KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— In the post-World War II era, there have been nearly 200 instances of states voting for one party for president and another for Senate in presidential election years.

— This type of ticket splitting has generally been to the benefit of Democrats, who have been out of the White House for a slight majority of that timespan.

— The split-ticket trend has been declining, but Democrats will want to reverse that to some degree this year.

A history of split presidential/Senate outcomes

In order to hold their Senate majority, Democrats are almost certainly going to have to win at least two and maybe more states that Republicans win at the presidential level. With a current 51-49 majority (including independents), Democrats are already set to lose an open seat in West Virginia, a state Republicans will win at the presidential level in a landslide, and they are defending Sens. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) and Jon Tester (D-MT) in states that also should vote Republican for president.

If Democrats were to be able to hold the Senate and generate more split-ticket outcomes than Republicans, there wouldn’t be anything odd about that historically—in the post-World War II era, there have been 196 split presidential-Senate outcomes over 19 presidential election years. Democrats getting elected in Republican-won presidential states accounted for about 70% of the split outcomes. Only a quarter of the cases featured a Republican Senate candidate winning a state that voted for the Democratic presidential nominee, while the rest of the results included non-major party candidates at either level.

Democrats’ ability to generate these split outcomes was a key factor in their retention of the Senate for much of the second half of the 20th century—that period was defined by Democratic dominance in Congress (Democrats held the Senate for all but four Congresses from 1952-1992) but Republican success at the presidential level (Republicans won 7 of the 10 presidential elections held in that same timeframe). In more recent years, this trend of ticket-splitting dissipated—in both the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections, only one state (Maine in 2020) produced a split presidential-Senate outcome.

What follows is the first of a two-part history of postwar Senate results in elections held concurrently with the presidential election. As you’ll see, the number of split outcomes hit double-digits in nearly every election from 1952 to 2000.

This part will look at elections in the 1948-1980 period. In 1948, Democrats flipped the chamber after a brief two-year GOP majority. In 1952, Republicans regained the majority, but promptly lost it in 1954—they would stay in the minority until 1980. Part two will look at 1984-2020.

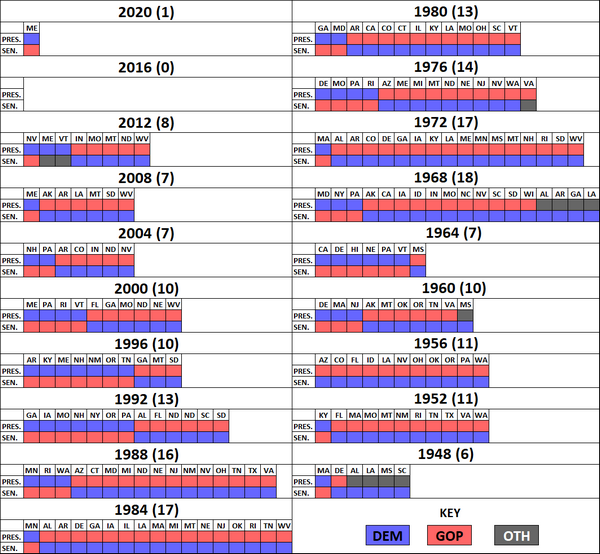

The full list of postwar split-ticket outcomes is shown in Table 1 (you can click on the table to expand it to a more easily readable size).

Table 1: Split presidential/Senate outcomes by year, 1948-2020

Sources: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections, Crystal Ball research, Wikipedia.

1948

As President Harry Truman (D) staged a come-from-behind upset over Republican Thomas Dewey, 1948 was a fairly straight-ticket cycle, at least compared with what would come in subsequent elections.

Democrats, who had just lost control of Congress in the 1946 midterms, regained both chambers. Senators who were up in 1948 last had to face voters in 1942, which was Franklin Roosevelt’s final midterm, and one where his standing with voters had ebbed. Because of that, Republicans went into 1948 holding more vulnerable seats—Democrats defeated 8 GOP incumbents and flipped an open Republican-held seat in Oklahoma. But 8 of the 9 seats that Senate Democrats gained in 1948 were in states that Truman carried.

With that, there were only two “true” crossover states in 1948: Delaware, which went for a Dewey/Democratic combination, and Massachusetts, which was Truman/Republican. In the former, first-term Republican Douglass Buck lost 51%-48% to Democrat Allen Frear. As we’ll see later down the line, though Delaware emerge as a presidential bellwether beginning with the 1952 election, it would frequently produce split ticket results. In Massachusetts, Leverett Saltonstall, a 1944 special election winner who was exactly the type of Yankee Republican that had traditionally thrived in the state, won a full term.

Though Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina are considered crossover states for the purposes of Table 1, they reelected segregationist Democrats to the Senate while backing the like-minded South Carolina Gov. Strom Thurmond on the States’ Rights (“Dixiecrat”) ticket as a protest against Truman.

