The UK government’s spending on climate aid reached its highest-ever level last year, with more than £1.8bn channelled into projects aimed at cutting emissions and boosting resilience in developing countries.

The new data, released to Carbon Brief via freedom-of-information (FOI) requests, reveals how “international climate finance” (ICF) was dispersed in the financial year 2023-24. This builds on larger Carbon Brief analysis tracking ICF spending back to 2011.

UK aid money was, for example, used last year to reconstruct low-carbon power supplies in Ukraine, support flood victims in Pakistan and help Ethiopians facing drought. There were also large contributions to international programmes, such as the Green Climate Fund.

However, despite the record sum, Carbon Brief has identified at least £199m – or 11% – of this money as the result of the government loosening its definition of “climate finance”. This allows the UK to meet its climate-aid targets without providing as much new money.

Carbon Brief understands that this figure is likely an underestimate, because the “provisional” figures provided do not include some of the reclassified humanitarian aid identified in internal documents revealed by a previous FOI request.

Climate finance will be the critical issue at the COP29 UN climate negotiations in Baku, Azerbaijan, later this year. Rich nations are under pressure to increase their overseas climate spending despite many, including the UK, drastically cutting their aid budgets.

Yet, with a general election on the horizon, neither the Conservatives nor their Labour opposition have expressed interest in returning the UK’s aid spending to its previous levels, for the time being.

New record

In 2019 the UK government, led by then-prime minister Boris Johnson, committed to spending £11.6bn on ICF between the financial years of 2021-22 and 2025-26.

This money is the UK’s contribution towards a broader Paris Agreement commitment by developed countries to provide financial support for climate action in developing countries.

Current prime minister Rishi Sunak has reaffirmed this pledge, stating that it is the “right thing to do”. Yet the target has come under considerable strain during his leadership.

In his role as chancellor in Johnson’s government, Sunak announced major cuts to the foreign aid budget – breaching a legal obligation. The government has spent much of the remaining budget on housing refugees, making it even harder to scale up climate spending.

Towards the end of 2023, the government announced that it was broadening its definition of “climate finance”. This allows the UK to stay on track for its pledges without providing as much new money. (See: Accounting changes.)

However, the trajectory the government mapped out to reach £11.6bn still requires annual spending to more than double within five years.

According to the annual figures provided to Carbon Brief, ICF spending reached at least £1.82bn in 2023-24 – an increase of £192m since the previous year. As the chart below shows, this suggests that the UK’s ICF spending will still have to increase significantly over the next two years to stay on track for the £11.6bn goal.

These figures are based on FOI responses from the three major departments responsible for the UK’s overseas climate-related development projects: the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO); the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ). The FCDO is by far the largest contributor, with responsibility for 79% of the ICF spending.

In fact, the total ICF spend in 2023-24 is likely to be at least a little higher than the £1.82bn suggested by the FOI data. According to the government, these numbers are “provisional” and “subject to year-end accounting and audit adjustments”.

This could explain why many of the humanitarian aid projects that were recently reclassified as ICF – as per a previous FOI request by Carbon Brief – do not appear in the data. If these projects are included, they could add tens of millions to the total.

Moreover, Carbon Brief has not been able to obtain data on a handful of “research and innovation” projects that support scientific research in developing countries, which have recently been transferred from DESNZ to the Department for Science, Innovation & Technology (DSIT).

Last year, these projects contributed £7.77m in ICF – amounting to around 0.4% of that year’s total. (Carbon Brief has asked DSIT and FCDO about these projects, but had not received a response at the time of publication.)

Accounting changes

The government has described the £11.6bn goal as “dedicated ring-fenced funding that is distinguishable from non-climate [aid]”. This aligns with the widely held notion that climate finance should be “new and additional”, namely, on top of existing aid programmes.

Nevertheless, in October 2023, the government made three major changes to its ICF accounting in order to inflate its overseas climate spending figures.

The biggest change was including a cut of “core” UK contributions to development banks, such as the World Bank. It also increased the share of British International Investment (BII) input – through which the UK invests in overseas businesses – that counts as ICF.

The third change was labelling 30% of all humanitarian aid provided to the most climate-vulnerable nations as ICF. This applies even if a project has no explicit link to climate action.

In addition, civil servants were tasked with “scrubbing” existing aid projects for any other money that could be counted as ICF, in order to increase the numbers further.

FOI documents released to Carbon Brief earlier this year revealed the details of £1.7bn in funds that the government planned to reclassify as ICF between 2021-22 and 2025-26.

The new data for 2023-24 confirms some of these details. Carbon Brief has identified at least £199m, including funds confirmed separately from the FOI request, which can be attributed to these changes in that year. These figures are “provisional” and may not account for all the changes that have taken place.

The FOI data includes £153.5m that was provided to the BII “programme of support” for companies in Africa, south Asia, the Indo-Pacific region and the Caribbean. Based on a comparison with previously obtained documents, this suggests the UK counted an additional £69.5m of BII investment as ICF in 2023-24, compared to its pre-revision plans for the year.

Carbon Brief could only identify three purely humanitarian projects, contributing a relatively small £4.5m of ICF in 2023-24. This is far less than the £74m identified in government planning documents, previously released to Carbon Brief.

A notable omission from the FOI data is any new funding for multilateral development banks (MDBs), which is expected to make up the biggest chunk of the recently reassigned ICF.

However, the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) confirmed to Carbon Brief that, in fact, some MDB funding was included in the UK’s ICF totals last year. Specifically, £48m of contributions to the 16th “replenishment” of the African Development Fund – part of the African Development Bank – has been classed as ICF.

