What do you do when a dead whale washes up on the beach – bringing up to 40 tonnes of foul smelling, glutinous mess attracting scavengers and covered in flies?

You could transport it to a rendering facility for by-products, compost or bury it, let it decompose naturally in place, or even sink the remains and use explosives to break it down.

In Australia, the most common solution is to cart whale remains off to landfill.

These methods can be costly, and technically difficult and can pose public health risks. But a new study shows there’s another, more ecosystem-beneficial option – towing whale remains out to deeper water.

This allows its nutrients to stay in the marine ecosystem following decomposition.

The method has been used in Australia and internationally before, but it is not always successful. Dynamic interaction between wind, waves, and current forces influences how the remains drift, and can result in them moving back to shore or into shipping lanes.

“As we’ve seen more and more whales stranding on Australian beaches in past years, the effective, safe and culturally sensitive removal of whale remains near or on public beaches has become a major issue,” says Olaf Meynecke of Griffith University’s Whales and Climate Research Program.

“Our study shows that forecasting of where whale remains might end up when floating at sea is possible with surprisingly high accuracy.”

Meynecke led the case study involving a 14-metre female humpback whale, which was found floating deceased, likely to due to ship strike, in coastal waters off Queensland’s Noosa Heads in July 2023.

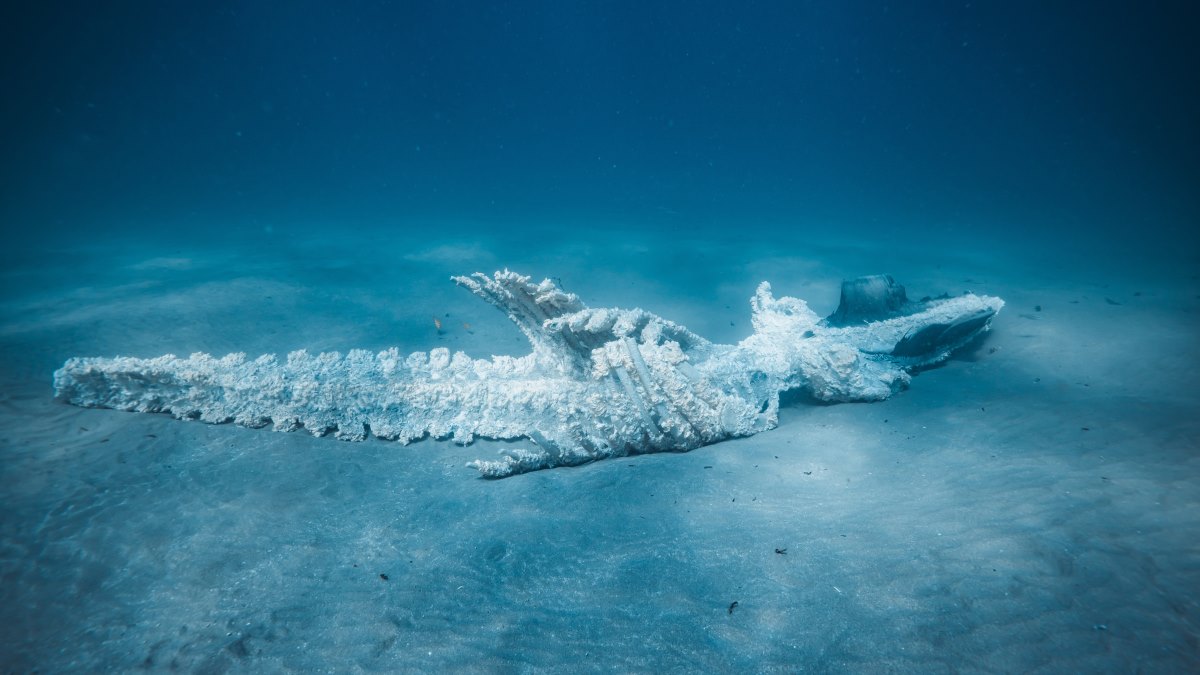

The researcher intercepted the remains before they could wash onto land and redeposited them 30 kilometres offshore. A satellite tag fitted to the whale carcass allowed them to then track its position as it drifted with the wind and currents for 6 days before sinking to the seafloor.

“Perished whales provide a substantial nutrient source for marine ecosystems, and strategically placing whale remains offshore can enhance nutrient cycling and foster biodiversity, contribute to carbon removal and marine floor enrichment for up to 7 years,” says Meynecke.

“Their gradual decomposition sustains scavengers and detritivores and support microbial communities and deep-sea organisms.”

These findings provide an initial forecasting tool to predict where whale remains could drift when deciding whether offshore disposal is the best approach for removing them.

“The best strategy for handling whale remains depends on multiple factors and should be decided on a case-by-case basis. Offshore disposal can be an ethical, cost-effective, and safe option if managed appropriately,” says Meynecke.

“By integrating scientific research and practical management strategies presented in our study, we can enhance our ability to predict and effectively manage the drift of whale remains, ensuring that ecological benefits are maximised while minimising adverse impacts.”

Do you care about the oceans? Are you interested in scientific developments that affect them? Then our email newsletter Ultramarine is for you. Click here to become a subscriber.

Discussion about this post