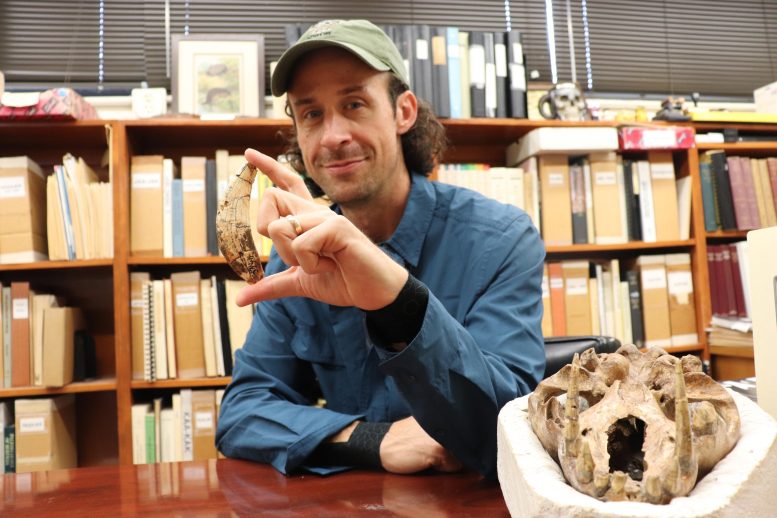

Jackson School of Geosciences doctoral student John Moretti holds a skull of the saber-toothed cat Homotherium that is part of the Jackson School’s Vertebrate Paleontology Collections. Credit: Jackson School of Geosciences

A small, “ugly” fossil unearthed in Texas has been identified as a Homotherium, expanding our understanding of this prehistoric cat’s geographic range and its ecological impact.

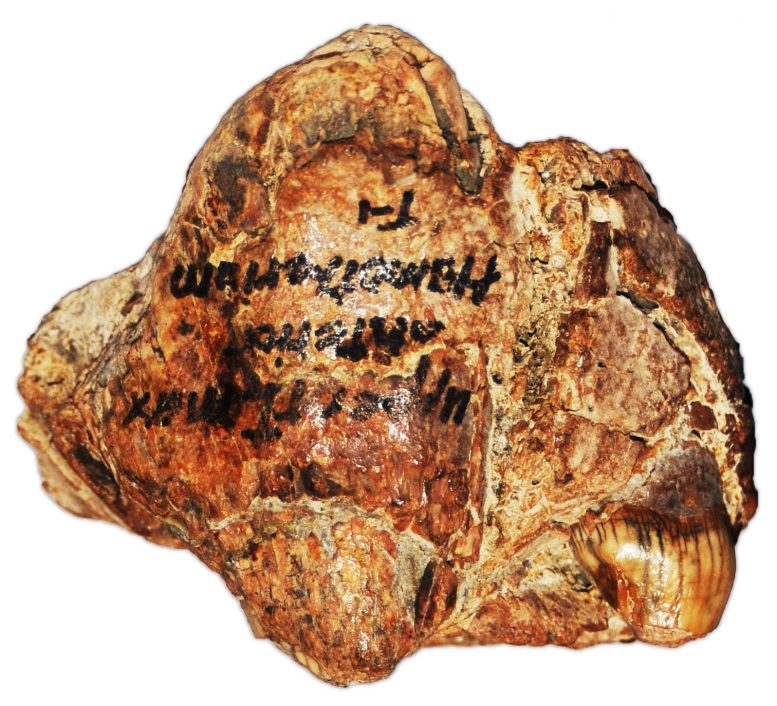

Scientific discoveries don’t always come in the most spectacular forms. Sometimes, they are made from seemingly unremarkable objects, such as a small, nondescript rock. This was precisely the case with a 6-centimeter-wide (2.3 inches) mass of bone and teeth, which played a pivotal role in expanding the geographic knowledge of a large prehistoric cat. This fossil was studied by a team of researchers led by John Moretti, a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, who revealed its significance. The research was recently published in The Anatomical Record.

In the fossil specimen that is the subject of this research paper, two teeth are visible breaking out at the bottom: an incisor, and the tip of a partially-erupted canine. The scale bar at the top right of the image is 1 centimeter. Credit: Sam Houston State University

Unveiling Hidden Details

“You can’t even tell what it is, let alone which animal it came from,” explained Moretti. “It’s like a geode. It’s ugly on the outside, and the treasure is all inside.”

The fossil, appearing as a lumpy, rounded rock with a couple of exposed, worn teeth, had been shaped by its time on the Gulf of Mexico’s seabed before washing ashore. X-ray analysis at the Jackson School’s University of Texas Computed Tomography Lab exposed an additional, hidden canine tooth within the jawbone, unerupted and preserved.

A skull from the saber-toothed cat Homotherium that is part of the Jackson School of Geosciences’ Vertebrate Paleontology Collections. Credit: Jackson School of Geosciences

This crucial find allowed Moretti to identify the fossil as belonging to Homotherium, a genus of large cats that lived for millions of years across continents. Because this specific cat wasn’t fully grown when it died, its distinctive saber-like canine tooth had not fallen into its permanent position. Nestled inside the jaw, the tooth was protected from the elements.

“Had that saber tooth been all the way erupted and fully in its adult form, and not some awkward teenage in-between stage, it would have just snapped right off,” Moretti said. “It wouldn’t have been there, and we wouldn’t have that to use as evidence.”

An artist’s rendering of what a Homotherium could have looked like. Credit: Sergiodlarosa, Wikimedia Commons

Insights into Prehistoric Ecology

Homotherium spanned across habitats in Africa, Eurasia, and the Americas. It was a large, robust cat about the size of a jaguar, with an elongated face, lanky front legs, and a sloping back that ended in a bobtail. Their serrated canine teeth were covered by large gum flaps, similar to domestic dogs today.

Their fossils have been found in several areas of Texas, but this fossil shows for the first time that the big cat roamed the now-submerged continental shelf that connects Texas and Florida. Scientists hypothesize that this stretch of land was a Neotropical corridor. Animals such as capybaras and giant armadillos that wouldn’t have ventured farther north used this strip of humid grassland to move from Mexico to Texas to Florida.

A canine tooth belonging to the saber-toothed cat Homotherium that is part of the Jackson School of Geosciences’ Vertebrate Paleontology Collections. Credit: Jackson School of Geosciences

The discovery that Homotherium lived along this corridor gives scientists a small glimpse into the ecology of this landscape during the Late Pleistocene, Moretti said. Big carnivores such as these cats helped shape the broader animal community, tamping down prey-animal populations and influencing regional biodiversity.

Historical Contributions and Continuing Research

The fossil specimen was discovered more than 60 years ago on McFaddin Beach, south of Beaumont, by Russell Long, a professor at Lamar University, but was donated by U.S. Rep. Brian Babin, a former student of Long’s who worked for 38 years as a dentist. Babin said that his training in paleontology and dentistry helped him recognize that what seems like a strange rock at first glance is actually an upper jaw bone and teeth.“Without question, my professional knowledge and what I’ve learned as a dentist helped me in that regard,” he said.

Jackson School of Geosciences doctoral student John Moretti holds a canine tooth from the saber-toothed cat Homotherium that is part of the Jackson School’s Vertebrate Paleontology Collections. Credit: Jackson School of Geosciences

The research is part of a larger initiative on McFaddin Beach fossils started in 2018 by William Godwin, curator at the Sam Houston State University Natural Science Museum and a co-author of the study. The research was funded by UT, Sam Houston State University, and DOI: 10.1002/ar.25461

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d1/82/d18228f6-d319-4525-bb18-78b829f0791f/mammalevolution_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post