The share of electricity in Great Britain generated from burning coal and gas fell to a record-low 2.4% earlier this month, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

The record low was reached at lunchtime on Monday 15 April and lasted for one hour. There have been a record 75 half-hour periods in 2024 to date when fossil fuels met less than 5% of demand.

There were only five such periods during the whole of 2022 – and just 16 last year.

The findings show that National Grid Electricity System Operator (NGESO) is closing in on its target of running the country’s electricity network without fossil fuels, for short periods, by 2025.

NGESO is “confident” this target will be met, its director of system operations tells Carbon Brief, adding that achieving the goal will be “absolutely groundbreaking and pretty much world leading”.

However, Carbon Brief’s analysis also illustrates some of the challenges to meeting the government’s target of a fully decarbonised electricity grid by 2035.

Fossil fuels fall

The island of Great Britain, comprising England, Scotland and Wales, has its own independent electricity system, which is managed at the transmission level by NGESO.

The transmission grid is effectively the motorway network for electricity.

It links large-scale electricity suppliers such as coal, gas and nuclear power plants to centres of demand, in towns and cities around the country.

Other companies run the low-voltage “distribution” networks, which take power from the transmission grid and distribute it to individual homes and businesses.

For most of its existence, this system had remained largely unchanged for decades. More recently, it has been in the midst of a rapid transformation as part of national efforts to reduce emissions.

In 2009, some 74% of GB electricity was coming from fossil fuels and only 2% was from renewables.

By 2023, there were several thousand large renewable sites dotted around the country, as well as nearly 1.5m small solar installations on the roofs of homes, offices and warehouses.

Only a third of GB electricity in 2023 came from fossil fuels – with 40% from renewables.

Yet these annual figures disguise even greater changes in the month-to-month, day-to-day, hour-to-hour and second-by-second operation of the electricity system.

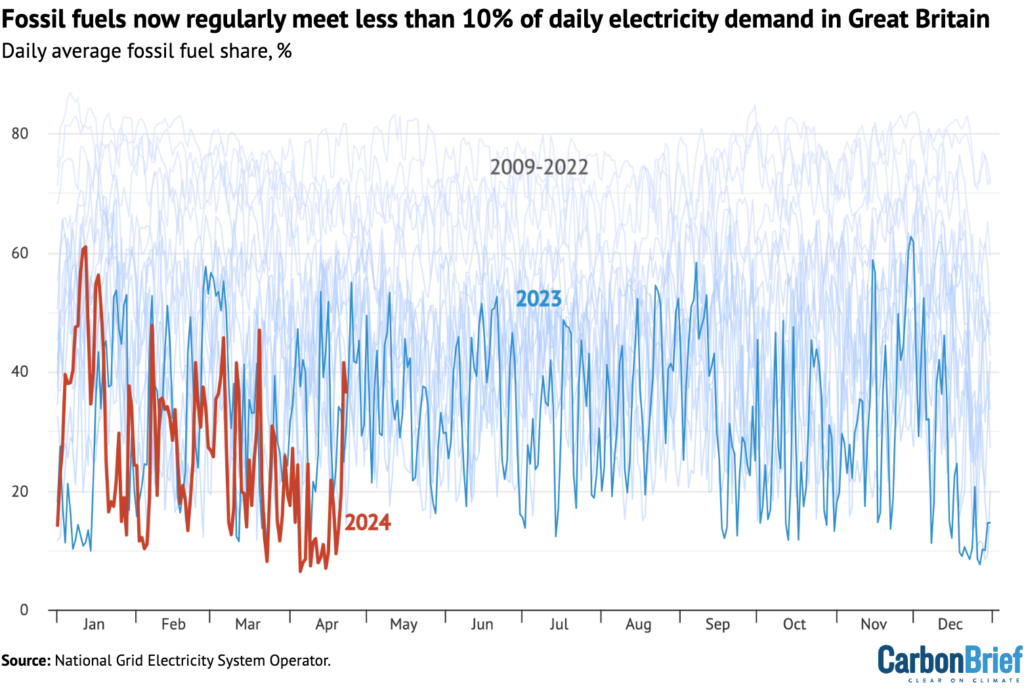

The figure below shows the share of electricity in Great Britain being generated by fossil fuels in each half-hour period since 2009, including the record-low of 2.4% earlier this month.

