Extreme heat hit home in June, with little rainfall throughout the month. That combination brought the rapid onset of drought conditions in North Carolina.

Summer Sizzle Shows Up

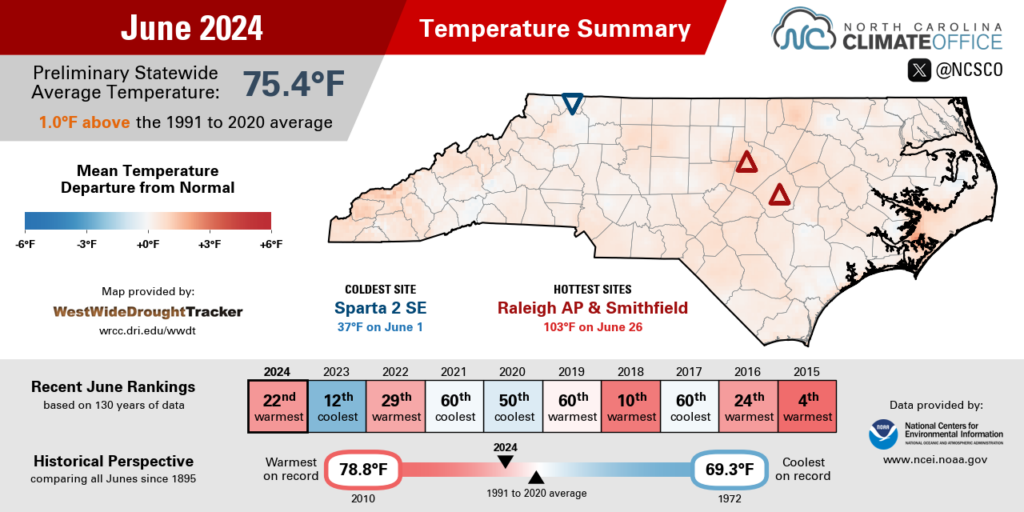

A boost from a late-month heat wave helped put our June temperatures well above normal. The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) reports a preliminary statewide average temperature of 75.4°F. That ranks as our 22nd-warmest June out of the past 130 years and the warmest since 2018.

For much of eastern North Carolina, it was one of the top five warmest Junes on record, including the 3rd-warmest in Rocky Mount, tied for the 3rd-warmest in Raleigh, tied for the 4th-warmest in Hatteras, and the 5th-warmest in Lumberton.

Early in the month, offshore high pressure helped keep our temperatures a few degrees above normal, but short of the extremes that would come later as Mother Nature kept throwing blankets on top of our already sun-soaked state.

By June 22, our temperatures climbed into the mid to upper 90s as surface high pressure moved overhead and an upper-level high pressure system began building over the Southeast US. As that pattern intensified, our temperatures continued to climb during the following week.

On June 23, Raleigh hit 100°F to tie its daily record high. It was the first hundred-degree reading there this year, but only the first of four days that warm in June: the most in a single month there since July 2012.

On June 26, a warm front pushing in from the southeast moved the mercury even higher, hitting triple digits in parts of the Sandhills and eastern Piedmont.

Lillington got to 100°F, marking the earliest occurrence of temperatures that hot since June 17, 2015. Our ECONet stations in Hamlet and at the Clayton DAQ Profiler each reached 101°F. And both Raleigh and Smithfield topped out at 103°F, the first day that warm since 2012 at the RDU Airport station.

By June 29, a broad dome of upper-level high pressure blanketed the Carolinas, giving another afternoon of extreme heat including a high of 91°F at our usually maritime-moderated station on Bald Head Island. That was its warmest day since August 21 of last year.

It wasn’t just the afternoons when we felt the heat last month. Our nights were also warm and steamy. On June 23, Fayetteville, Greensboro, and Raleigh all tied or broke their daily record high minimum temperatures, while on June 26, Raleigh broke both its daily high and low temperature records.

Through the full month, it was hard to get a break from the heat. In Lumberton, 26 of 30 days had temperatures of 90°F or greater: its 2nd-most 90-degree days on record in June. In Greenville, 21 days hit the 90-degree mark last month, which was its 4th-most in any June and the most since the record of 23 days in 2010.