ICAI has also previously confirmed that, according to an internal government document, £77m was “scrubbed” from existing funds and added to the 2023-24 total. (Carbon Brief was not able to identify which projects these came from, based on the FOI response.)

The government has previously argued that their changes to ICF accounting are in line with the methodologies used by other wealthy countries. In response, development experts have said that the UK should be upholding high standards, rather than lowering them to align with others.

At COP29 in November, rich countries will be under pressure to increase the amount of climate finance they provide to developing countries, in particular via a mechanism known as the “new collective quantified goal”. There will also be discussions at the summit in Azerbaijan of establishing tighter guidelines for what counts as climate finance.

With the UK general election taking place next month and Sunak’s Conservative government likely to lose power, the current polling suggests that the opposition Labour party will be leading the country during the key climate finance discussions at COP29.

Labour has not committed to restoring the UK’s foreign aid budget to its former level, in the short term, and neither has it explicitly committed to maintaining the £11.6bn target.

Major recipients

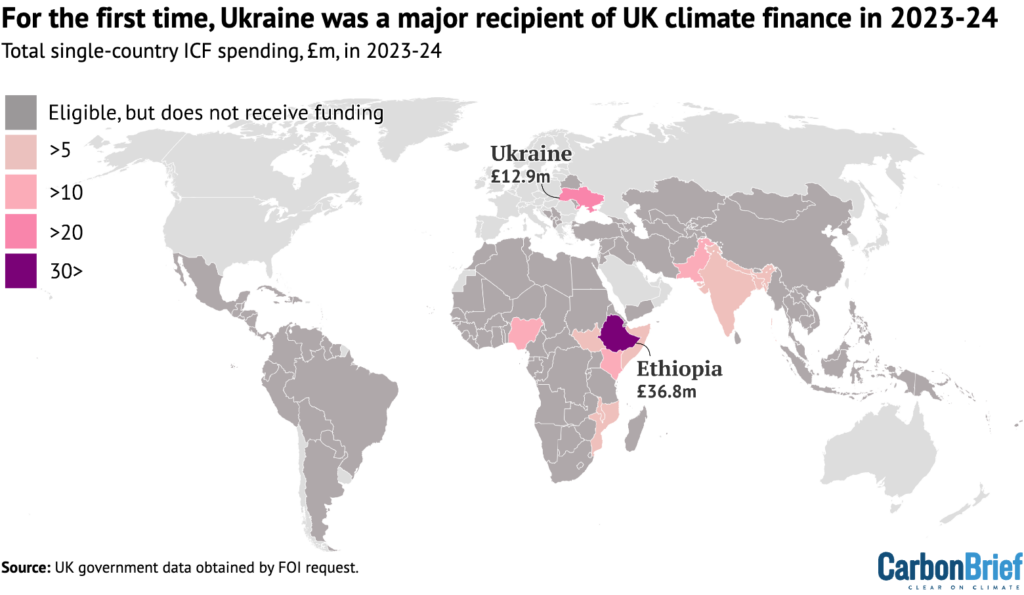

For the first time in the history of the UK’s ICF programme, the government directly contributed climate aid to Ukraine in 2023-24, as part of a wider package to support the war-torn nation.

The UK committed £12.9m of bilateral climate funds towards the Ukraine Resilience and Energy Security Programme – part of a wider £62m package of grants out to the end of 2025 to ensure the “continued operation of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure”.

The first stages of the project focused on immediate repairs and maintenance of the country’s gas and electricity system, including the provision of fossil-fuel generators.

However, the project is also focusing on “pivot[ing] towards rehabilitating infrastructure in a green and energy efficient manner”. This includes money to support renewables, green hydrogen and insulation for homes.

The only country that received more direct, country-to-country ICF funds from the UK last year than Ukraine was Ethiopia. It received £36.8m in bilateral funds, meaning it retains its long-running position as the biggest single-country recipient of UK climate finance.

The east African nation has also been facing significant instability over the past year, as conflict continues following war in the northern Tigray region. Meanwhile, swathes of the country have been struggling with climate change-driven drought.

As the map below shows, much of the remaining bilateral ICF last year went to former colonies in Africa and south Asia, with which the UK continues to foster close relationships. Of the top 10 recipients, seven are members of the Commonwealth association of nations.

Other notable single-country ICF beneficiaries include Pakistan, which received £10m – including £3.3m to help build climate resilience for communities struck by devastating, climate change-driven floods.

Kenya was also a key recipient, with £10.5m to support climate-resilient cities and provide cash transfers to people in drought-affected areas.

Most of the UK’s biggest contributions were to well-established multilateral climate funds and schemes, including a £411m contribution to the first replenishment of the Green Climate Fund. This alone was roughly a quarter of all the climate finance provided last year.

Other major contributions to international efforts in 2023/2024 included a £134.4m injection into the eighth replenishment of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and £44.1m for the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Resilience and Sustainability Trust. The latter is a recently established vehicle for lending to help developing countries prepare for crises.

Developing countries say they need trillions of dollars in annual support to achieve their climate targets under the Paris Agreement, with a preference for grant-based finance. Some wealthy countries have argued that such levels of funding are only possible if a wider selection of countries contribute and there is more emphasis on private-sector funding.

All of these issues will come to a head at COP29 in November, where countries will decide how best to mobilise climate finance in the coming years.

Sharelines from this story

Discussion about this post