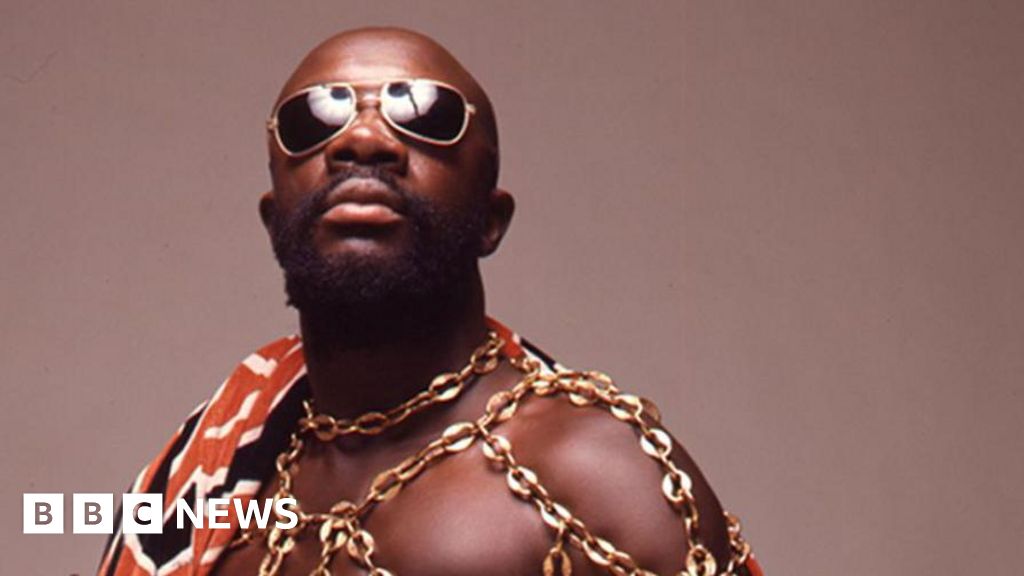

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe family of the late soul singer Isaac Hayes has ordered Donald Trump to stop playing the star’s song Hold On, I’m Coming at his campaign rallies.

A letter sent to Trump and his team, and shared by Hayes’ son on social media, threatens to sue the former US President if he does not comply by 16 August.

The family is also demanding $3m (£2.4m) in licensing fees for the campaign’s repeated use of the song between 2022 and 2024.

The song, which was made famous by soul duo Sam and Dave, is a regular feature of Trump’s rallies, often playing before and after his speeches.

Hayes composed the song in 1966 with Dave Porter, when he was a staff writer at Stax Records. He went on to become a Grammy and Oscar-winner in his own right, with hits like Shaft and Walk On By.

In their legal letter, Hayes’ family claimed to have “asked repeatedly” for Trump to stop using the song. They go on to cite 134 occasions on which the campaign went ahead anyway.

Their lawyer, James Walker, alleged that the Trump campaign has “wilfully and brazenly engaged in copyright infringement”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe went on to demand that the campaign remove any videos featuring the song, and issue a full statement acknowledging that Hayes’ family have not “authorised, endorsed or permitted” the use of his music.

Walker added that the requested $3m settlement is a “heavily discounted” figure, due to the frequency with which the campaign has played Hold On, I’m Coming.

The letter also stated that if a resolution was not made and a lawsuit was issued, the Hayes family would demand damages of $150,000 per use of the song – amounting to more than $20m (£15.7m).

The Trump campaign has yet to respond to the letter or the threat of legal action.

The Hayes family previously criticised Trump for playing Hold On, I’m Coming at a National Rifle Association convention, less than a week after the Uvalde school shooting in 2022, which claimed the lives of 19 people.

“Our condolences go out to the victims and families of Uvalde and mass shooting victims everywhere,” they wrote at the time.

Porter, the song’s co-writer, also wrote: “I did not and would not approve of them using the song for any of his purposes.”

Meanwhile, Sam Porter – who sang the original hit recording – objected to Barack Obama using the song in his 2008 presidential campaign.

“I have not agreed to endorse you for the highest office in our land,” he said in a statement at the time.

“My vote is a very private matter between myself and the ballot box,” he added.

Artist protests multiply

On Sunday, Hayes’ son, Isaac Hayes III, elaborated on his objections to the Trump campaign.

“Donald Trump epitomises a lack of integrity and class, not only through his continuous use of my father’s music without permission but also through his history of sexual abuse against women and his racist rhetoric,” he wrote on Instagram.

“This behaviour will no longer be tolerated, and we will take swift action to put an end to it.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Hayes family are the latest in a long line of musicians to complain about the Trump campaign.

The Beatles, Neil Young, Adele, Bruce Springsteen, Sinead O’Connor and Aerosmith are among the artists who have issued the politician with cease-and-desist orders.

In fact, the list of artists who have protested is so lengthy that the topic has its own Wikipedia page.

On Saturday, Celine Dion’s team also protested against the use of her track My Heart Will Go On at a rally in Montana.

“In no way is this use authorised, and Celine Dion does not endorse this or any similar use,” a statement read.

“And really, THAT song?”, it added – alluding to the fact that the track was recorded for the film Titanic, about a sinking ship.

However, musicians have only had limited success in stopping politicians from using their music.

In the US, campaigns are required to obtain a Political Entities License from the music rights body BMI, which gives them access to more than 20 million tracks for use in their rallies.

Artists and publishers can ask for their music to be withdrawn from the list, but it seems that organisers rarely check the database to ensure they have clearance.

“They don’t care as much about artists’ rights as perhaps you’d want,” said Larry Iser, a lawyer who represented Jackson Browne when he sued Republican candidate John McCain for one of his songs in a 2008 commercial. (The case was later settled).

“It’s not just the Trump campaign,” Iser told Billboard magazine. “Most political campaigns aren’t keen about just taking the song down.”

Cases rarely, if ever, head to court – with both sides typically backing down after a flurry of legal letters.

Discussion about this post