If you want your child to be a superstar athlete like Shohei Ohtani, a good place to start is to take a look at what his parents did, consciously and unconsciously, to help an ordinary boy become baseball’s biggest attraction.

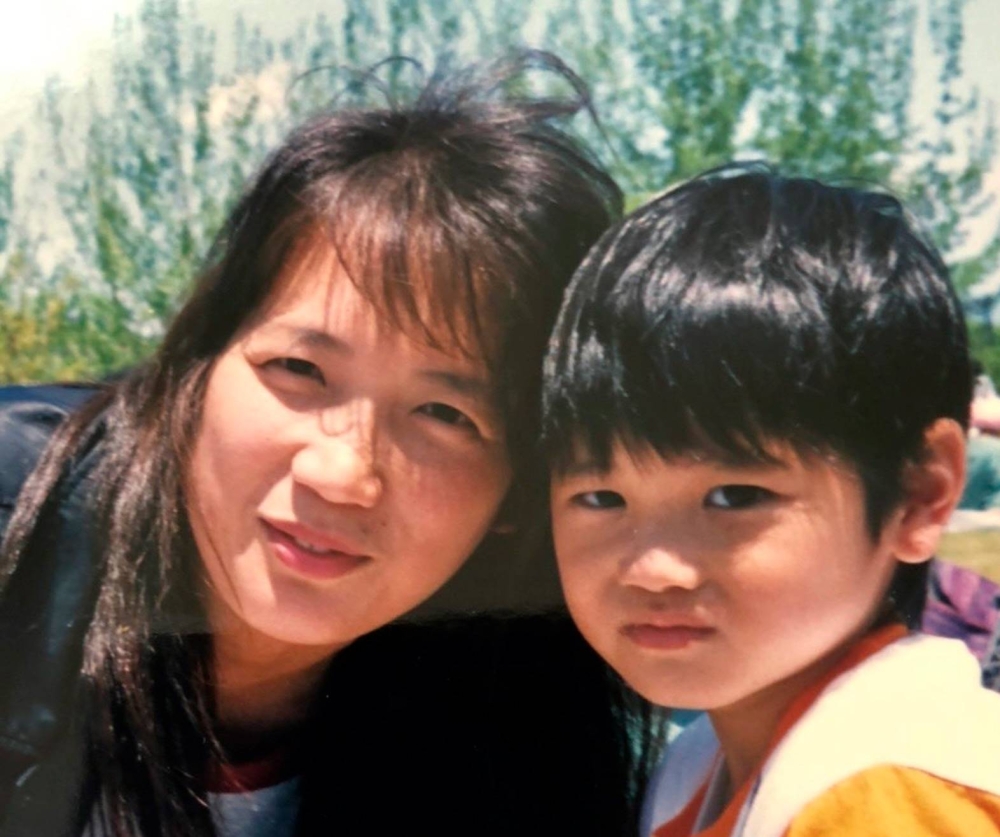

Ohtani’s father, Toru, connected with his son through a shared journal they passed back and forth, while his mother, Kayoko, proudly displayed his sporting memorabilia in the family home.

And the couple, who have two other children, had a parenting rule they swore by: no arguing in front of the kids.

Journalist Taeko Yoshii spent countless hours learning how some of the nation’s top-level athletes were raised and identified a series of commonalities that applied regardless of athletic discipline, gender and family structure.

Yoshii has sat down with 300 mothers and fathers of Japanese pro athletes in their private living spaces and authored two books based on some of those interviews. As she stepped inside the childhood homes of these big names in sports, she noticed all of them have a particular look and feel.

“They radiate the same vibes,” Yoshii said.

“You can tell the moment the door opens, these families put their children first. The majority of the homes I visited were rather humble and not luxurious, but you see signs everywhere that tell you there’s a child in the house — artwork, schoolwork, photos and items like rocks and acorns,” she said.

On Yoshii’s long list of interviewees are parents of MLB stars like Ohtani and Ichiro Suzuki, boxing great Naoya Inoue, former Olympic speedskating champion Hiroyasu Shimizu and former tennis player Ai Sugiyama, who reached world No. 1 in women’s doubles and No. 8 in singles, to name a few.

Yoshii became curious about parental influence on athletic success in the late 1990s with the rise of child prodigies like Tiger Woods, Martina Hingis and later Cristiano Ronaldo. When she saw a similar trend in Japan, she started by exploring the early life of Ichiro, who had his first 200-hit NPB season as a 20-year-old in 1994.

“Until then, there was a general belief that athletes peaked in their late 20s. So I started wondering why these kids were excelling in their sports as teenagers and investigating the effect of family environmental factors on top athletes. Lo and behold, a pattern emerged,” Yoshii said.

Despite the low odds of making it as a professional athlete, a 2011 poll by Play Ground, a website focused on soccer training schools, found that 1 in every 4 Japanese parents wants their child to be a pro athlete.

It is widely accepted that a complex mix of nature and nurture is what makes an elite athlete, with factors like genetics and socioeconomic status being major contributors. But Yoshii said an often overlooked component of success is growing up in a stable home.

“Families keep athletes grounded through their highs and lows. These parents are not the type that live vicariously through their children. They aren’t trying to mold their kids into pro athletes. Their child’s sport is a source of fun and joy for them,” Yoshii said.

“For example, Kayoko Ohtani always took Shohei’s older sister to his baseball games to make sure it didn’t just become a father-son activity. With many of the famous athletes I’ve gotten to know, their sport was a family affair.”

Some other ways the Ohtanis and other parents of pro athletes modeled good sportsmanship are, according to Yoshii: finding time for family meals, making their house a calm haven, valuing having fun over winning, allowing children to take ownership of their experiences and not expecting a financial return on investment from their children’s athletic lives.

Ohtani, who signed a record $700 million, 10-year contract to play for the Los Angeles Dodgers late last year, tried his hand at swimming, badminton and volleyball before settling on baseball. Most of those interviewed by Yoshii opted for a multisport approach, exposing their children to a variety of physical activities and letting them choose which sports to pursue.

Richard Williams shares a laugh with his daughter Venus at Wimbledon in 2012.

| Reuters

While there are famous cases of athletes training in one sport from a very young age for a head start toward stardom, like Woods in golf, Michael Phelps in swimming and Venus and Serena Williams in tennis, the question of early specialization is a controversial one, with research suggesting that playing just one sport year-round can do more harm than good for young athletes.

Ryoko Takemura, a former professional tennis player and associate professor at Sophia University who studies the different pathways to expert performance in sports, said it is not coincidental that parents who raise future pro athletes have a lot in common.

“It takes more than just being actively involved in a child’s athletic life to master the art of sports parenting. It’s also knowing your children’s personality type, creating an environment that encourages curiosity, leaving the coaching to the coaches and supporting their health,” Takemura said.

“My research tells me, aside from genes and accumulated practice time, there’s a huge number of factors that can help athletes reach their potential. To get to the highest levels in sports, some specialize early and some play multiple sports. There are benefits to playing different sports, but one approach doesn’t fit all.”

There simply isn’t a known recipe for how to raise well-rounded elite athletes, but Yoshii’s observations have pointed to a handful of factors that could help. Unsurprisingly, much of it comes down to the parents.

“After speaking to hundreds of parents, I can say for sure that sporting geniuses are made, not born,” Yoshii said.

Discussion about this post