Wildfires have exploded across Canada, sending thick plumes of smoke across a vast territory.

At least 525 lightning-sparked wildfires are burning in heat- and drought-plagued British Columbia, Alberta and the Northwest Territories — including this one, imaged by the Sentinel-2 satellite on July 17, 2024:

A wildfire burns in Canada’s Northwest Territories, as seen in this image acquired by the Sentinel-2 satellite on July 17, 2024. (Credit: Modified Copernicus Sentinel data processed by Tom Yulsman)

This blaze appears to be throwing off a giant fire cloud known as a pyrocumulonimbus, or pyroCb. These clouds punch high into the atmosphere, sometimes even into the stratosphere — a phenomenon I’ll explain in greater detail in my next column.

As of the morning of Friday, July 19, the smoke from Canadian wildfires stretched 2,500 miles from west to east, and covered about 1.5 million square miles — equivalent to about half the area of the contiguous United States. The blazes are a reminder of last summer’s horrific wildfire season, Canada’s worst on record by far.

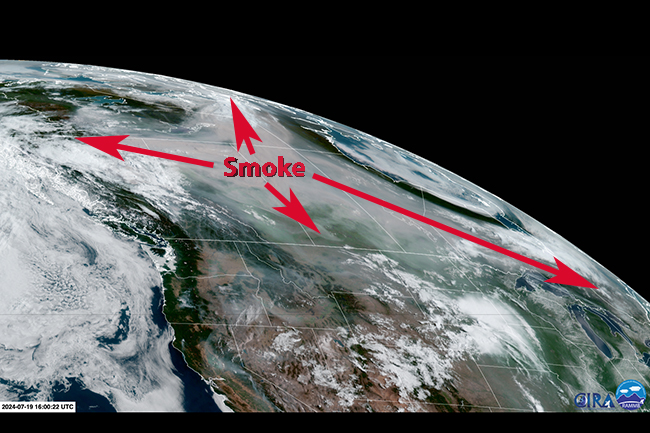

This animation of GOES-18 satellite images, acquired yesterday, shows the smoke billowing out from multiple wildfires:

Smoke billows from multiple fires that have erupted in drought-plagued western Canada, as seen by the GOES-18 satellite on July 18, 2024. (Credit: SLIDER RAMMB/CIRA)

The smoke will continue to spread in coming days. Here’s the smoke forest for Saturday, July 20:

Smoke from hundreds of wildfires is forecast to blanket large portions of Canada and the United States by Saturday, July 20, 2024. (Credit: NOAA)

In the United States, more than 60 large, uncontained wildfires are burning. Counting all blazes, including large and small, and both contained and uncontained, there are at least 105 incidents being fought by more than 19,000 personnel, according to the most recent Incident Management Situation Report from InciWeb, a U.S. government interagency incident information management system.

Climate Change Connections

Over the past two decades, rising temperatures, longer droughts, and a thirstier atmosphere — all arising from human-caused climate change — have played a major role in increasing the risk and extent of wildfires in the Western United States.

Multiple strands of research have documented the connection between climate change and wildfires. For example, a 2016 study linked climate change to a doubling in the number of large fires between 1984 and 2015 in the western United States. More recently, a 2021 study found that climate change has been the main driver of an increase in fire weather in the region.

In that year, the North American wildfire season saw record breaking fire-weather and a large number of intense blazes that exhibited extreme behavior. In July of 2021 alone, wildfires scorched 12,355 square miles of Canada and the United States — an area more than two and a half times the size of the New York metropolitan area.

These record-setting wildfires “were catalyzed by an intense heat dome that formed in late June over western North America,” according to a study published in the journal Nature. The event lasted 59 percent longer than it would have without a warming climate. It was also 34 percent larger and 6 percent more intense.

“Climate change will continue to magnify heat dome events, increase fire danger, and enable extreme synchronous wildfire in forested areas of North America,” the researchers concluded.

Blazes Burn the Siberian Arctic

Of course, wildfires aren’t confined to North America. Thousands of miles away, Russian authorities have declared multiple states of emergency as blazes have scorched tens of thousands of acres, including in the Siberian Arctic.

Fires blaze above the Arctic Circle in Russia’s Sakha Republic, as seen in this image acquired by the Sentinel-2 satellite on July 12, 2024. The image is about 50 miles wide. (Credit: Modified Copernicus Sentinel data, processed by Pierre Markuse)

On July 18, 2024, Russia’s Federal Forestry Agency reported 69 fires burning across 1,069 square miles in the Sakha region of northern Russia alone.

Blazes in this region typically are sparked by dry lightning. “Fires are a natural part of boreal and high Arctic landscapes in Sakha and the broader Siberian Arctic,” says Kevin Smith, a U.S. Forest Service scientist quoted in a NASA Earth Observatory story. “However, the frequency, severity, and area encompassed by current wildfire conditions are truly striking.”

Smith is co-author of a 2022 analysis that found a three-fold increase in the number of fires in the Siberian Arctic, and more than a doubling in the total area burned, between 2000–2010 and 2010–2020.

%20(2)%20(1).jpg)

Discussion about this post