Immune signatures in the blood may flag if someone has ovarian cancer up to four years earlier than conventional methods used to diagnose the disease, new research suggests.

Ovarian cancer is one of the deadliest cancers, with a five-year survival rate of less than 51%. Around 70% of ovarian cancer patients have high-grade ovarian cancer (HGOC), in which cancerous cells look particularly abnormal and are more likely to grow and spread than low-grade cancers.

As with many cancers, early diagnosis and treatment — such as with surgery and chemotherapy — are key to longer survival. If this type of cancer is localized — that is, limited to the ovaries or the fallopian tubes — around 93% of patients are expected to survive for five or more years after diagnosis.

Unfortunately, most patients are not diagnosed with HGOC until the cancer is at an advanced stage, meaning it has spread to somewhere else in the body. In these cases, the five-year survival rate may be as low as 31%.

Related: Gen Xers will have higher cancer rates than boomers, study forecasts

One reason for this is that HGOC doesn’t have specific symptoms in the early stages of the disease. Also, during this time, tumors are very small and conventional biomarkers — such as the CA-125 blood test, which detects raised levels of a cancer-related protein — are not sensitive enough to detect them.

However, the findings of a new study, published June 14 in the journal Cell Reports Medicine, may help doctors diagnose ovarian cancer much sooner, allowing for earlier treatment before the cancer has spread and, potentially, longer survival.

In the study, researchers discovered a blood-based immune biomarker that they say could be used to detect HGOC up to four years before most cases are currently diagnosed.

They uncovered this biomarker after analyzing blood samples taken from 466 patients who, within five years of their sample being drawn, went on to be diagnosed with ovarian cancer using conventional clinical tests.

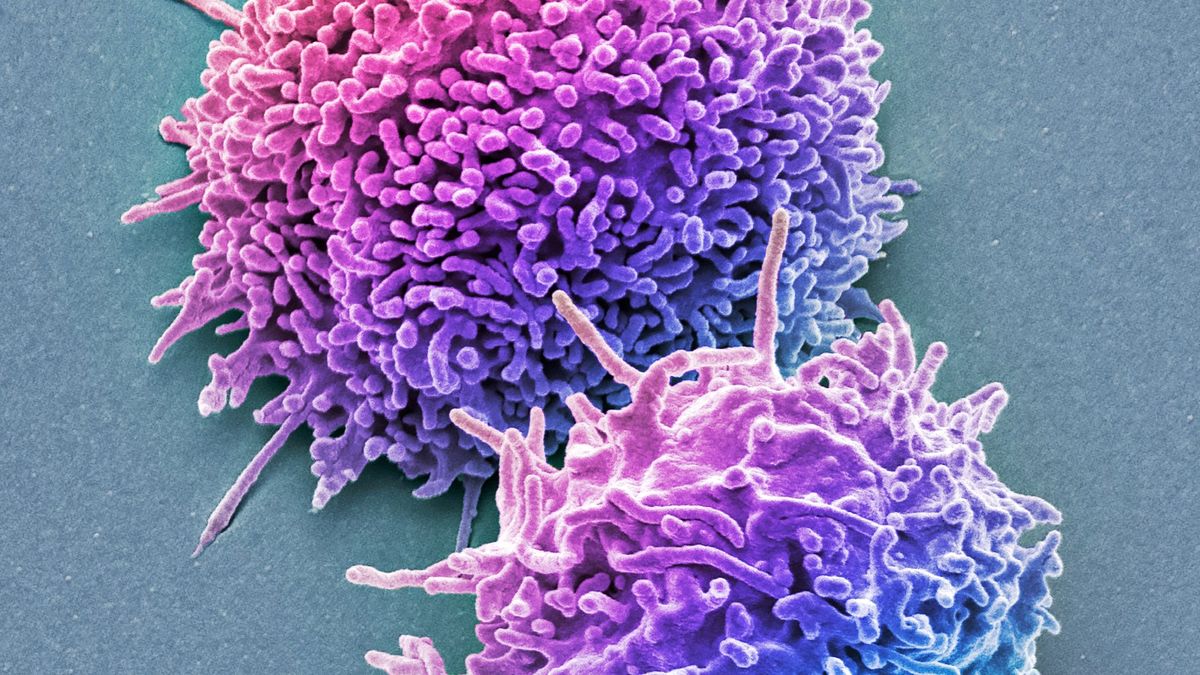

Specifically, the team noticed strong differences in the numbers of immune cells called T cells in their blood that were primed to recognize and attack cancer cells, compared with those found within the blood of a comparison group of women who did not go on to develop cancer.

These signals could be detected two to four years before diagnosis and show that the immune system is actively fighting the disease, the study authors said.

The research is still in its early stages. However, this “unprecedented discovery” could one day inform the development of new tests that detect this newly identified biomarker, the team said.

“Early detection of ovarian cancer could mean the difference between life and death for millions of women,” Bo Li, co-senior study author and a researcher at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Center for Computational and Genomic Medicine, said in a statement.

“We believe our findings can be a gamechanger, providing insights for the development of an immune-based biomarker to detect early-stage ovarian cancers.”

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line “Health Desk Q,” and you may see your question answered on the website!

%20(2)%20(1).jpg)

Discussion about this post