Boiling Macaroni in Space? You’ll Need a Weirdly Shaped Pot

Astronauts still survive on freeze-dried meals. Could better food, aided by cooking gadgets designed to be used in microgravity, help them to thrive?

On Earth, hot bubbles rise and gravity keeps water at the bottom of a pot. There’s no such luxury in space.

Jennifer A Smith/Getty Images

Food scientist Larissa Zhou was getting into rock climbing and backpacking near Seattle when she realized that her day job and hobbies were converging. Her dehydrated backcountry meals tasted increasingly bland to her, and they lacked appetizing texture—she began feeling sorry for the International Space Station (ISS) astronauts who sustain themselves on similar stuff for months at a time. “I don’t want people to eat freeze-dried food in space forever,” says Zhou, who recently received a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering and materials science from Harvard University. “I actually want people to cook.”

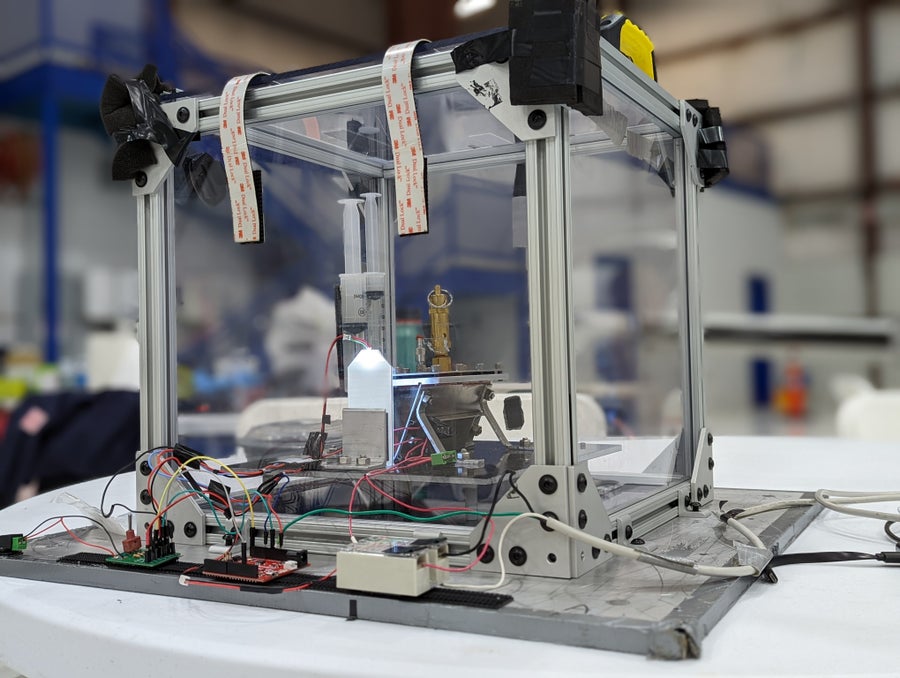

Zhou has spent the past four years working on a machine to boil food in microgravity. She named it H0TP0T, evoking the traditional Chinese custom of eating from a communal boiling pot (the zeros in the name refer to its intended home in microgravity). The aluminum-and-glass device she designed belongs to a recent wave of experimental technologies that aim to improve the eating experience for space travelers. In 2019 astronauts baked cookies on the ISS using a small oven. Researchers have also developed sauté stations and deep fryers, among other kitchen gadgets, adapted for microgravity. But such devices have yet to make it into long-term orbit.

