Books

Photography

#horses

#Ivan McClellan

#sports

March 3, 2024

Grace Ebert

Rodney & RJ, McCalla, Alabama. All images © Ivan McClellan, courtesy of Damiani, shared with permission

In 1982, Charles Sampson became the first Black man to win the world championship bull-riding competition. Becoming a cowboy was his childhood dream, and despite breaking nearly every bone in his body during his relatively long career, Sampson continued to climb atop the ornery animals and bolt into the arena. Even after an incredibly tough ride, he was known to vault himself off of the bull and land on his feet. He feels, to be cliché, that he was born to ride.

But there’s nothing cliché about Sampson’s story. As he writes in the introduction to the forthcoming book Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture, “Every year there are fewer Black cowboys in America as the population ages, and young Black people believe the western lifestyle isn’t for them.”

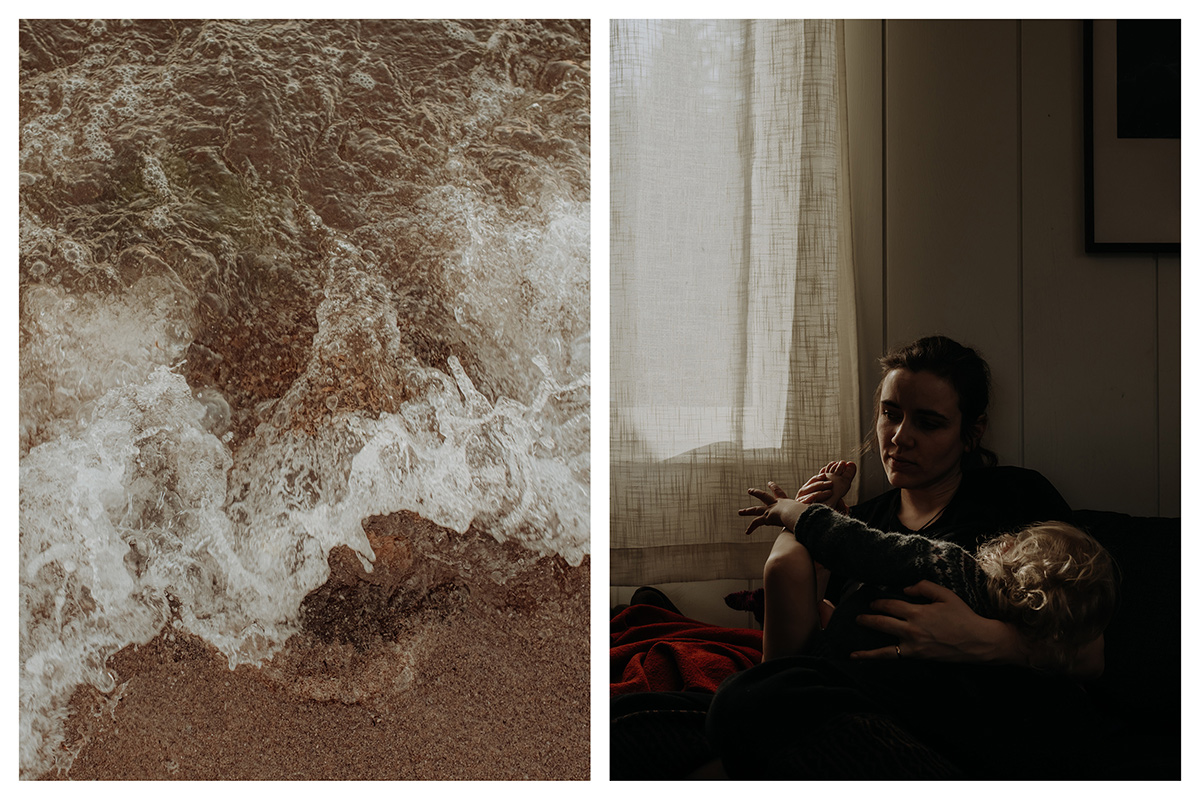

Published by Damiani, Eight Seconds comprises 118 images by Ivan McClellan, a Portland, Oregon-based photographer who’s spent nearly a decade documenting the lives, wins, and losses of the Black rodeo community from Alabama to Los Angeles. He offers an insider’s view, capturing the addictive energy of the sport and the rich sense of camaraderie it fosters.

