Countries that pump out large amounts of greenhouse gases could “retain or expand” their fossil fuel industries while treating such emissions as “inevitable” in their net-zero accounting, according to a new study.

Some sectors, such as livestock farming and heavy industry, are viewed as particularly hard to decarbonise. This is due, in part, to a perceived lack of cheap technological solutions.

Any “residual emissions” from these practices will have to be balanced by removals from the atmosphere, if nations want to claim they have achieved their net-zero goals.

The new study, published in One Earth, analyses the strategies that nations have submitted to the UN to understand their approach to these emissions, and how they define them.

It finds significant uncertainty, with just 26 out of 71 countries with long-term plans having outlined how much they expect to still be emitting by 2050.

These nations alone say their residual emissions could be up to 2.9bn tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) – equivalent to around 5% of the current global total.

Fossil-fuel producing nations, such as Australia and Canada, plan to continue producing large volumes of emissions – before removing them via carbon capture technologies or paying for them to be offset elsewhere.

The study authors warn that the slow development and rollout of CO2 removal technologies means this approach could lead to net-zero ambitions ending in “failure”.

Hard-to-abate?

“Residual” emissions are defined as those that remain once a nation, or some other entity, has gone as far as it thinks is possible to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

The concept is closely tied with the net-zero targets that many nations have set for the middle of the century. A country must remove CO2 from the atmosphere that is equivalent in volume to its residual emissions, in order to say it has reached net-zero.

The amount of residual emissions each country is left with therefore dictates how much it will have to invest in CO2 removal – either by planting trees or building machines that directly remove the CO2 from the atmosphere.

So far, countries have shown very little progress in developing technologies to remove CO2.

Yet, as the new study explains, “there is a tendency to treat residual emissions as inevitable”. One key reason for this is that these emissions are expected to largely come from so-called “hard-to-abate” sectors.

These sectors are generally framed as those that lack cheap and widely available technologies to drastically cut their emissions. Examples include steel production, aviation and many aspects of livestock agriculture, such as rearing cows, growing rice and using fertilisers..

Yet, despite these common framings, in practice, both residual emissions and hard-to-abate sectors remain poorly defined. Moreover, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that even “hard-to-abate” sectors can feasibly be decarbonised using available technologies.

According to Prof Naomi Vaughan, a climate change researcher at the University of East Anglia (UEA) and one of the new study’s co-authors, this means “net-zero can hide a multitude of sins”. Speaking to Carbon Brief, she asks:

“What are you choosing – as an industry or as a country – to decide is hard to abate…And what genuinely is?”

In order to interrogate this, the team led by Harry Smith, a UEA PhD student focusing on the role of CO2 removal in climate policy, set out to understand what different countries were describing as “residual emissions” and how they were justifying this description.

Big residuals

Under the Paris Agreement, nations are encouraged to submit long-term low-emission development strategies (LT-LEDS). If a country has a mid-century net-zero target, this document will explain how it intends to get there.

In their study, Smith and his colleagues analyse every LT-LEDS submitted to the UN by October 2023 – covering a total of 67 countries. They also include four extra long-term strategies produced by EU member states, but not submitted to the UN.

The 71 nations with long-term strategies for tackling climate change cover 71% of global emissions, the study notes.

However, the majority – 41 in total – do not quantify residual emissions at all in their plans. These include major emitters with net-zero targets, such as China, India and Russia.

The researchers identify 26 countries that have calculated the amount of emissions they expect to still be producing at the point they reach net-zero.

In total, this amounts to between 2.6-2.9GtCO2e, excluding emissions from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF). (The range results from countries including several different scenarios in their strategies.)

The study also compares the scale of each nation’s residual emissions to the highest level its emissions have reached in a year. If countries are yet to peak, data from 2021 was used.

The authors conclude that, on average, the 16 developed “Annex I” countries assessed in this study plan on still producing 21% of their peak emissions when they reach net-zero.

Meanwhile, the nine developing and emerging “Annex II” economies expect to continue producing 34% of their peak emissions, the study finds. This estimate excludes Cambodia, which plans to keep increasing its emissions but cancelling them out by turning its extensive forests into a net carbon sink.

The chart below shows residual emissions (red) as a share of each nation’s peak emissions (blue) – or its most recent annual emissions, if its emissions have not yet peaked. Residual emissions from the US alone are set to be higher than the total emissions of nearly every other country.

Justifying emissions

To understand more about how governments justify the residual emissions in their strategies, the researchers analyse the sectors where emissions remain high out into the second half of this century.

Overall, agriculture is expected to see the least progress in emissions reductions, contributing roughly one-third of residual emissions across all the nations assessed, the study finds.

Methane from livestock and emissions from fertilisers are frequently cited as some of the “hardest-to-abate”. Developed countries only expect their agricultural emissions to drop 37%, on average, by the time they hit net-zero.

(International aviation and shipping, while viewed as some of the hardest sectors to decarbonise, are simply excluded from most countries’ long-term plans, meaning they do not feature prominently in this analysis.)