Dry Days Dominate

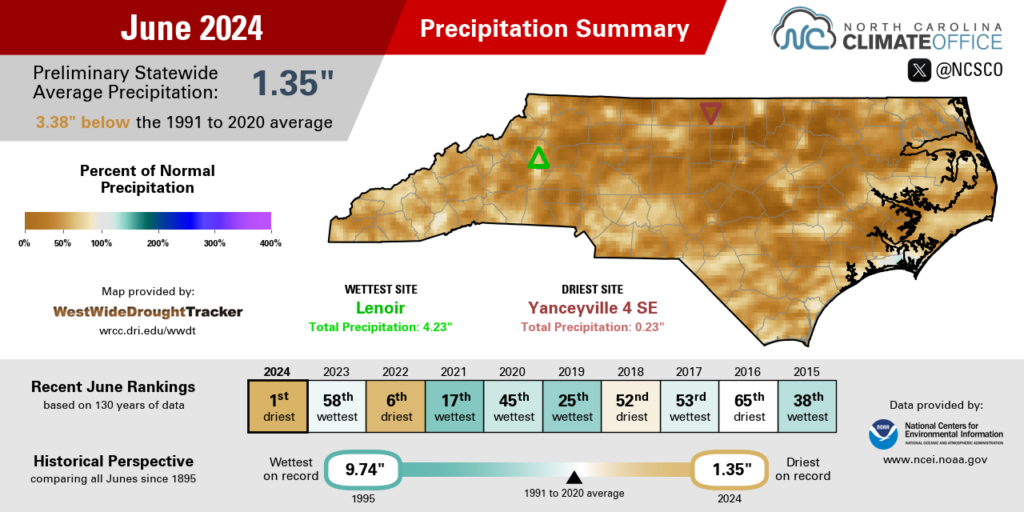

Amid our hot weather pattern, rain was rarer than we’ve ever seen throughout the month in North Carolina. NCEI notes a preliminary statewide average precipitation of 1.35 inches, making this our driest June on record dating back 1895.

A number of local sites also set new records for a lack of rainfall. It was the driest June on record in Plymouth (0.24”), Tarboro (0.58”), Clinton (0.71”), and New Bern (0.89”) based on data going back at least 50 years at all stations.

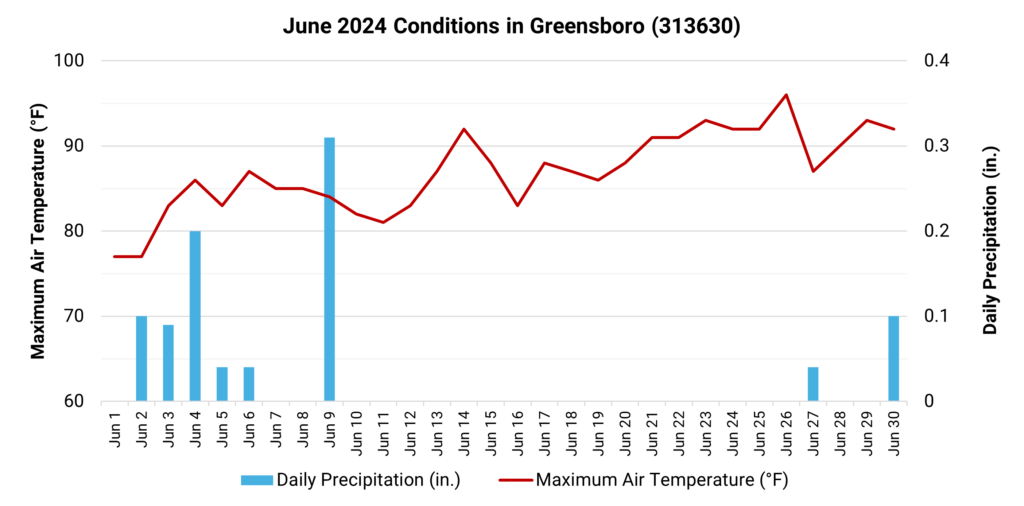

Parts of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain measured less than an inch of rain all month, including only 0.92 inches in Greensboro and 0.75 inches in Henderson in the 4th-driest June on record at both sites, and 0.90 inches in Lumberton in its 2nd-driest June.

Most western sites fared slightly better in terms of total rainfall, but it was still a dry month in the Mountains. Franklin also notched its driest June on record with just 0.97 inches in total, while with 1.48 inches, Boone had its 3rd-driest June since 1980.

As a carryover from our wet May, this June started with some sizable rainfall totals in a few areas. On June 4, a small shower in the Triangle dropped an impressive 1.85 inches at the RDU Airport in a single hour. Farther west, Lenoir had 3.03 inches over a two-day period on June 4 and 5.

A cold front moving in from the northwest brought more modest totals of half an inch or less on June 9, but in most areas, that would be the last rain they’d see for almost two weeks.

With high pressure in place, the atmospheric spigot turned off mid-month, giving a lengthy string of dry days. Hickory, Greensboro, and Laurel Springs each had 17 consecutive days with no measurable rainfall between June 10 and June 26.

Fayetteville went 19 days with no rainfall through June 29. That was its longest dry stretch since a 23-day streak in the fall of 2016, which at that time was a welcome relief from the rain and flooding from Hurricane Matthew. And in Greenville, the month ended with 23 consecutive rain-free days: the longest such streak there since October and November of 2000.

A series of weak cold fronts sagging southward in the final week of June did bring a bit of rain to wrap up the month. On June 24, showers along the coastline dropped up to 2.74 inches in Newport, while June 30 saw more than 2 inches fall in pockets of eastern North Carolina, including river-raising totals of up to 8 inches in parts of Sampson County.

The late-month return of rainfall was a silver lining to the very dry June, but in most areas, it was just a drop in the bucket compared to what we missed out on earlier, which helped drought rapidly expand across the state.

