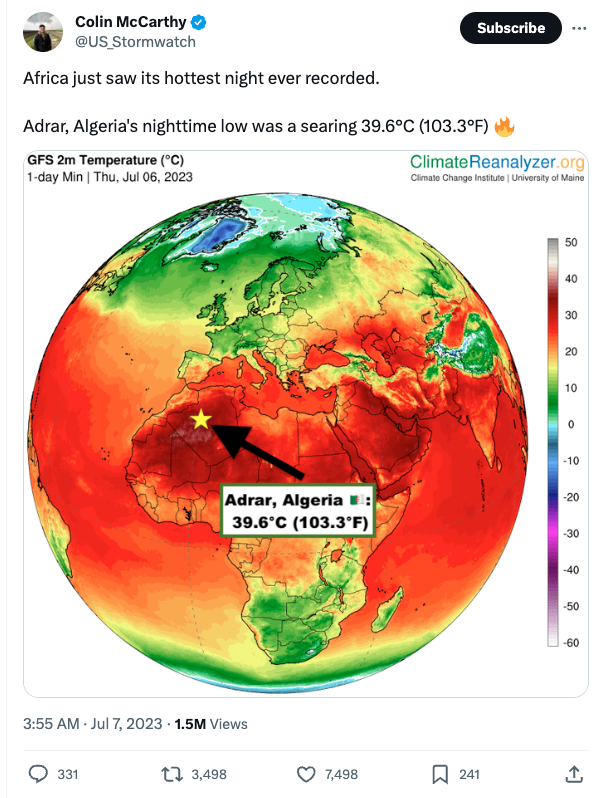

The north of the continent saw record temperatures during an extreme summer heatwave that affected each of Earth’s seven continents in July.

During this heatwave, Algeria hit 48C, while Morocco faced 47.5C heat.

Adrar in Algeria also experienced Africa’s hottest night on record in July, when night-time temperatures did not fall below 39.6C.

Al Jazeera reported that the extreme temperatures particularly affected migrant workers in Tunisia, who typically sleep rough in tents in the nation’s capital, Tunis.

All Africa reported that 47C heat had a “profound impact” on humans and livestock in Niger.

An analysis by the World Weather Attribution team found that the heat observed across the northern hemisphere in July would have been “virtually impossible” without climate change.

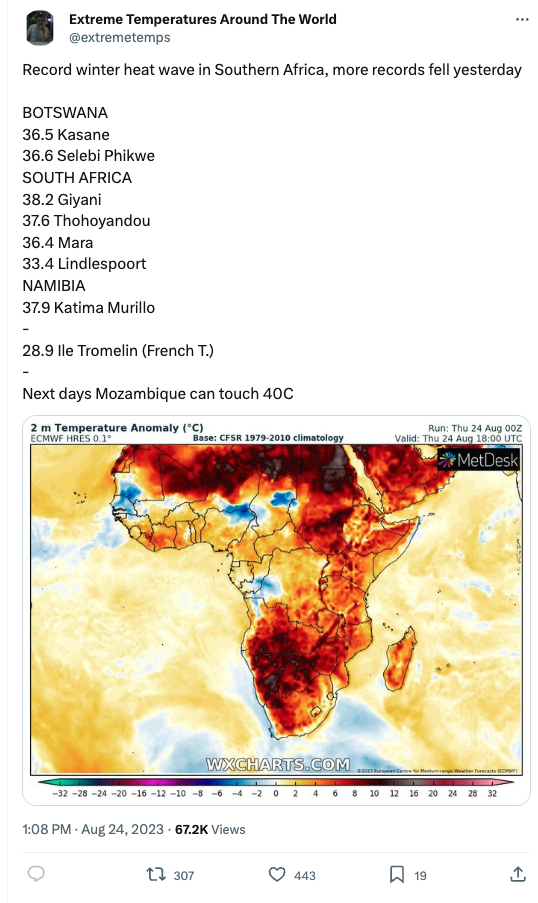

The south of the continent, meanwhile, endured prolonged high temperatures in what were meant to be the winter months.

In August, the Washington Post reported that Southern Africa was in “the midst of a major heatwave” delivering temperatures close to 40C to Botswana, South Africa, Namibia and Mozambique.

In October, the Guardian reported that Malawi was experiencing temperatures 20C above the seasonal average. (Malawi’s cool season typically runs from May to October.)

The prolonged winter heat meant that many southern African countries effectively faced a 12-month long summer, Kimutai says:

“We witnessed for the first time a winter heatwave in southern Africa. People say it didn’t get cold at all this time. It was just like one long back-to-back summer.”

Despite these record events, the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) did not register any heatwave disasters in Africa this year (see map above). More explanation of why Africa’s heatwaves often go untracked is included in: Why do African extremes go ‘unreported’?

Wildfires

The extreme heat in northern Africa this year fuelled deadly wildfires.

Reuters reported that wildfires swept across Algeria in July, requiring a response from 8,000 firefighters. The flames killed 34 people, including 10 soldiers.

The newswire added that blazes also ripped across Tunisia, forcing hundreds of households to flee.