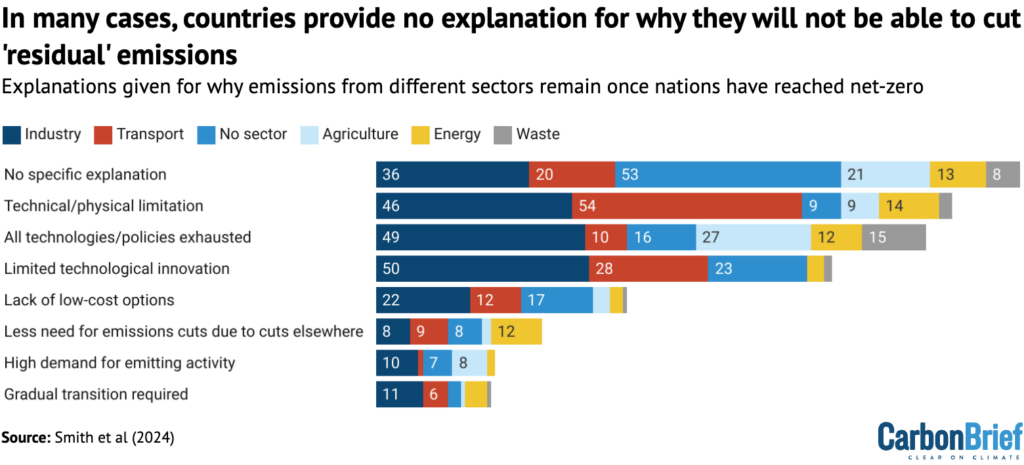

The researchers also look in greater depth at the rationales given by each country for defining emissions as “residual” or “hard-to-abate”, by analysing 357 statements on the topic within the long-term strategies. They group the statements into different categories, based on which sectors are described and the type of language used.

As the chart below shows, countries frequently provide no justification at all for their continued production of residual emissions in particular sectors.

The definition of “residual” varies considerably between countries, with governments focusing on different aspects depending on their circumstances. Smith tells Carbon Brief:

“What you find is this range of rationales [that are] not just technical…They’re not just political either…It’s a kind of pick your buffet of rationales.”

The most common arguments concern residual emissions from industry and transport – particularly the production of cement and steel, the emissions of F-gases and domestic aviation and shipping. (The researchers note a “mismatch” here, with arguments explaining residual emissions from agriculture often overlooked, despite it being the largest contributor.)

Countries most frequently cite the lack of new technologies and limits to existing ones as the reasons for continued emissions from these sectors.

Despite these assertions, hundreds of industry leaders from the heavy industry and heavy-duty transport sectors have described net-zero goals as “technically and financially possible by mid-century”.

For example, a recent report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) concluded that “the technologies to decarbonise hard-to-abate sectors have seen significant progress in recent years and are today largely available”.

‘Retain or expand’

The large amounts of residual emissions in most nations’ long-term strategies reveals that many are expecting to lean heavily on carbon removal to meet their net-zero targets, the study says.

The study notes that this “risks the credibility of their target[s] and risks a failure to meet national and global net-zero”, given the known limits to carbon removals.

In some cases, this could also mean shifting responsibility elsewhere by purchasing carbon offsets from other countries.

Moreover, the study adds that some nations “may attempt to retain or expand their fossil fuel production”, and pass off resulting emissions as “residual”. Vaughan explains that countries may lean towards looser definitions of residual emissions, if it benefits them:

“If you have a country with a very significant investment in the fossil fuel industry or extraction industries, then there is an incentive to imagine getting to net-zero where you still have quite a lot of emissions – but you’re using lot’s of CO2 removal to get there.”

The authors highlight Australia and Canada, two nations that currently produce large amounts of fossil fuels. Both include scenarios in their net-zero strategies – albeit at the high end of several potential outcomes – where emissions only fall by around half by 2050.

In Australia’s case, this scenario relies on purchasing large amounts of carbon offsets from other countries. Canada relies on very high use of CO2 removal technologies.

Prof Holly Jean Buck, a climate researcher at the University of Buffalo who published an initial investigation into residual emissions in countries’ LT-LEDS last year, but was not involved in this research. She says tackling the “ambiguity” around these emissions is key:

“We don’t know if countries are planning to phase out fossil fuels…We have infrastructure that has long lifetimes in terms of how long it takes to build it and how long it will be in operation. Without specificity around which sectors or activities we hope to fully decarbonise and electricity, it’s hard for countries to do that planning.”

More political

Experts tell Carbon Brief the new study is a welcome contribution to a relatively sparse literature on residual emissions.

Buck says it is a “thorough and careful” study that expands on her work, both by increasing the number of strategies assessed and broadening the scope of the analysis.

Her assessment only focused on high-ambition strategies for LT-LEDS from Annex I countries. The new research led by Smith and his colleagues includes a broader range of scenarios, and suggests that residual emissions could be even higher in 2050 than thought.

The study proposes a number of measures to tighten the definition of “residual” emissions and help countries better address them. This includes stronger reporting requirements for national strategies.

The researchers also propose separate targets for emissions reductions and CO2 removals, in order to prevent countries continuing to burn fossil fuels while simply pledging to remove emissions.

Dr William Lamb, a researcher at the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief he supports this idea and adds:

“I would also like to see the discussion of residual emissions become more political than it currently is. If countries were asking questions such as ‘how fast can we phase out fossil fuels?’ and ‘what human needs and services do we need to deliver, at minimum impact to the climate?’ then their long-term strategies would look very different.”

Sharelines from this story

%20(2)%20(1).jpg)

Discussion about this post