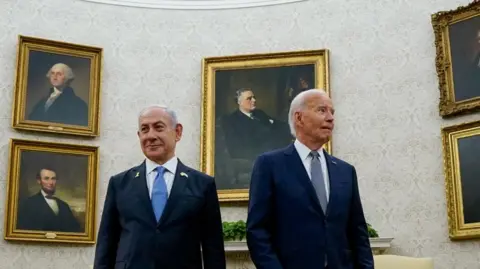

Reuters

ReutersEarlier this week, on live television, the mother of one of the Israeli hostages held in Gaza made an offer to the Hamas leader, Yahya Sinwar: Release all 109 hostages – dead and alive – in exchange for the children of Israel’s security chiefs.

But Ditza Or, whose son Avinatan was kidnapped from the Nova music festival during the 7 October attacks, wasn’t pushing for Israel’s leaders to sign a ceasefire deal – she was pushing them to fight Hamas harder.

Ms Or, and a handful of other pro-war hostage families, are unlikely allies of Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who is now under immense pressure from his US ally, his security chiefs and even his own defence minister to be more flexible and reach a deal.

Leaked reports of a recent phone call with his most important ally suggested that US President Joe Biden told the Israeli leader at one point to “stop bullshitting” him. The implication: that Mr Netanyahu didn’t want a deal at all.

As negotiations limped on in Cairo this week, aimed at bridging the gaps between Israel and Hamas, leaks to Israeli media suggest that the gaps between Mr Netanyahu and his own negotiators and defence chiefs are getting wider.

According to Dana Weiss, chief political analyst for Israel’s TV Channel 12, the prime minister privately accused key negotiators and security chiefs of “weakness”, presenting himself as standing alone in defence of Israel’s security interests.

They have different approaches to the urgency of a deal, she says, and one reason for that is the differing level of responsibility each feels.

“The military establishment feel guilty about 7 October, and feel a moral duty to bring back the hostages,” she explained. “Our government, our ministers and especially Prime Minister Netanyahu don’t feel personally responsible for 7 October, they put the blame totally on the military establishment, and therefore do not feel that same sense of urgency to go ahead with a deal.”

Mr Netanyahu has said that getting the hostages home is his second priority in the war – behind victory over Hamas, and has emphasised his commitment to preserve Israel’s security “in the face of major domestic and foreign pressure”.

The man who once cherished his image as Israel’s ‘Mr Security’ appears to be playing to it again, 10 months after that image was shattered by the 7 October attacks.

A key sticking point in negotiations is whether Israeli forces withdraw from a strip of land along Gaza’s border with Egypt, known as the Philadelphi Corridor.

Mr Netanyahu appears to be sticking hard to a “red line” of keeping an Israeli military presence there, citing Israel’s security needs, despite leaks suggesting that his negotiators believe it is a “deal-breaker”.

Senior Hamas figure Hussam Badran told the BBC on Friday that the group would accept nothing less than the withdrawal of Israeli forces, and that Mr Netanyahu’s position showed that he did not want an agreement, but was “manipulat[ing] through empty rounds of negotiations to gain time”.

Hamas is widely seen as facing tough questions over what Gaza or the Palestinians have gained from the October attacks, after more than 10 months of bombing and displacement.

Compromises on prisoner exchanges are seen as easier for the group to swallow than accepting the continued presence of Israel’s army in Gaza, and checkpoints for residents moving north.

Egypt is also understood to be refusing any deal that does not have Palestinians in charge on the other side of their shared border.

MOHAMMED SABER/EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

MOHAMMED SABER/EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock Hamas has not formally joined the current round of talks, and many believe Mr Sinwar’s own priority is keeping the Gaza War going in order to spark a regional conflict, which would put enormous pressure on Israel, and – the reasoning goes -force its prime minister into greater concessions to end it.

The risks of a wider escalation – amid threats from Iran and Hezbollah – are one reason Washington is pressing hard for a deal. The US is three months away from a presidential election, and President Biden’s administration believes a ceasefire in Gaza would help calm the region.

The political analyst, Dana Weiss, says that Israel’s Defence Minister Yoav Gallant agrees that if Israel does not take the path of a ceasefire deal – even temporarily – then it will be on a sure path to escalation.

“For the prime minister, it’s totally the opposite,” she says. “He answers: No, if we go ahead and cave to Sinwar now, Hezbollah and Iran see that we’re weak. We have to finish the task with Hamas, to prevent the war.”

But, she says, Mr Netanyahu also has domestic political incentives to stall the negotiations. Among those incentives is the fact that, after months of abysmal approval ratings, he is now rising again in opinion polls.

Several surveys have recently placed him at the top of respondents’ voting intentions, both in terms of his right-wing party, Likud, and his own personal profile as leader – results that were unthinkable a few months ago.

All eyes are now on the next scheduled talks, due to take place on Sunday. In the meantime, Egypt has reportedly agreed to share Israel’s latest proposal for the border area with Hamas.

Mediators insist a deal is still possible, but hopes on all sides appear to be shrinking.

After meeting the Israeli prime minister today, Ella Ben Ami, the daughter of another Israeli hostage, said she looked Benjamin Netanyahu in the eye and asked him to promise to do everything and not give up until they return.

She was left, she said, with “a heavy and difficult feeling that this isn’t going to happen soon”.

The clock is ticking on these negotiations: for Gaza’s people, for the Israeli hostages still held there in tunnels, for the region as a whole.

But for Mr Sinwar and Mr Netanyahu, perhaps the most powerful weapon they have in this war is time.

Discussion about this post