Venezuelans go to the polls Sunday to elect a president between incumbent Nicolas Maduro and rival Edmundo Gonzalez Urrutia, in a tense atmosphere marked by the last-minute barring of international observers and complaints of widespread opposition repression.

Gonzalez Urrutia has consistently polled ahead in the race, with majority support among both genders and all age groups. Fixing the country’s devastated economy is by far voters’ top priority.

Polling will take place on what would have been the 70th birthday of Maduro’s socialist predecessor and mentor Hugo Chavez, after whom the ruling “Chavismo” political movement was named.

Polls open for 12 hours at 6:00 am local time (1000 GMT) and results are expected late at night.

There are ten candidates, but only two with significant polling numbers.

Maduro, 61, is seeking a third six-year term amid warnings locally and abroad of increasing authoritarianism. Observers say the regime is holding more than 305 “political prisoners” and has arrested 135 opposition backers since January.

Maduro’s last re-election, in 2018, was rejected as a sham by dozens of Western and Latin American countries. The opposition boycotted that vote.

This time, the opposition has coalesced around ex-diplomat Gonzalez Urrutia, 74, heading the ticket in place of the wildly popular Maria Corina Machado.

Machado was barred from the process by institutions loyal to Maduro, but she has campaigned far and wide for her stand-in.

Some 21 million of an estimated 30 million Venezuelans are registered to cast a ballot at 30,000 polling stations countrywide.

But expert analysis puts the real number of eligible voters at closer to 17 million, taking into account outdated census data and an estimated seven million people having emigrated in recent years.

Fewer than 70,000 Venezuelans are registered to vote abroad.

Analysts say the higher the turnout, the harder it will be for the regime to fraudulently deny an opposition win.

Venezuela’s CNE electoral council, which oversees the vote, comprises five members, three of them pro-regime and two — or one, according to some critics — in the opposition camp.

There is little doubt about the allegiances of its president, Elvis Amoroso, who in his previous job as comptroller general — the overseer of public funds — declared several opposition leaders ineligible to hold office.

He is under US sanctions.

Ballots are cast on machines that experts say are difficult to manipulate — with interference more likely to come in the form of incentives or obstacles to voting.

Each machine prints out a paper receipt, while the electronic votes are sent directly to a centralized CNE database.

The opposition is deploying some 90,000 volunteer election monitors countrywide.

The government has announced the deployment of tens of thousands of security force members to keep the peace and enforce ramped-up border control, a two-day ban on alcohol sales, and a prohibition on public gatherings and protests.

The allegiance of the military is a key question in the election, with Maduro counting its leadership among his backers in a system of political patronage.

For his part, Gonzalez Urrutia has called on the army to respect and enforce the election outcome.

During Maduro’s second term, several Latin American countries have made a shift from the political right to the left — notably Brazil, Colombia and Chile.

And while ties with these countries have improved, their leaders have nevertheless added to recent pressure on Maduro for free and fair elections.

Brazil’s Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva criticized his counterpart’s threats of a “bloodbath” if he loses, saying: “Maduro has to learn: if you win, you stay (in power). If you lose, you go.”

The United States has insisted that the lifting of its sanctions in place since 2019 depends on a fair vote.

But it is keen, as is Caracas, for a loosening of punitive measures against the petrostate’s critical but severely weakened oil sector at a time of great pressure on crude prices with ongoing wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.

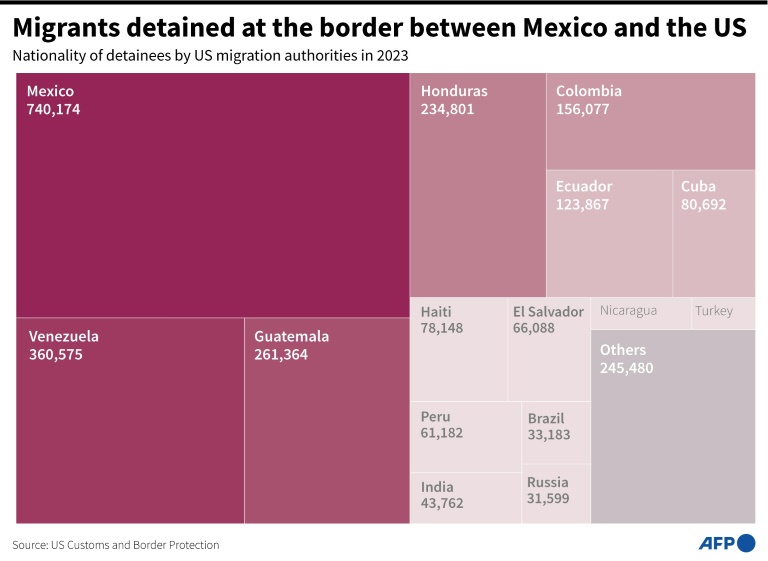

Venezuela has also been a major source of migration pressure on the southern US border, a situation experts say will only worsen in the event of a post-election political crisis.

AFP

AFP

Discussion about this post