An archaeological survey has identified traces of hundreds of previously unknown monuments—including five “incredibly rare” prehistoric structures that may have once marked “routes for the dead” into the afterlife.

James O’Driscoll with the Department of Archaeology at the University of Aberdeen in the United Kingdom conducted the survey using LiDAR technology in the Baltinglass landscape of County Wicklow, Ireland, which is renowned for its prehistoric remains. The results have been published in the journal Antiquity.

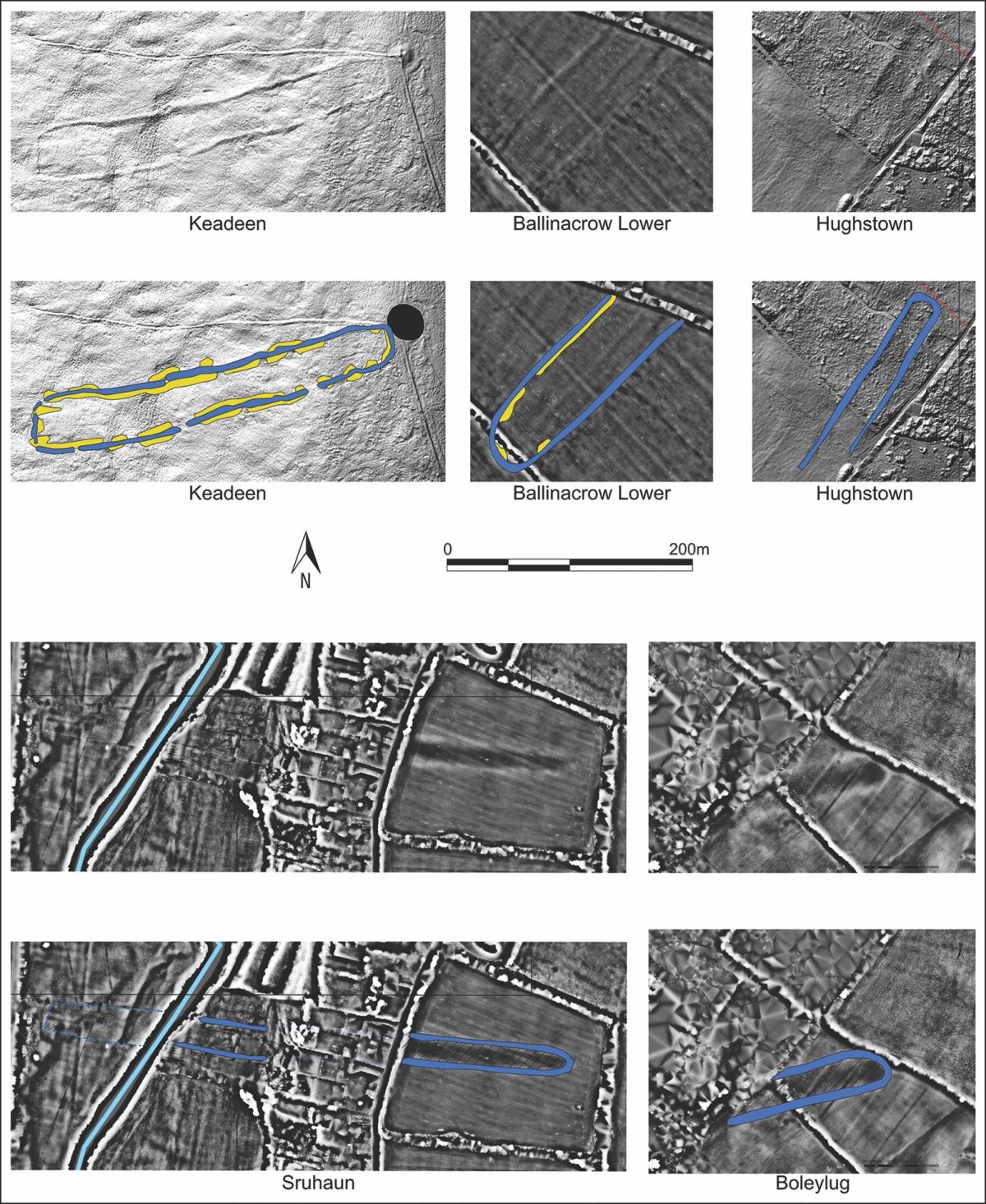

LiDAR is a remote sensing method that involves the use of laser pulses fired at the ground to generate 3D models of a given landscape. This method can map the topography of the land while also revealing hidden man-made features that may not normally be visible.