“I didn’t expect for this work to take over my life and become a passion/obsession for the better part of a decade,” McClellan tells Colossal, sharing a sentiment not unlike that of the people he photographs. “I kept going where I was useful and needed, and this book is a love letter to the culture that has transformed my life.”

Patrick Liddell, Las Vegas, Nevada

The slim volume is packed with a mix of portraits and candid, action shots that evidence the range of emotions within a single day of rodeo life. McClellan visits the teenage sensation Kortnee Solomon at her family’s ranch in Texas and a beaming rodeo queen in Okmulgee. He also photographs the Compton Cowboys, a collective devoted to bettering the lives of inner-city kids through equestrian training. “I’ve stood in front of a charging bull, walked through snake-infested fields, and laid on the ground while horses ran past me all to get a good photo,” he says. “Getting the shot is more important to me than my fear.”

McClellan self-published Eight Seconds in 2022—the title, of course, references the eight wild seconds riders must stay on their animals, one hand in the air, to score points—and the forthcoming edition adds to the original. Together, the photos unveil a firmly rooted ethos of care for both the animals and each other. “I’ve learned that Black cowboys treat you like a family member until you prove yourself unworthy of their trust. Sacrifice is required to live the cowboy lifestyle. I’ve seen cowboys go hungry so they could afford to feed their horse or get their cell phone cut off to pay for rodeo fees,” he says.

Keary Hines, Prairie View, Texas

Eight Seconds comes at a time when Black cowboys are gaining attention, in part because they counteract a White-washed historical narrative. In much of American pop culture, the term cowboy conjures an image not unlike a dusty, gun-toting Clint Eastwood in The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. But the word itself originated as a derogatory alternative to cowhand and was often given to Black men working with cattle. After emancipation, one in four cowboys were Black.

Last spring, an exhibition at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos opened as a corrective to the narratives that center on the White, Americana hero. Spanning pre-Civil War to the present day, the show featured McClellan’s portraits, alongside works by artists like Alexander Harrison and Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe. And in Denver, another recent exhibition devoted itself to expanding the range of perspectives on what it means to be a cowboy.

While visually striking and exuding a warmth and comfort possible only after years of interaction, the photos are effective in part because they challenge these long-held notions about who partakes in the sport and what the rodeo lifestyle looks like in the 21st century. The photographer references the fashion choices emerging from the arena and beyond as a prime example of how Black cowboys both buck stereotypes and harness the independence associated with the archetype. He adds:

To be a Black cowboy is a defiant declaration of self. Going against conventional expectations of Black and White culture requires confidence and a sureness of one’s truth. Fashion is the most obvious way this comes to life. See cowboys riding in gold chains and Jordans, long braids and acrylic nails blends hip-hop culture and the west in interesting and surprising ways.

Eight Seconds, which is edited by Miss Rosen, is available for pre-order on Bookshop. Find a larger archive of McClellan’s work on his site and Instagram.

Marland Burke, Brandon Alexander, James Pickens Jr., Los Angeles, California

Rodeo Queen, Okmulgee, Oklahoma

Dontez & Floss, Okmulgee, Oklahoma

Jadayia Kursh, Okmulgee, Oklahoma

Bull Riders, Rosenberg, Texas

Cover of ‘Eight Seconds: Black Rodeo Culture,’ Damiani Books (2024)

#horses

#Ivan McClellan

#sports

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $5 per month. You’ll connect with a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about contemporary art, read articles and newsletters ad-free, sustain our interview series, get discounts and early access to our limited-edition print releases, and much more. Join now!

Discussion about this post