1952

Republicans captured the presidency for the first time in two decades with Dwight Eisenhower. The Democratic nominee, Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson, carried seven formerly Confederate states and narrowly claimed the Civil War border states of Kentucky and West Virginia. Democratic incumbents were reelected in five Eisenhower-won states, although only one, New Mexico’s Dennis Chavez, was seriously challenged.

More impressively, Democratic challengers defeated Republican incumbents in four Eisenhower-won states. All four victorious Democratic challengers from 1952 would go on to have consequential careers on the national stage: John F. Kennedy in Massachusetts, Stuart Symington in Missouri, Mike Mansfield in Montana, and Scoop Jackson in Washington state.

The sole Stevenson-Republican crossover state was Kentucky, which was also the closest state in the presidential election that year (Stevenson carried it by just 700 votes). Republican John Sherman Cooper, who was ousted in 1948, narrowly defeated an appointed Democrat to return to the Senate (Cooper had a durable career as a legislator and diplomat that ultimately included three tours of duty in the Senate).

1956

At the presidential level, only four states changed hands between 1952 and 1956, as Eisenhower and Stevenson faced each other again. Eisenhower flipped Kentucky, West Virginia, and Louisiana. Meanwhile, Stevenson flipped Missouri, a perpetually close state at the time. None of the three Civil War border states that changed hands—Kentucky, West Virginia, and Missouri—split their tickets in Senate races that year. In Louisiana, which voted for a GOP presidential nominee for the first time since Reconstruction in 1956, Democratic Sen. Russell Long (the son of the famous Kingfish) was reelected without opposition.

Aside from Long, six other incumbent Democrats were elected in Eisenhower-won states: these included both long-serving members, like Arizona’s Carl Hayden and Washington state’s Warren Magnuson, and some newer members, like Florida’s George Smathers and Nevada’s Alan Bible. Democrats defeated Republicans in the Eisenhower-won states of Idaho, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, while winning an open-seat contest in Colorado. Though the Democratic freshmen from this class were, overall, not as notable as the names we mentioned that came out of 1952’s class, Idaho’s Frank Church, who’d become a national figure in the 1970s with his investigations into the Intelligence Community, first won in 1956. Church also helps illustrate the differences between the Senate of the mid-20th century and now—no one would ever expect dark red Idaho to elect a Democratic senator now.

Another factor as to why there was so much ticket-splitting in this era was that the parties were more ideologically diverse. For instance, one of the Democratic victors in 1956 was Frank Lausche in Ohio, a sitting governor who was a conservative Democrat (he would later lose a primary to a labor-backed challenger, future one-term Gov. John Gilligan, in 1968).

There were no Stevenson-Republican crossover seats in 1956.

1960

In 1960, a year that saw the closest presidential election (by popular-vote margin) of the 20th century, most of the ticket-splitting, at least at the senatorial level, was to the benefit of Democrats. Only three of John F. Kennedy’s states, including his home state, elected Republicans, while six of Richard Nixon’s states elected Democrats.

Mississippi, which elected a slate of unpledged electors that cast their electoral votes for segregationist Sen. Harry F. Byrd (D-VA), reelected arch-segregationist Sen. James Eastland (D) in a nearly-unanimous vote. We’re making a bit of a distinction between Alabama and Mississippi. In Alabama, Kennedy won the popular vote but a majority of the state’s electors voted for Byrd. As Alabama reelected Sen. John Sparkman (D), we’re calling it a straight-ticket Democratic state. But in Mississippi, “Unpledged Electors” actually outpolled the major party nominees.

In Delaware, the only crossover seat that actually changed hands, Frear, who was a Dewey-Democrat in 1948 himself, lost to then-Gov. J. Caleb Boggs (R). Without spoiling anything, we’ll just say that Boggs, the next time he was up in a presidential cycle, lost to another crossover senator.

Two notable results, from either side, came in Massachusetts and Tennessee. In Kennedy’s home state, which gave him just over 60% of the vote, Saltonstall remained popular and won what would be his final term. In Tennessee, Sen. Estes Kefauver was Stevenson’s running mate four years earlier. Though Kefauver couldn’t deliver the state in 1956 (in both of his runs, Stevenson came tantalizingly close to carrying the state), he clearly remained popular at home: as Nixon improved several points on Eisenhower’s showing in Tennessee, Kefauver was reelected with over 70%.

1964

After the close 1960 election, the 1964 result was arguably the last truly unambiguous Democratic landslide election. Lyndon Johnson, who ascended to the presidency after Kennedy’s 1963 assassination, faced Arizona GOP Sen. Barry Goldwater. Johnson, who ran as a supporter of civil rights, improved on Kennedy’s showing in most states but cratered in the Deep South.