“I have been working on the Baltinglass landscape for over a decade. It formed the core component of my PhD,” O’Driscoll told Newsweek.

“While my PhD focused on targeted geophysical and remote sensing surveys and excavations, what was sorely missing was a large-scale topographical model of the landscape, which would not only help to knit together all of the research that had previously been undertaken, but also help to discover new archaeological sites that were either hidden under trees and scrub overgrowth, or had been mostly levelled by thousands of years of ploughing,” he said.

James O’Driscoll/Antiquity Publications Ltd

The detailed topographical survey O’Driscoll undertook using LiDAR almost doubled the number of known archaeological sites in the landscape, revealing previously unknown monuments such as a “massive” Bronze Age hillfort, early medieval ringforts and a large number of burial structures from various periods of prehistory.

But the “most significant” findings of the survey, according to the researcher, were a cluster of up five previously unknown “cursus” monuments. These prehistoric monuments, found on the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, are typically long and relatively narrow earthwork enclosures. While poorly understood, they tend to be defined by an enclosing bank with a ditch on the outside. While relatively well-known in Britain, they are poorly documented in Ireland.

“The discovery of the cursus monuments is particularly significant, as these are incredibly rare in Ireland,” O’Driscoll said. “There are less than 20 recorded cursus monuments in Ireland, and they typically occur in isolation or pairs.”

“This makes the identification of five examples in Baltinglass the largest cluster of these sites in the country—but also, the detailed topographical model of the sites and their surrounding landscape provided an opportunity to ‘digitally’ investigate these monuments in detail,” he said.

Using his new data, the archaeologist was able to demonstrate that at least four of the five newly identified cursus monuments were aligned with important solar events. These events were linked to yearly farming cycles, as well as death and rebirth, shedding light on the purpose of these mysterious monuments.

For O’Driscoll, these examples may have symbolized the ascent of the dead into the heavens and their perceived rebirth.

“The function of these types of monuments has always been a thorny topic, as we simply don’t have enough information. But given that some of the Baltinglass sites can also be linked with burial monuments, this suggested to me that they may have been ceremonial monuments used in burial practices, where the cursus marked the physical route in which the dead moved from the living into the afterlife,” O’Driscoll said.

James O’Driscoll/Antiquity Publications Ltd

As well as casting light on their purpose, the cursus discoveries could also help to fill a chronological gap in the settlement record of the area. According to O’Driscoll, the new monuments suggest that the Baltinglass landscape remained an important region for developing farming communities in the region during the Neolithic (or New Stone Age) archaeological period, which in Ireland lasted from roughly 4000–2400 B.C., according to some definitions.

Baltinglass was previously known for its Early Neolithic monuments, as well as those dating from the Middle to Late Bronze Age (around 1400–800 B.C.). However, evidence for human activity and occupation between the Early Neolithic and Middle-Late Bronze Age was almost non-existent, leading experts to conclude that the area may have been abandoned for roughly two millennia.

The latest study may help to challenge this narrative, given that cursus monuments typically date to the Middle Neolithic, although the newly uncovered Irish examples have yet to be comprehensively dated.

“The implications for the study are significant, as it provides an explanation for the function of this monument type in Ireland, and allows us to understand the ritual and ceremonial practices of our ancestors who lived over 5,000 years ago,” O’Driscoll said.

“It is the first focused investigation of this monument type in Ireland, and it provides a platform for future study—key to which will be excavation and scientific dating of these monuments, if we can find the funding!”

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about archaeology? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Discussion about this post