Promises to improve the UK’s food security feature in the election manifestos that have been published ahead of the vote on 4 July.

The Conservatives say they can provide a future where “national, border, energy and food security are put first”. Labour says that “food security is national security”.

Food supplies have been impacted by geopolitical conflicts, extreme weather events and rising costs around the world in recent months.

The UK government recently described its food security situation as “broadly stable”, but that it is facing “longer-term risks” from climate change.

Food security is “very low on the political agenda”, a food policy expert tells Carbon Brief, adding that “politicians really don’t yet get how important and how fragile the food system is”.

Below, Carbon Brief examines the range of factors tying into the UK’s food security, how they are impacted by climate change and how some of the biggest parties discuss these issues.

How food secure is the UK?

In a broad sense, food security refers to people in a particular country or region having enough access to food.

This is achieved when “all people, at all times” have access to enough “safe and nutritious food” to meet their needs and preferences for an “active and healthy life”, according to a definition agreed at a 1996 World Food Summit.

Sufficient “access” to food depends on a number of different factors, including costs, supply, types of food, nutritional needs and where the food comes from. These factors vary on a national and local level.

Food security in the UK is “broadly stable”, according to the government’s first food security index released last month. However, this follows a “challenging period of global supply chain shocks”.

The government says that this stability should also be taken in the context of “longer-term risk from climate change”. (See: How does climate change impact food security?)

In terms of food supply, it says that the ratio of food produced in the UK to food imported from other countries was “broadly stable” in 2022, which is the most recent data available.

The UK produced 60% of its own food and 73% of “indigenous foods” that are natively grown, such as carrots and onions. This was a drop of 1% in each case compared to 2021.

Overall, the UK imports around 40% of its food, the government notes. As the chart below shows, these imports come from a range of countries, including the Netherlands, France and Ireland.

The UK produces most of the cereals, meat, dairy and eggs eaten by people across the country. It is much more reliant on imported fruit and vegetables than any other type of food, which is a similar situation to Ireland.

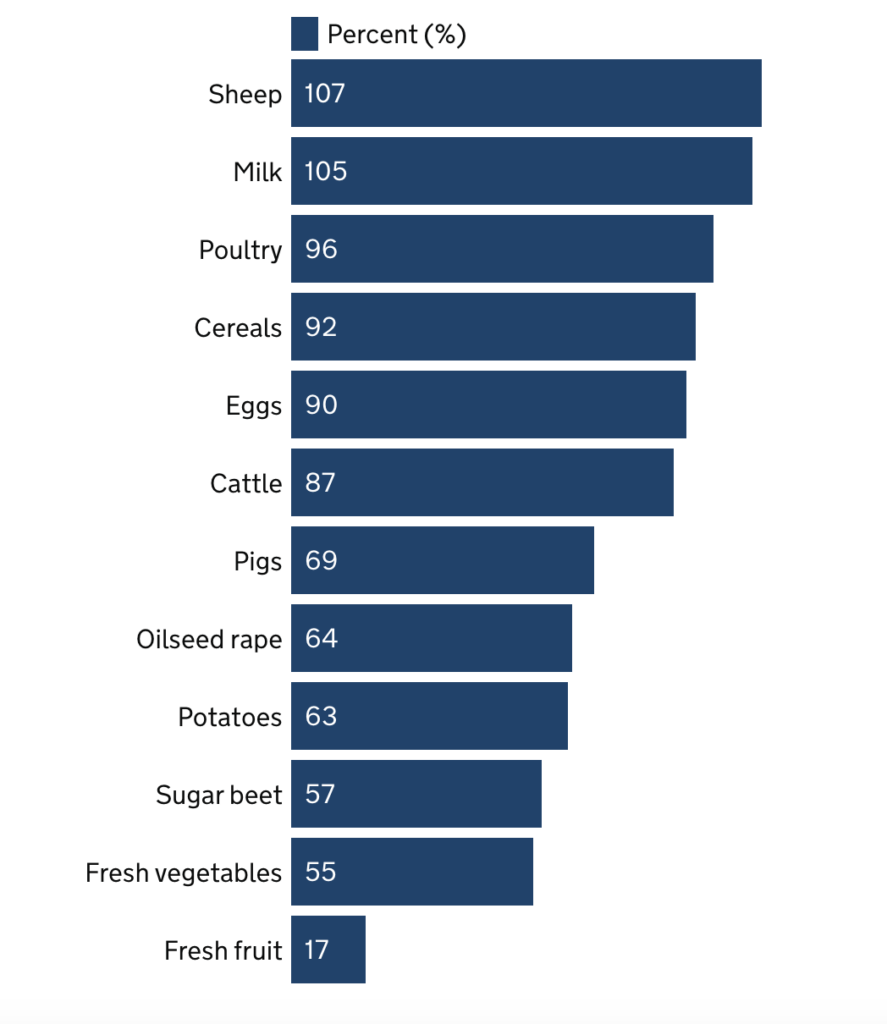

The chart below outlines the “production to supply ratio” of raw foods. The figures indicate, as a percentage, how much of each of the consumed food types are produced in the UK. So, for example, the UK produces 17% of the fruit and 55% of the vegetables it consumes. In contrast, the UK produces more lamb and milk than it consumes.

