Nearly everyone has experienced the frustration of something you use breaking and being difficult or expensive to fix. Proposed legislation could change that.

It’s been raining on and off all Sunday afternoon but people are lining up outside a building in a corner of Gribblehirst Park in Sandringham, Auckland. In their arms are objects big and small: a Soda Stream machine, a bag full of clothing, a heater, a pair of garden secateurs.

This is a Repair Café, an international movement where volunteers with some kind of fixing expertise get together to provide their services to the community for free. Started in 2009 in the Netherlands, the first Repair Café in New Zealand was in Lyttelton in 2013. Since then, the organisation has grown to operate nationwide, with regular check-ins between different organisers to share ideas, resources and support.

“There are so many products that are made to only last a short period of time; a plastic knob snaps in a kettle, and then the whole thing no longer works,” says Brigitte Sistig, Repair Café Aotearoa’s co-founder. “So many things have been designed to be hard to repair.”

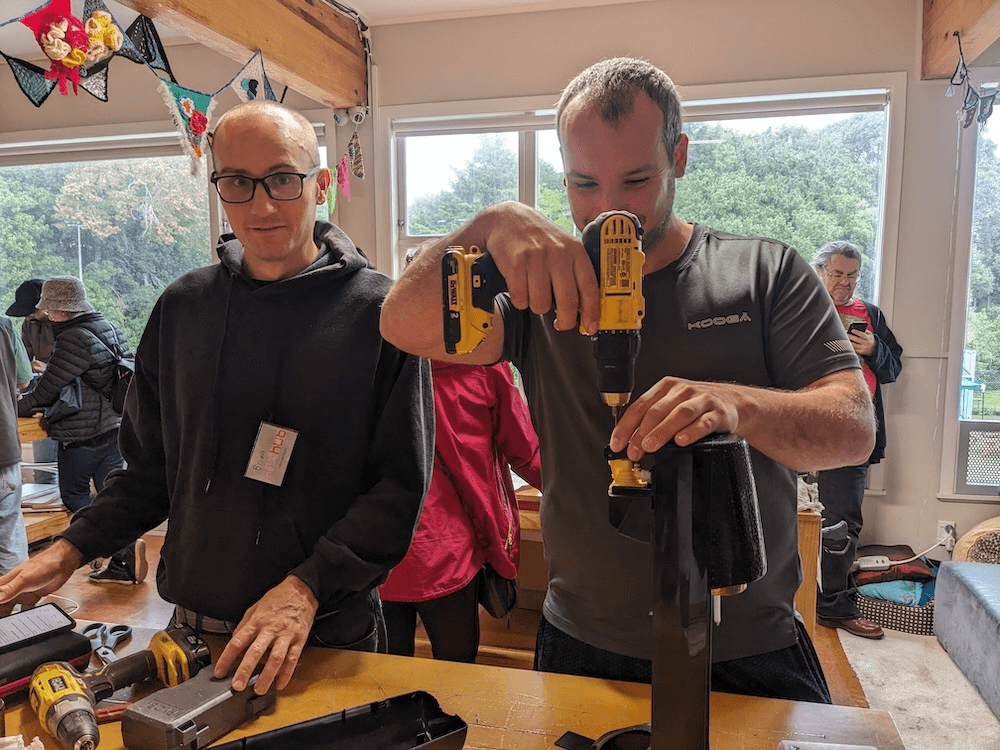

The goal of a Repair Café event is to help identify what can be fixed and teach people how products are designed so they can purchase things that will last longer. While experienced repairers do a lot of the work, key to the process is conversations had with each other to understand what’s gone wrong.

After visitors check in, getting a slip of paper with some details of their repair and what’s needed, they head to different stations. Outside, bikes can get fixed at Tumeke Cycle Space, or woodwork can be repaired at The Shed. Upstairs at Gribblehirst Hub, a shared community space, people can head to a table for sewing and darning, fixing electronics, sharpening knives and tools, and mechanical fixes, requiring glue, drills, screws or nails.

“So many things are built to break – we have entire industries that thrive on the fact that your heater will only work for five years, then you’ll need a new one,” says Jai Singh, the Gribblehirst Hub co-ordinator who is helping to run the Repair Café.

Sidrah is eyeing up the arrangements of tiny allen keys and screwdrivers on the table, putting the awkward bundle of her heater down on the floor while she waits her turn. Its switch has been broken since last winter. “I trained as an electrical engineer, so I know how to fix it, but I just don’t have the tools,” she says. Her overseas qualification isn’t accepted in New Zealand so she hasn’t been working as an engineer – she only heard about the Café through a Facebook ad. She didn’t know that there would be sewing machines available for fixing, and she’s thinking about items of clothing she could bring to fix next time.

