On February 20, Ruslan Ablyakimov was walking in Makhachkala, the capital of Dagestan, with two friends when he was stopped by six young men who proceeded to beat him. “Where did you come here from?” they asked, “You are from Moscow, right? What are you doing here?” Before the men left Ablyakimov, they told him, “You have until tomorrow to get out of here” (Meduza, February 20).

Why did these men choose Ablyakimov to beat up? The answer is straightforward: he was the coordinator of the new Navalny Regional Headquarters in Makhachkala. Following this violent event, Ablyakimov complained that he could not find any space to rent for the headquarters, and he ultimately left Dagestan. He promised that this did not mean the headquarters would not open eventually; but its future is uncertain (Kavkazsky Uzel, February 22).

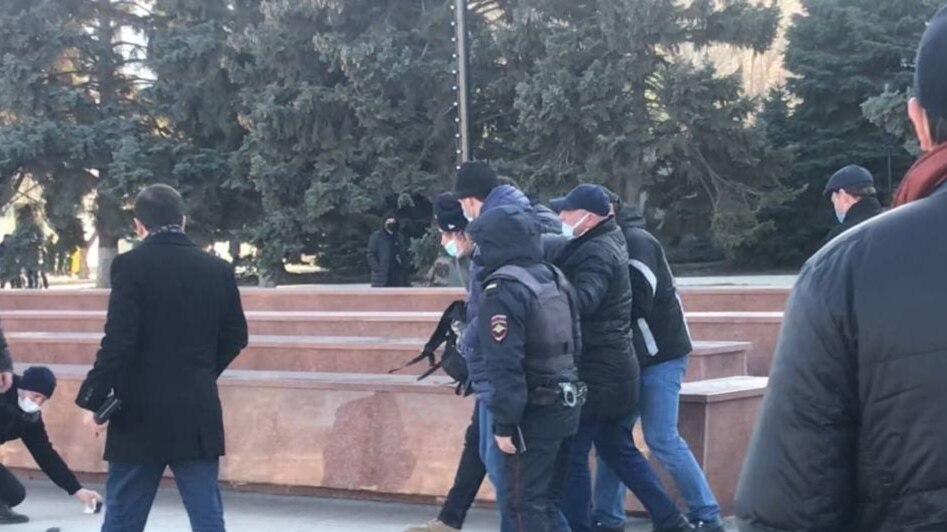

Authorities in Dagestan have not been friendly to supporters of Russian opposition leader and anti-corruption crusader Alexei Navalny in recent months. In late January, protests erupted across Russia, including, on a small scale, in Makhachkala. On January 21, a lone protester was detained by the police with his sign that read “Freedom for Navalny/Freedom for political prisoners” (Kavkaz Realii, January 21). Two days later, over 40 protesters were arrested, including students, in the center of Makhachkala, a city of about half a million (Kavkaz Realii, January 23).

According to journalist Magomed Magomedov, there are two groups of Navalny supporters in Dagestan. The majority of them support his anti-corruption efforts but do not necessarily share his political views; the rest are those who would like to see Navalny as president (Kavkazsky Uzel, January 21). Neither of these groups are particularly large, and videos of protests in Makhachkala show only a small crowd—tens, not hundreds (Kavkaz Realii, January 23).

These protests, which occurred all across Russia, took on a different meaning in the North Caucasus. Indeed, in Makhachkala, protesters frequently distanced themselves from Navalny and said that their actions were in response to dissatisfaction with the authorities in general (Kavkazsky Uzel, February 1). While protests against corruption in the North Caucasus are not an everyday occurrence, there is precedent. In 2017, a few hundred demonstrators came out to support Navalny’s anti-corruption message (Kavkazsky Uzel, June 12, 2017). Earlier, in October 2011, hundreds protested corruption in Makhachkala itself (see EDM, October 12, 2011).

Still, support and turnout for the Navalny protests in particular was low in the region (Kavkazsky Uzel, January 21). So why were authorities so quick to arrest protesters and reticent to allow these actions in the first place? What threat did they perceive? The answer lies not in Makhachkala, but in Moscow. The authorities in the North Caucasus understood that to allow these rallies to move forward would not align with Moscow’s directives to quash any Navalny-related activity, however small the demonstrations may be (Kavkazsky Uzel, January 21). And in the North Caucasus, alignment with Moscow is often vital for regional elites to maintain their power and privilege. Both economically and administratively, Moscow pulls many strings in the region, by appointing outsider governors like Dagestan’s Sergei Melikov and by ordering financial policy in republics like Ingushetia (see EDM, November 16, 2020). In 2014, subsidies to the North Caucasus Republics were all higher per capita than the average in Russia with the exception of Stavropol Krai (Edward C. Holland, “Economic Development and Subsidies in the North Caucasus,” Problems of Post-Communism, December 2015).

The hard line on even limited protests in Makhachkala suggests that any open displays of discontent in opposition to Moscow’s official stance will not be tolerated in Dagestan. At the same time, this implies that Alexei Navalny is likely not the man to mobilize the masses in the North Caucasus, even though some citizens there are sympathetic to his anti-corruption campaign.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tronc/J2FFG2PGIFJWUTNYW5WBVQBWQI.jpg)

Discussion about this post