Because basic astronaut safety and mission success are always the top priorities, some researchers dismiss culinary comforts in space as superficial. But Zhou and a contingent of other food scientists insist their work is essential to astronauts’ physical and mental health, especially on longer missions. Ariel Ekblaw, founder of the M.I.T. Space Exploration Initiative and CEO of the Aurelia Institute, which researches future space habitats, says it’s time “to think about a life in space that is as much about thriving in space as it is about surviving.” To demonstrate this vision of more comfortable space life, the Aurelia Institute is building a mock space habitat called the TESSERAE pavilion, set to open in early August in Boston and later to exhibit in Seattle. In planning the project, Ekblaw and a colleague interviewed nearly two dozen astronauts—who often mentioned better cooking options and tastier food as important ways to improve their well-being. Reflecting that, a H0TP0T (suspended upside down to indicate astronauts can use the device in any orientation) will hang in the experimental habitat’s kitchen.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Zhou chose to work on a microgravity water cooker because grains—an excellent and shelf-stable source of both proteins and carbohydrates—usually require boiling. But boiling food in space is a particularly thorny challenge. On Earth, gravity keeps water at the bottom of a pot. In microgravity, however, keeping water contained within the pot so it doesn’t float away is a big issue. But water molecules are also attracted to each other, and to any surface they touch; when water is weightless, capillary action and surface tension can have a much larger influence on keeping water in one area within the pot.

H0TP0T’s wedge shape exploits these forces to trap water in the boiler’s narrowest corner. The design was born out of a conversation Zhou had with a friend who works in satellite propulsion and faced a similar problem: how to keep fuel contained in space so it can predictably reach an engine and ignite. The resulting wedge-shaped “pot,” which looks like a tall slice of cake tipped onto its point, consists of a sheet of aluminum alloy bent at a 45-degree angle. A pizza slice–shaped pane of Pyrex glass covers each end.

The prototype H0TP0T device, a small triangular object, sits within a transparent box.

Another problem concerns the science of boiling itself. On Earth, buoyancy-driven convection, in which cooler and denser water falls below hotter liquid, relies on gravity to distribute heat evenly and remove bubbles from the surface. In space, that doesn’t happen. Boiling water instead forms larger bubbles that loll around in place; this could lead to poorly cooked food. Thus, food has never been cooked by boiling in space. On the H0TP0T, however, heating elements are screwed to the outside of the aluminum shell to heat a large surface area of the pot, which lessens the need for gravity-driven convection to heat the water evenly. The container’s metal lid also has a pressure valve to release steam.

In late May 2022 a miniature prototype H0TP0T filled with water—and three pieces of uncooked rigatoni pasta—was bolted to the floor of a modified Boeing 727-200, an aircraft operated by the Zero Gravity Corporation that simulates weightlessness by making repeated sharp dives. As Zhou watched the heated container during 20 of these parabolic free falls, some water did creep into the wedge’s far corners. But most stayed in its narrowest section. The wedge shape also allowed for the separation of the liquid water and bubbles of gaseous steam so the noodles could cook evenly. By the end of the 45-minute flight, the pasta was well past al dente. A year later, Zhou and the cookware took another one of these flights. This time she tested the experience future astronauts might have when actually using H0TP0T, “unscrewing a gazillion things” to extract the pasta—and finally eating a piece of rigatoni that had been cooked in the machine, though the morsel was uncooperative at first. “It was like a cat-and-mouse game between my mouth and the piece of pasta,” Zhou says.

Ralph Fritsche, former senior project manager for space crop production at NASA and a current contractor at the space agency, says it’s important to consider how stand-alone technologies such as H0TP0T would work within the whole food system—from growing to harvesting and processing the ingredients, all in space. So far NASA has experimented with how to grow plants in space, but not with processing or cooking them. “Everything we’re doing in the near term is going to be pick and eat stuff; we’re not going to have the hardware to process and prepare it,” Fritsche says. He also notes that equipment for testing new technologies has to compete for limited payload space on the ISS, so machines can simmer in the development stages for years or even decades.

But Zhou still wants to continue developing H0TP0T. She’s aiming to try to adapt it along the lines of a sous vide system, in which bags of portioned water and grains are submerged in hot water to cook. This way the pot stays cleaner, and the boiling water can be reused. Zhou is also looking for ways her technology could be useful on Earth. She says she once thought a H0TP0T-sous vide combo might provide people with a way to cook food during disasters, but she insists on being careful not to force a humanitarian application that isn’t truly beneficial. “The dream would be to develop a technology for space in parallel with developing it for Earth-based applications,” Zhou says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d1/82/d18228f6-d319-4525-bb18-78b829f0791f/mammalevolution_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post