What makes it so hard to fix things in New Zealand? As Sidrah found, needing specialised tools is definitely a limiting factor. The Repair Café is able to use their connections to amass the overlockers and sewing machines, drills and awls, whetstones and shoe glue that is required to fix dozens of objects, but almost no-one could have all of this at home. In a culture where it’s perceived as necessary to own a lot of stuff, then it’s inevitable that a lot of that stuff will break down and need repairing.

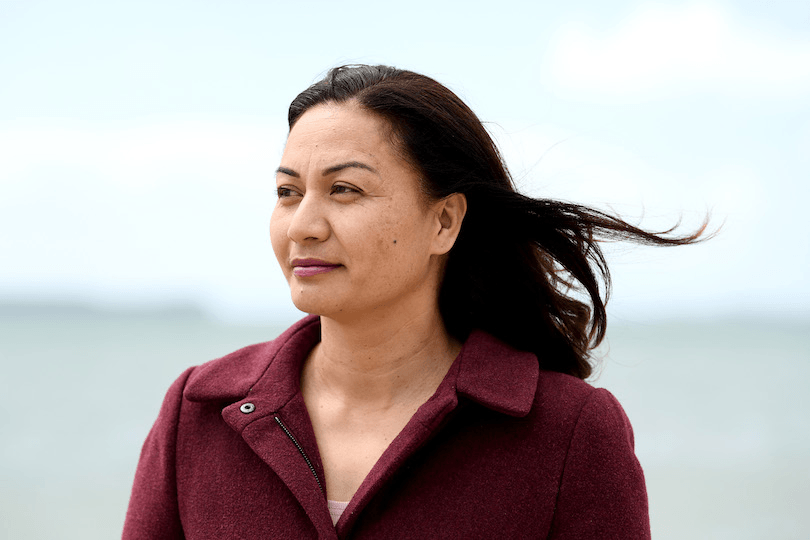

Marama Davidson, Green Party co-leader, knows the satisfaction of being able to fix things, too. “I’ve had a set of drawers for more than 30 years, they’re in my bedroom today,” she says. “I’ve replaced runners, handles and knobs – it could have gone to landfill decades ago but I’ve kept repairing it.” Not everything is this easy to fix: she notes that mass manufacturing means that items are often glued together, or made out of formed plastic that can’t be repaired once it snaps.

“We need it to be easier to replace product parts,” Davidson says. She’s sponsoring a Right to Repair members bill that would update the Consumer Guarantees Act, due to go through parliament soon. It would mandate manufacturers to provide information, software and spare parts for the objects they produce, and give consumers a right to redress if the goods they buy don’t have reasonably available provisions for repair. Repair Café Aotearoa, WasteMINZ and Consumer NZ have long been supportive of a right to repair legislation.

Right to repair laws have been enacted around the world, most notably in the EU: manufacturers are prohibited from creating software or hardware barriers to repair (like preventing the use of 3D printed parts or putting new software on an older device), as well as extended guarantees after an item has been repaired and mandating that information and costs of repairs are easily publicised. US states and the UK also have provisions for repair in their laws. “We’re behind, the rest of the world is pushing for more sustainable consumption,” Davidson says.

Will the law pass? That’s less clear; while in government, Labour ministers Rachel Brooking and David Parker expressed interest in a right to repair law, so they might support one now. Farmers in the US have pushed for a right to repair, specifically regarding agricultural machinery, which New Zealand farmers have also supported; this is an issue that can have broad political support.

At the Repair Café, it’s easy to see how the possibility of fixing things is a “gateway”, as founder Brigitte Sistig puts it. “You come, and you can see how much repairing is possible – you learn how the object works, you learn about waste,” she says. It’s a shift in how to see objects, too, like Sidrah spotting a sewing machine and realising that fabric can be fixed. Wearing out and breaking down is inevitable if something is being used – but that doesn’t mean it has to go straight to the bin. As shoe soles are glued back on, secateurs sharpened, frayed backpack straps reattached, it’s possible to imagine the scene recreated dozens of times around the country, and around the world. Legislation could only make the repairing more easy.

After all, the current way we treat useful objects as disposable hasn’t been around forever. Margaret is 93 years old and has come over from the North Shore for the Repair Café with her daughter. They’re waiting to get their toaster fixed, the guts of the machine exposed on the table as a volunteer examines its glinting metal. “When I was growing up, things were supposed to last forever; I thought it was so wasteful if people chucked their stuff out. But now that’s all people do,” she says. She’s happy that services like this exist. “We need these skills in the community.”

Lai, a woman who describes herself as passionate about knitting and darning, is in the corner of the Repair Café, contemplating the possibilities of repair as she stitches a strap with careful fingers.“I love fixing things, I love knowing that something is mendable,” she says. “But I think that change ultimately needs to come from the top; it shouldn’t be something that you have to choose to come to on your Sunday afternoon, we should just have things that last.”

Discussion about this post