Different foods are imported from different countries around the world, such as citrus fruits from Spain, tomatoes from the Netherlands and India, and rice from Pakistan.

Supplies can, therefore, be hit by extreme weather abroad. This has happened numerous times, including when cold weather in Spain and Morocco led to severe shortages of lettuce, tomatoes and other crops in the spring of 2023.

In terms of production, the balance between home-grown and imported food is “integral to UK food security” as the country’s climate is unsuitable for products such as rice, bananas and tea, the government index says.

It adds that the government is “not complacent” about food security risks, especially from global “volatility”, climate change and biodiversity loss – all of which have “intensified” in recent years, it notes.

Another key aspect of food security is affordability. Food prices have risen substantially around the world in recent years.

Carbon Brief recently spoke to a range of scientists and policy experts about the reasons for this, which include geopolitical conflicts, extreme weather events, high input costs and increased demand.

In the UK, the overall cost of food and non-alcoholic drinks increased by 25% between January 2022 to January 2024, according to the Office of National Statistics.

Around half of the respondents to a Food Standards Agency survey of the general public said they are “highly concerned” about the affordability of food. This figure doubled over the course of three years – from 26% in 2020 to 51% in 2023.

The percentage of survey respondents classified as “food insecure” stood at 25% by January 2023. Food insecurity means having limited or uncertain access to adequate amounts of food, the FSA says.

These results show that “the majority of people are worried about food prices”, the FSA chief Emily Miles said in a statement.

Prof Tim Lang, an emeritus professor of food policy at City University of London, says that food security is “very low on the political agenda” in the UK. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Politicians really don’t yet get how important and how fragile the food system is and its reliance on not just fossil fuels, but over half a century of investment into a particular model of efficiency which has all been about cutting options, cutting slackness, or perceived slackness, in the food system.”

Back to top

What have UK political parties pledged on food security?

In an interactive manifesto tracker, Carbon Brief recently examined the pledges made by the UK’s main political parties ahead of the election.

Both the Conservative government and the Labour opposition have been criticised by farming and food industry groups for not going far enough in their plans on food and agriculture.

The Conservatives say they can provide a future where “national, border, energy and food security are put first”. They pledge to introduce a legally binding target to enhance the UK’s food security.

They also pledge to deliver the goal for at least half of the money spent on food in schools, hospitals and other public sector services to be used for food produced locally or to “higher environmental production standards”.

This proposal from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs defined “locally produced” as food that is grown or made in the same region, or a neighbouring county, as it is consumed.

These “higher” standards of production include organic farms or farmlands showing integrated management of natural habitats and biodiversity, soil management, pollution control and nature conservation.

Queries from Carbon Brief to the Conservative press office asking for more detail on their food security policies were left unanswered.

Labour’s manifesto says that “food security is national security” and that the party will “champion British farming whilst protecting the environment”.

Similar to the Conservative goal, the party will set a target to produce half of food purchased in the public sector either locally or in a way that is “certified to higher environmental standards”.

Carbon Brief’s request for more detail on this policy from the Labour press office also went unanswered.

A letter from the National Farmers’ Union (NFU), the British Retail Consortium and other groups to the leaders of the Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat parties criticised the lack of focus on food security in their manifestos, the Guardian reported last week.

The letter said the groups “heard very little about food security” compared to defence and energy security in recent weeks, the newspaper said. It added:

“The lack of focus on food in the political narrative during the campaigns demonstrates a worrying blind spot for those that would govern us.”

The Conservative manifesto pledges to increase the UK’s farming budget by £1bn over the term of the next parliament.

Labour committed to maintaining England’s post-Brexit funding programme, the Environmental Land Management Schemes (read Carbon Brief’s Q&A here), but did not explicitly mention the UK’s agricultural budget.

NFU president Tom Bradshaw described this as “concerning”, the Daily Express reported. He told the outlet:

“Looking at the profitability of the farming sector, it’s on a knife edge.”