Drought and famine

Numerous African countries continued to be gripped by severe drought this year. Many of these droughts have spanned several years.

According to Carbon Brief analysis, more than 29 million people faced unrelenting drought conditions across countries including Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mauritania, Niger and Somalia in 2023.

According to a report from the UN World Food Programme (WFP) in July, drought in the Horn of Africa has left more than 23 million people facing food insecurity and more than five million children facing acute malnutrition.

The report says:

“The drought affected livestock body conditions and decimated herds, which, in turn, curbed livestock production. Successive below-average harvests, coupled with high production and transport costs, reduced local agricultural produce. All this led to food price spikes that still persist, which reduced household purchasing power and access to nutrient-rich foods.”

An analysis released by the World Weather Attribution service in April found that persistent drought in Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia “would not have [happened] at all” without human-caused climate change.

A “conservative estimate” from the scientists said that the drought conditions seen in the Horn of Africa over 2020-22 were made at least 100 times more likely by climate change.

In July, the WFP said the impacts of drought conditions in this period are “likely to persist for a long time” despite some improvements in rains in recent months.

Reacting to the analysis in April, Mohamed Adow, director of the Power Shift Africa thinktank in Kenya, said the findings reinforce why climate change is “the world’s biggest and gravest injustice issue”. He told Carbon Brief:

“As someone from East Africa it’s painful to see the impact of climate change wreaking so much suffering on people that have done nothing to cause this.”

Why do African extremes go unreported?

African activists, scientists and policymakers have warned for years that African extreme weather events often go “unreported” when compared to those in North America and Europe.

Understanding the extent to which African extreme weather events are unreported is complicated.

One way to do this is to consider all the ways that extreme weather events are recorded and reported.

Primarily, extreme heat, rainfall and wind speeds – the ingredients of most extreme weather events – are monitored by weather stations.

Carbon Brief’s analysis of WMO weather stations reveals that Africa has the lowest density of operational stations out of any continent.

Pinto tells Carbon Brief that a lack of weather stations in Africa has limited the tracking of extreme weather events for decades:

“The low density of weather stations is something that limits research and also monitoring of extreme events.”

Without adequate data from weather stations, scientists are not only struggling to track when extreme weather events happen, but they are also left without the historical records needed to understand how events have shifted over time because of climate change, he says.

Kimutai – who was prevented from assessing the role of climate change in deadly floods in the DRC this year by a lack of weather station data – tells Carbon Brief that the lack of weather station data from Africa is “extremely worrying”:

“The reason why I’m extremely worried is because we’ve seen the planet continuing to warm with increasing magnitudes of extreme events – this means the continent is likely to be battered more by these extremes. Without observations, we have a minimal understanding of the climate system so we can’t anticipate how the risks are changing. This means that we can’t adequately prepare.”

As well as having the lowest density of meteorological weather stations, the African continent also has by far the fewest radar weather stations. These kind of stations are needed to warn people about upcoming rainfall, Pinto says:

“If you have a radar, you can see rain coming into the region – and then you can tell people that rain is coming and you can plan. In many parts of Africa, that’s not available because radars are very expensive.”

Even when weather data is recorded, there are other ways that extreme weather disasters can be missed.

In Africa, the most potent example of this occurs with heatwaves.

Human-caused climate change has led to an increase in the intensity and frequency of heatwaves in every region of the world, according to the IPCC.

However, according to the EM-DAT database (see map above), there were no recorded heatwave disasters anywhere in Africa this year. (In fact, EM-DAT lists no more than two heatwaves in sub-Saharan Africa since the beginning of the 20th century.)

This is despite the fact that many parts of Africa did experience record-breaking heat in 2023 (see: Heatwaves). So, why did these events go unrecorded in the EM-DAT database?

The reason is that, for EM-DAT to record a “disaster”, it requires there to be some record of an impact on people.

In Africa, the impacts of extreme heat on people are not routinely recorded as they are in other continents. For example, there are few reliable records of how heatwaves drive up hospital admissions or lead to cropland being destroyed in Africa, Pinto says:

“Some people call heatwaves the ‘silent killer’ because we can’t see the impacts. It is easy to see flooding and people drowning and to record their deaths. But when it’s a heatwave and we don’t see the impact with our eyes, it’s difficult to record.

“So, if a heatwave happens in, say, October and kills 10 people. We don’t know what caused the death of those people. Probably, it was the increase in temperature, which caused them to go to the hospital and suffer heart failures or strokes, but the people responsible for recording the deaths do not make the association with high temperatures.”

Even when observational data and the impacts on people are recorded for an extreme weather event in Africa, there is a good chance that people living outside of the region or country affected will never hear about it.

This is because there is generally less media reporting on African extreme weather events when compared to events in North America or Europe. (Libya’s deadly floods in September were a noticeable exception to this.)

Understanding the reasons behind this are extremely complex.

One survey of 38 African editors by the nonprofit Africa No Filter in 2021 found that shrinking newsrooms and lack of funds prevented deeper reporting and the positioning of correspondents across multiple countries.

Western media has been criticised by young climate activists for giving more priority to extreme weather events in the global north than in Africa.

Sharelines from this story

Discussion about this post