The figure above shows how unprecedented it is for fossil fuels to be meeting such low shares of demand on the GB grid.

Indeed, the lowest half-hourly fossil fuel share in 2009 was 53% and, as recently as 2018, it had never dipped below 10%. The first half-hour period with less than 5% fossil fuels only came in 2022, when there were five such periods in total across the year.

During 2023, there were just 16 half-hour periods with less than 5% fossil fuels – the majority of which came during December of that year.

In contrast, there have already been 75 half-hours with less than 5% fossil fuels in 2024 to date.

The shift to ever lower fossil fuel use is illustrated in the figure below, which shows daily average shares starting to regularly drop below 10% in December 2023 and April 2024.

The daily average fossil fuel share fell to a record low of 6.4% on 5 April 2024, with the average on 15 April 2024 standing at 7.0%. Until 2022, the daily average had never been below 10%.

‘Zero-carbon operation’

Carbon Brief’s analysis shows that NGESO is closing in on the target, first set in 2019, of being able to operate the grid with “zero carbon”, for short periods, by 2025.

(NGESO defines this target as being able to run the GB transmission grid without fossil fuels. It bases its goal on a metric of 100% “zero-carbon operation”, meaning the share of demand, excluding imports, being met by renewables connected to the transmission grid or nuclear. It says this metric reached a peak of 90% during two half-hour periods in January and March 2023.)

The first-ever period of at least 30 minutes of “zero carbon operation” is most likely to come in autumn 2025, Craig Dyke, NGESO director of system operations tells Carbon Brief. “We’re confident that we will have the right capabilities on the system to be able to do that,” he adds.

Dyke says this moment will be “absolutely groundbreaking and pretty much world leading”, particularly given the size of the GB economy and the fact that, as an island, its grid is relatively isolated from neighbouring countries.

There have been two separate challenges in reaching this target. The first is having enough low-carbon electricity supplies to be able to cover demand during a given half-hour period.

The second challenge is having the technical capability to keep the grid stable without fossil fuels.

These technical requirements include maintaining the frequency of electricity supplies at close to 50Hz and responding to rapid changes in supply and demand through operational reserves.

NGESO also maintains the ability to restart the grid in the case of a total shutdown, sometimes referred to as “black start”, but now more formally called “restoration”.

Increases in wind and solar capacity mean low-carbon sources are now already sufficient to meet 100% of electricity demand in some periods. However, on the technical side, the 2025 target has been a “significant engineering challenge”, Dyke says:

“Getting to the 2025 ambition has been a significant engineering challenge, which we are solving.”

Grid services have, historically, been provided by fossil fuel power plants. Over the past five years, however, NGESO has been changing the way it procures these services, as well as reforming the rules of grid operation and the way it balances the grid in real time.

For example, through its “pathfinder” projects NGESO has contracted a series of sites that can offer grid services without fossil fuels. These include “synchronous condensers”, effectively giant spinning turbines that provide grid stability without burning fossil fuels.

Other key innovations include the use of batteries to manage the frequency of the grid and “grid forming inverters”, which use sophisticated power electronics to offer different types of grid support.

This development means renewable projects will be able to contribute grid stability services, such as “inertia”, that have traditionally only been offered by conventional fossil fuel generators.

Dyke tells Carbon Brief:

“This hasn’t just happened overnight. It’s been a culmination of a significant amount of effort over a number of years. That’s not just us [NGESO] operating in isolation, that’s planning and collaboration with industry, with [energy regulator] Ofgem and with the government…It’s not just about technologies, it’s about hearts and minds and processes and systems and people working together.”

Fully decarbonised grid

For NGESO, the 2025 goal is a stepping stone on the way to being able to run the grid at zero carbon constantly by 2035, in line with the government target of “fully decarbonised” electricity.