The Scottish National Party does not directly mention food security in its manifesto. It discusses agricultural funding, saying that the devolved Scottish government has received “no commitment from Westminster on any future funding for farming after 2025”.

The SNP calls for the UK government to increase farm funding and provide “certainty through multi-annual funding frameworks”.

The Liberal Democrats has pledged to introduce a “holistic and comprehensive national food strategy to ensure food security” alongside tackling food prices, ending food poverty and improving health and nutrition.

The party also promises to put an extra £1bn per year towards England’s Environmental Land Management Schemes.

Gareth Redmond-King, the international lead at the Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit thinktank, says that these funds help farmers tackle the “already biting” impacts of climate change. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Green farming supports help UK farmers invest in their soils, plant hedgerows and create new wetlands that will aid resilience to floods and drought, protecting yields.”

Back to top

How does climate change impact food security?

Extreme weather can harm food supply and production, therefore impacting food security.

Heatwaves destroy crops and endanger agricultural workers. Heavy rainfall floods fields. Drought reduces crop yields. Climate change is a key driver in the increasing frequency and severity of these extremes.

Redmond-King says that “worsening climate impacts are a huge and growing threat to food security” around the world. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The only solution we have to avoid that getting progressively worse is net-zero emissions to limit temperature rises.”

Farmers in the UK have recently been affected by “soggy and turbulent weather”, Bloomberg reported.

The UK had its eighth-wettest winter on record last year and a wetter-than-normal spring. Carbon Brief analysis shows that UK winters have become 1C warmer and 15% wetter in the past century.

Earlier this year, the Guardian reported that there could be food shortages and price rises due to this extreme weather.

This could lead to more shipments from abroad, but the newspaper said that “similarly wet conditions in European countries such as France and Germany, as well as drought in Morocco, could mean there is less food to import”.

In 2022, the heatwave which saw UK temperatures hit 40C for the first time pushed farmers “closer to the brink”, the Daily Telegraph reported at the time.

The hot, dry weather in July left farmers “watering crops which wouldn’t normally need watering such as sugar beet and maize”, the newspaper said, while “industry chiefs warned that very hot and sunny days were starting to stress apple trees and scorch fruit”.

It added that “fears that high temperatures will damage this year’s harvest in Britain, Europe and North America sent crop prices 7% higher last week, the biggest jump since the early days of the conflict in Ukraine”.

A rapid attribution analysis suggested that human-caused climate change had made the UK’s record-breaking heatwave at least 10 times more likely. A separate study found that climate change had made the droughts across the northern hemisphere in 2022 at least 20 times more likely.

Speaking to Carbon Brief for a recent article, Prof Andy Challinor, a professor of climate impacts at the University of Leeds, said that “climate change is beginning to outpace us because it is interacting with our complex interrelated economic and food systems”.

He added that the way food systems have been set up “has huge implications for stability and resilience – or lack thereof”.

Lang tells Carbon Brief that there is some “lip service [and] some good initiatives” to address risks from climate change and biodiversity loss, but he adds:

“There are great things going on, but they are small compared to the enormous change that needs to happen.”

Back to top

How can the UK food system better prepare for shocks?

Lang says the next UK government has a “horrendous task” in tackling issues such as extreme weather, global shocks and other impacts negatively affecting food production.

He has been working on a report about UK food security and preparing for food shocks for the National Preparedness Commission, an independent body that promotes policies to prepare the UK for shocks. This is due to be released by the end of this summer.

Lang believes that a system change is necessary to deal with the range of different shocks and to tackle the food system’s contribution to climate change.

The global food system is responsible for around one-third of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. Within this, as much as half of those emissions come from rotted or otherwise wasted food, a 2023 study found.

