Recreation of the Neolithic settlement of La Draga (Banyoles, Girona). Credit: Raul Soteras (German Archaeological Institute/University of Basel)

Research reveals that Neolithic farmers in Western Europe, particularly at La Draga, employed advanced cereal cultivation methods, reflecting a significant evolution from earlier agricultural methods that originated in the Middle East.

A team of researchers led by the University of Barcelona has uncovered new insights into the advent and expansion of agriculture during the Neolithic period in Western Europe. They found that nearly 7,000 years ago, the first farmers in the western Mediterranean used advanced agricultural practices similar to those seen today, selecting the most fertile land available, cultivating cereal varieties very similar to today’s, and making sparing use of domestic animal feces.

The study, recently published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), reconstructs the environmental conditions, crop management practices, and the characteristics of the plants that existed when agriculture appeared in Western Europe, referencing the site of La Draga (Banyoles, Girona, Spain), one of the most significant and complex sites on the Iberian Peninsula, as well as including data on sixteen other sites from the beginnings of agriculture in the region.

Their findings reveal that, at the time of its appearance on the Iberian Peninsula, agriculture had already achieved a consolidated level in agricultural techniques for growing cereals, suggesting an evolution throughout its migration across Europe of the methods and genetic material originating from the fertile crescent, the cradle of the Neolithic revolution in the Middle East.

On the Iberian Peninsula, agriculture had already achieved a consolidated level in agricultural techniques for growing cereals. Credit: Salvador Comalat (Archaeological Museum of Banyoles)

Experts from the University of Lleida (UdL) and the joint research unit CTFC-Agrotecnio, the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), the Universitat de València, the University of Basel (Switzerland), the Agri-Food Research and Technology Centre of Aragon (CITA) and the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) also participate in the article. The excavations in La Draga are coordinated by the Archaeological Museum of Banyoles, within the framework of the four-yearly archaeological excavation projects of the Department of Culture of the Government of Catalonia.

Archaeological Insights from La Draga

Since its appearance nearly twelve thousand years ago in the territories of the so-called fertile crescent, agriculture has transformed the relationship with the natural environment and the socio-economic structure of human populations. Now, the team has applied palaeoenvironmental and archaeobotanical reconstruction techniques to identify the conditions in the village of La Draga when agriculture emerged.

Located on the eastern shore of Lake Banyoles, it is one of the oldest settlements of farmers and stockbreeders in the north-east of the Iberian Peninsula (5200-4800 BC) and an extraordinary testimony to the first farming and stockbreeding societies in the Iberian Peninsula. To give a regional dimension to the study, cereal data from other Neolithic sites in the Iberian Peninsula and southern France have also been examined.

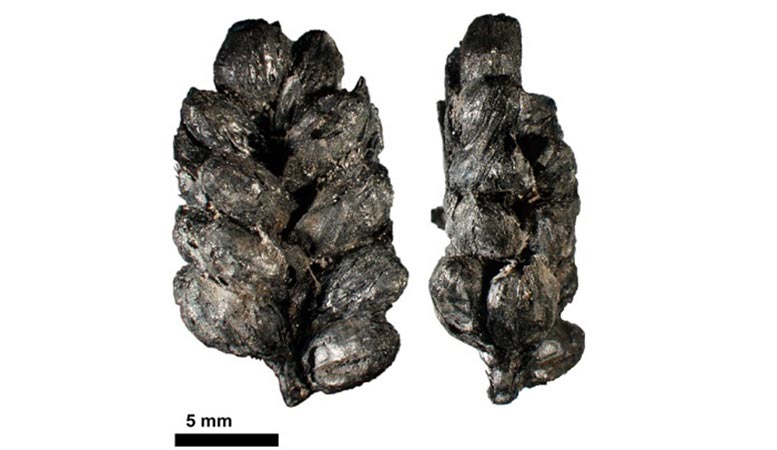

In this archaeological site, the most frequently found remains are carbonized cereal grains. Credit: Ferran Antolín (German Archaeological Institute/University of Basel)

The Agronomic Practices of Neolithic Farmers

Although it was pioneering agriculture — it began in previously uncultivated areas — “the growing conditions seem to have been favourable, possibly due to a deliberate choice by the farmers of the most suitable land. The crops do not seem too different from the traditional varieties that have been cultivated in the following millennia,” says first author Professor Josep Lluís Araus from the Faculty of Biology at the University of Barcelona, who is also a member of Agrotechnio, the CERCA Centre for Research in Agrotechnology.

In the study, Araus led the reconstruction of the agronomic conditions and characteristics of the crops based on the analysis of the samples collected and identified by the archaeobotanists of the UAB, the DAI, and the University of Basel.

The main source of information for studying agricultural practices in prehistoric times “are the archaeobotanical remains (seeds and fruits) that we find in the archaeological deposits we excavate. The most frequently found remains are carbonized cereal grains. Thus, isotopic studies on these remains allow us to open an alternative interpretative line to characterize past agricultural practices,” notes Ferran Antolín, from the DAI.

Professor Josep Lluís Araus, from the Faculty of Biology at the University of Barcelona and member of Agrotechnio, CERCA Centre for Research in Agrotechnology. Credit: University of Barcelona

Durum wheat and poppy are the DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2401065121

Discussion about this post