Given Johnson’s strong showing, almost all of the Senate-level ticket splitting was to the benefit of Republicans. The sole exception came in Mississippi: as Goldwater took close to 90% of the vote there, veteran Sen. John Stennis (D), as was often the case, did not even have a Republican challenger.

The sole crossover state that changed hands in 1964 was a notable one: California. Appointed incumbent Pierre Salinger (D), who previously served as John F. Kennedy’s Press Secretary, was upset by Republican George Murphy—the Center’s Director, Larry Sabato, once took a deeper look at the race and offered some takeaways in Politico Magazine. Elsewhere, traditionally Republican states that defected to Johnson, like Vermont and Nebraska, reelected GOP incumbents while future Republican Leader Hugh Scott narrowly held onto his Pennsylvania seat.

Finally, there was almost some symmetry in the crossover results: Goldwater’s best state (Mississippi) elected a Democrat, and Johnson’s second-best state (Hawaii) elected a Republican—Sen. Hiram Fong (R) took 53% as Goldwater claimed just 21% in Hawaii.

In 1958, Eisenhower registered some of the lowest approval ratings of his presidency, which contributed to a Democratic wave that year. So, six years later, Democrats entered the 1964 cycle holding three quarters (26 of 35) of the seats that were up. With that, they did not have a ton of room to grow—hence why they only netted two seats. We’d also note that, as longtime Almanac of American Politics author Michael Barone posits in his book Our Country, voters’ desire for stability after the Kennedy assassination probably worked in favor of competent Republican incumbents like Fong and Scott.

1968

Unlike his 1960 run, Richard Nixon came out on the winning side of a race where the national popular vote was closely divided. The 1968 election also produced the most split-ticket contests of any cycle in the postwar era.

This was partially due to the South. First, as with 1948, a bloc of several southern states voted for a regional candidate (in this case, George Wallace) while staying loyal to the Democratic Party down the ballot in the Senate races. But then-Vice President Hubert Humphrey was also weak in the South in his own right—the only formerly Confederate state that he carried was Texas, thanks mostly to the influence of his boss, the outgoing President Johnson. As Humphrey placed third in each of the Carolinas, for instance, they both sent Democrats to the Senate.

Outside of the South, Republicans picked up two Humphrey-won states in the Mid-Atlantic with moderate candidates: Reps. Charles Mathias (R, MD-6) and Richard Schweiker (R, PA-13) won promotions, although the former was helped by a split in the state Democratic Party (a conservative Democrat ran as a Wallace-ite third party candidate, taking 13% of the vote).

Democrats, meanwhile, had better luck in flipping open seats. In one of the cycle’s closest Senate results, former Gov. Harold Hughes (D-IA) won an open seat that had been in GOP hands since the 1940s. In California, GOP Sen. Thomas Kuchel lost his primary to a more conservative challenger. The beneficiary of this was former state Controller Alan Cranston (D), who won the Senate seat and would hold it into the 1990s. As an aside, in 1964, Cranston finished a close second to Salinger in the Democratic primary—had he won the nomination, perhaps he’d have been able to keep the seat in Democratic hands. But as it happened, in the 1960s, California elected two crossover senators, of different parties, in back-to-back presidential elections.

One final note on 1968: despite Wisconsin’s image as a swing state (which it certainly is), 1968 was the most recent presidential election where the Badger State actually split its ticket. There is some chance that this streak could end in November. If we had to guess, Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) will probably run ahead of Joe Biden in November, so we could easily see a situation where Biden just barely loses the state while Baldwin wins a third term. Baldwin finally drew a notable challenger, wealthy businessman Eric Hovde (R), earlier this week—Hovde lost a primary to face Baldwin in 2012.

1972

Richard Nixon, as the incumbent, would win a 49-state rout—but he could hardly be bothered to campaign for down-ballot Republican candidates. This showed up in the Senate races: amidst Nixon’s landslide, Democrats netted two seats, winning about half (16 of 33) the seats that were up.

Ironically enough, the sole state that Nixon lost, Massachusetts, was also a crossover state, as it gave liberal Republican Edward Brooke a second term. Another somewhat ironic result was Mississippi: as with 1964, it was the nation’s most Republican presidential state. Veteran segregationist James Eastland, in a bit of a rarity, did have a contested race—the Republican nominee came within 20 points. But Eastland had emerged as a key Nixon ally, so national Republicans did not intervene against him. In this era, where every seat seems to matter, it is hard to imagine this type of disarmament.

In 1972, Democrats picked up two open GOP-held seats and defeated four Republican incumbents. As we alluded to earlier, the most impactful of these flips was in Delaware: now-President Joe Biden defeated the aforementioned Boggs, who reportedly wanted to retire but stayed in the race at Nixon’s behest, by a 51%-49% margin.