Drought Develops and Deepens

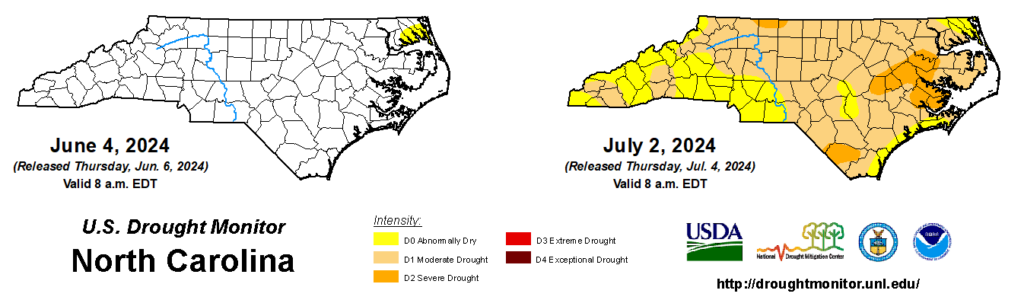

Because of how dry our June was, it’s easy to forget just how wet we were one month earlier. May featured multiple heavy rain events and more than 10 inches of total precipitation in parts of the Piedmont, which left us with a nearly clear drought map and solid soil moisture levels heading into the summer.

The combination of extreme early-season heat and persistent dryness through most of June quickly burned through that excess moisture from May, and as of this week, Abnormally Dry (D0) or drought conditions cover 99.98% of the state.

With a degradation of two to three categories on the US Drought Monitor within a four-week span, we’ve easily met the criteria for flash drought, and we got there in nearly record-breaking fashion.

From June 11 to 18, we had the state’s second-largest weekly expansion of Abnormally Dry (D0) conditions since the US Drought Monitor officially launched in 2000. That put an additional 60.88% of the state into the lowest-level USDM category. The only greater weekly expansion of D0 was a 72.22% change in March 2007 at the outset of that multi-year drought.

The following week, the June 25 map saw 56.54% of the state enter Moderate Drought (D1). That was also the second-biggest week-to-week increase in D1 coverage, behind only the 57.10% change on October 30, 2001.

The latest map from July 2 has 9% of the state in Severe Drought (D2), and almost 75% of the state in either Moderate or Severe Drought. That’s a remarkably rapid degradation over the course of less than one month.

Along with being perhaps the fastest-emerging summertime drought in recent memory, it’s happening early in the season. Other notable summer flash droughts started in July 2010, July 2015, and August 2023 – all the result of a steadier onslaught of hot, dry weather throughout the summer.

In a single month with those sorts of conditions, we already saw wide-reaching impacts this June:

- As soil moisture evaporated, lawns turned yellow or brown, gardens got thirsty, and trees began dropping leaves in order to conserve moisture.

- Farmers watched their crop conditions decline at perhaps the most sensitive point in the growing season to precipitation. In particular, a lack of rainfall during corn’s silking phase can reduce yields by 3 to 4% per day, while soybeans may stop flowering, which means seed pods may not fill. Crop progress and condition reports from USDA/NASS showed these effects in June. Just 3% of corn was rated in poor condition to begin the month, compared to 68% in poor or very poor condition as of June 30.

- Streamflows were at or above normal in May, but finished June below normal across much of northern and eastern North Carolina. The greatest decreases were in the northern Piedmont. For instance, Hyco Creek near Leasburg saw discharge levels decline from 11.9 cubic feet per second on May 31 to just 0.14 cubic feet per second on June 30.

- Reservoirs have barely been hanging onto their target levels, and most have been making minimal downstream releases just to stay there. For the month of June, net inflows into Falls Lake were negative due to high evaporation rates, little rainfall in the headwaters, reduced flows upstream, and sharing that limited moisture with the City of Durham’s own rain-starved reservoirs.

- Some local water systems, particularly in eastern North Carolina where large reservoirs are not available, implemented water usage restrictions. Johnston and Pamlico County utilities have requested voluntary conservation, and the West Carteret Water Corporation asked customers to limit outdoor use to make sure the water supply and water quality from the Castle Hayne Aquifer can last.

- Although wildfire activity tends to decrease once green-up is completed in the spring, fires can still occur during the summer, particularly as live and dead vegetation dries out. Last month, the North Carolina Forest Service reports 490 wildfire incidents burning 1,541 acres on state and private lands – both around double the normal June figures. The largest fire of the month burned 545 acres in Carteret County.

The introduction of Severe Drought (D2) in parts of the state this week represents a step-up in drought impacts. D2 is often associated with more deeply entrenched dryness in the ground, an unavoidable loss of some crop yields, and the introduction of conservation measures, as we’ve already seen in some eastern areas.

Reaching the D2 level just two weeks after the initial expansion of Abnormally Dry conditions makes the current drought all the more impressive, and it leaves us hoping that July will be more like our moist May than our juiceless June.

.png)

Discussion about this post