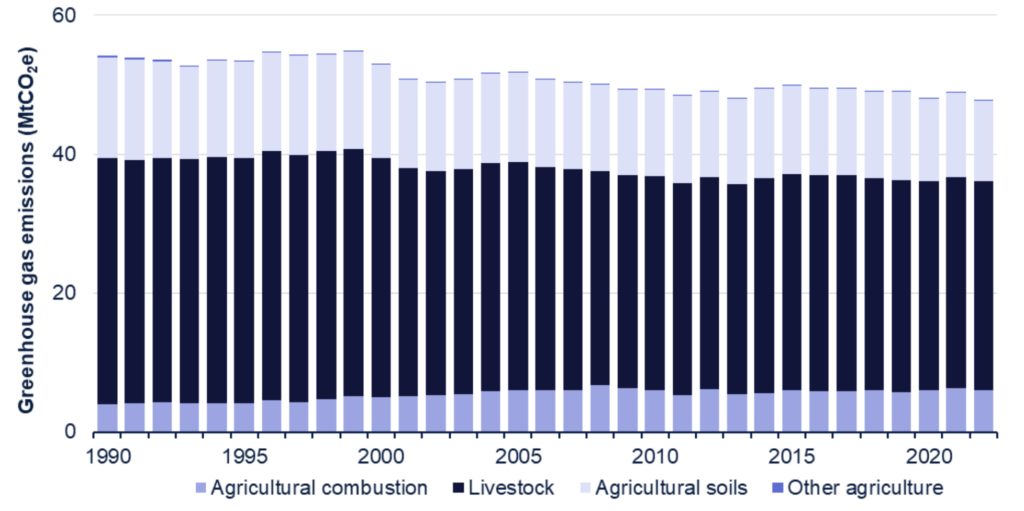

In the UK, 12% of all greenhouse gas emissions come from agriculture. Livestock is by far the biggest contributor to these emissions, as shown in the chart below.

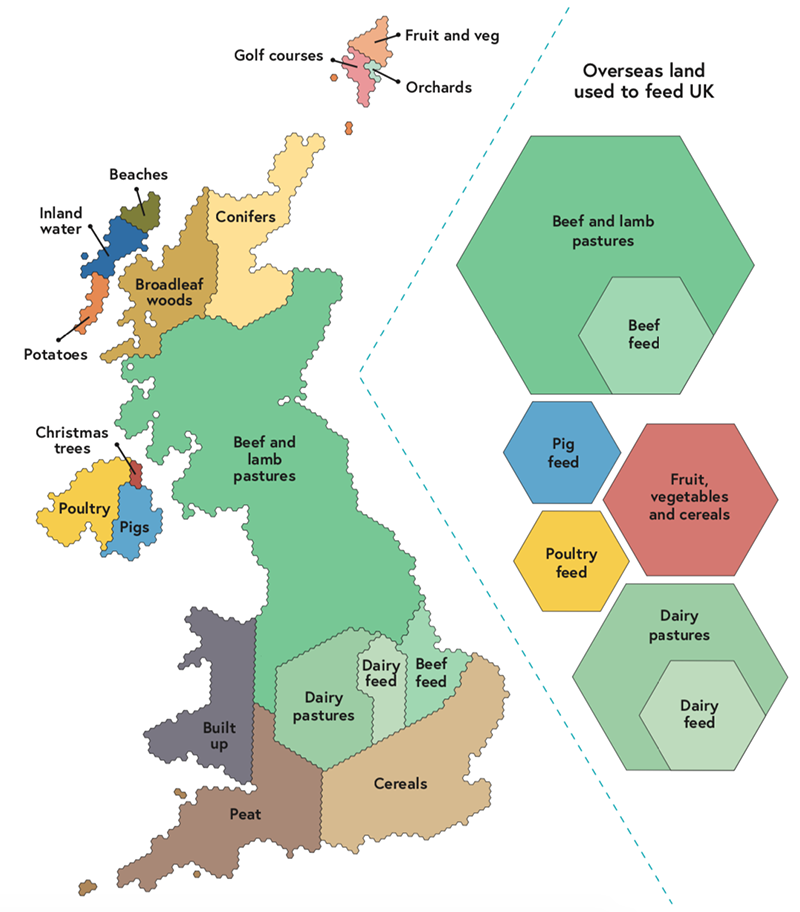

Around 70% of the UK’s land is used for agriculture. Globally, half of all liveable land is used for agriculture.

England’s National Food Strategy, published a few years ago, called for a rural land-use strategy to figure out the best ways to use land for nature, carbon sequestration, agriculture and other purposes.

The UK is due to release its delayed land-use report for England later this year. Before the general election was called, a conservative peer said the report would be published before the parliament’s summer recess.

A spokesperson for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs declined to comment on the current status of this report as it is an issue for the next government.

Food security should be a “central tenet” of this framework, the UK parliament’s Environmental Audit Committee said in December 2023.

The chart below highlights how land is currently allocated in the UK (left) and how much overseas land is used to produce food for the UK (right).

On next steps, Lang says that he would like to see a number of actions from the next government on food security. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We need a national council of food policy. We need to have high priority to agri-food reform. We have got to actually start a programme of educating and teaching people better how to do things. We have got to get a grip on the runaway food manufacturing industry.

“At the moment, the politics of food is just blame. And blame doesn’t get political change.”

Back to top

Sharelines from this story

Discussion about this post