Biden, of course, went on to hold his seat for 36 years, but other Democratic gains from 1972 were more ephemeral: they gained seats in Colorado, Iowa, Maine, and South Dakota, only to lose them all when they were next up, in 1978. Still, the Maine result was notable: then-Rep. William Hathaway (D, ME-2) seemed to outwork Sen. Margaret Chase Smith, denying the venerable Republican a fifth term.

1976

Former Gov. Jimmy Carter (D-GA) narrowly prevailed over incumbent Republican Gerald Ford. As with the contest at the top of the ballot, the Senate elections that year were marked by turnover: as the floor leaders from each party retired, a dozen Senate seats changed hands. With that dynamic, it may be a little surprising that 1976 was the first postwar Senate cycle where no crossover seats featured an incumbent losing reelection.

Overall, nine senators were defeated in 1976, but all such cases aligned with the top of the ticket: five Democrats lost in Ford-won states, while four Republicans lost in states that Carter carried.

Instead, the crossover seat changes in 1976 came in open seats. Republicans picked up seats in Carter-won Missouri and Rhode Island with well-known candidates: in the first with former Gov. John Chafee (R), a liberal, and in the second with John Danforth, a two-term state Attorney General. Democrats, meanwhile, flipped Arizona with Pima County (Tucson) Attorney Dennis DeConcini and picked up Ford’s birth state of Nebraska with Omaha Mayor Edward Zorinsky. As we’ll see later on, starting with Zorinsky, Nebraska, one of the reddest states in the late 20th century, would split its ticket for mavericky Democrats with some frequency.

As a concluding thought on 1976, both parties held the seats of their retiring floor leaders—and each came in a crossover state. In Pennsylvania, which Carter carried 50%-48%, John Heinz (R), a suburban Pittsburgh congressman with a recognizable last name, replaced Minority Leader Hugh Scott (R). In Montana, which was part of Ford’s Rocky Mountain regional sweep, then-Rep. John Melcher, who had turned in several crushing performances in the state’s more conservative eastern district, replaced Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D). Montana makes frequent appearances on the split presidential-Senate list, something Tester hopes to continue in 2024.

1980

Even with the differing presidential outcomes of 1976 and 1980—Carter went from prevailing in a close contest to carrying just 6 states—the number of crossover states stayed constant, at 13. Ronald Reagan’s showing at the top of the ticket helped Senate Republicans gain a dozen seats that year, but all except for one flip—in Carter’s native Georgia—came in states that Reagan carried. The only other Carter/Republican state that year was Maryland, where liberal Republican Mathias won overwhelmingly in his final election. Mathias remains the last Maryland Republican to win a Senate race, a fact that popular former Gov. Larry Hogan is trying to change in this year’s open seat race.

Just as Carter’s home state split its ticket, Reagan’s did as well. The aforementioned Alan Cranston (D) was becoming entrenched by this point and drew a weak opponent. The 1980 map featured 10 other Reagan-state Democrats. Republicans made considerable gains in the South this cycle, flipping four states there, but several Democratic heavyweights with personal popularity still won easily: Dale Bumpers in Arkansas, Wendell Ford in Kentucky, and Fritz Hollings in South Carolina. As with 1956, Louisiana’s Russell Long was, on paper, a crossover member, though he deserves a bit of an asterisk. Under the state’s jungle primary system, which it adopted in the 1970s, he won outright in September against state legislator Woody Jenkins—in 1996, Jenkins, as a Republican, almost won a Senate seat, but he was a conservative Democrat in 1980. In any case, given his family name and personal stature, we suspect Long would have been perfectly capable of dispatching a nominal Republican.

The last time the 1980 seats were contested was in the pro-Democratic Watergate cycle of 1974, which created some political whiplash. Colorado’s Gary Hart and Vermont’s Patrick Leahy were both from that 1974 class. Both barely held onto their seats in 1980, and would become important national politicians—the former as a presidential contender, and the latter as the eventual Senate President Pro Tempore. As a brief note, we would recommend Marc Johnson’s book Tuesday Night Massacre, which looks in depth at several Senate races from that cycle.

Elsewhere on the map, Democrats held open seats in Illinois and Connecticut. In the Nutmeg State, former New York Sen. James Buckley, who won on the Conservative Party line in 1970 but was ousted in 1976 as a Republican, was the GOP nominee. In 1976, Buckley lost to Democrat Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who the aforementioned Barone famously called “the nation’s best thinker among politicians since Lincoln and its best politician among thinkers since Jefferson.” In 1980, Buckley ran in Connecticut and lost to Democrat Chris Dodd, who would become the state’s longest-serving senator.

In Part Two, we’ll pick up the story in 1984.

Discussion about this post