(The opposition Labour party is targeting a decarbonised grid by 2030. This target is seen as incredibly ambitious – and possibly even “unachievable” overall. A spokesperson for NGESO tells Carbon Brief: “Our previously published scenarios shows it is achievable – although challenging.”)

There are several further technical challenges to meeting this 2035 goal.

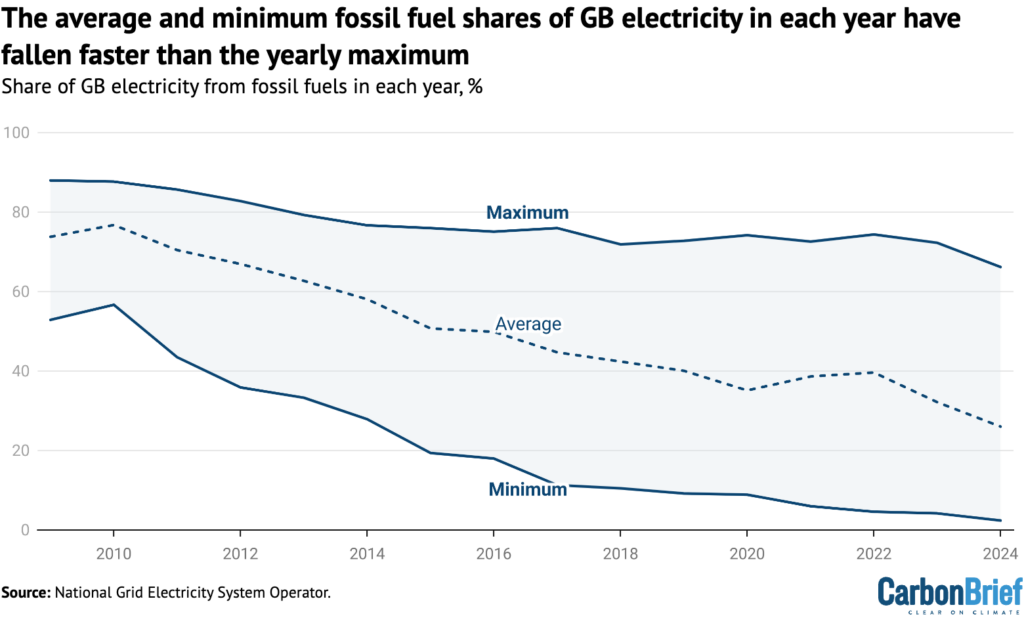

For example, the rise of variable wind and solar has expanded the ups and downs of fossil fuels in the mix, illustrated by the range between peaks and troughs in the first figure, above.

This is illustrated further in the simplified figure, below, by the increasing gap between the highest and lowest fossil fuel shares seen in each year (upper and lower blue lines, respectively).

The figure below also shows the annual average fossil fuel share of electricity (dashed line) falling from 74% in 2009 to 26% in 2024 to date. (The small increase in this annual average in 2022 was due to the GB grid exporting gas-fired power to France, where much of the nuclear fleet was offline.)

Notably, the maximum fossil fuel share in each half-hour period has declined more slowly than the average or minimum figures, falling from 88% in 2009 to 72% in 2023 and 66% in 2024 to date.

This reflects the fact that the GB grid still relies on gas-fired power stations being able to switch on when the wind is not blowing and the sun is not shining.

Crucially, the nation will need low-carbon alternatives to this gas capacity in order to reach the government’s target of a fully decarbonised grid by 2035.

These alternatives will need to operate across a range of different timescales, from seconds through to weeks and even years. For within-day timescales, this is likely to mean expanding energy storage capacity, principally with batteries, but also pumped hydro or compressed air.

For periods of weeks or seasons, the options include ongoing reliance on unabated gas – which would be incompatible with carbon targets – or the use of hydrogen turbines or gas plants that are coupled with carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Sharelines from this story

.jpg?itok=F2C4uk0x)

Discussion about this post