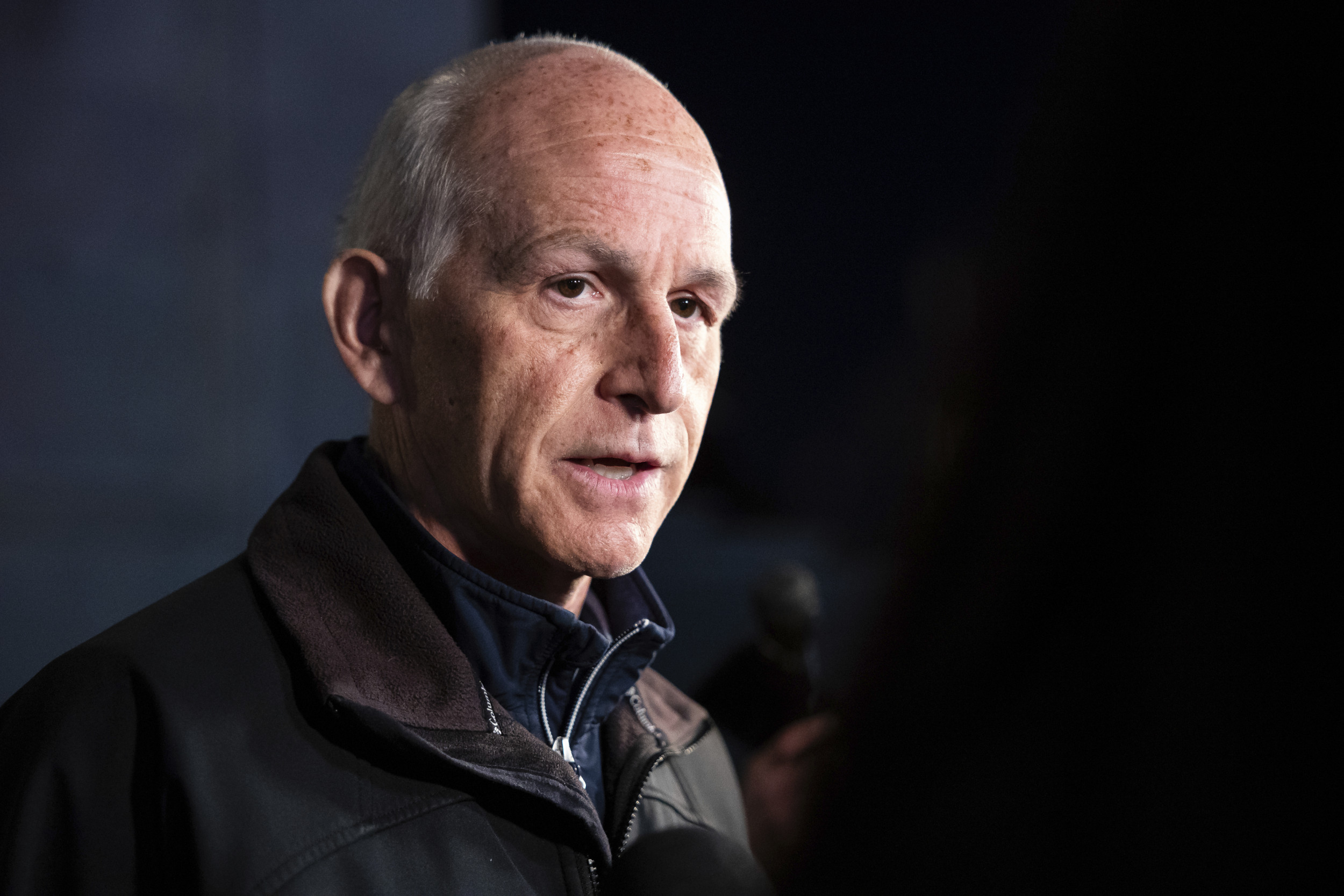

Over the past few months, officials responsible for running the federal government’s investigation into “unidentified anomalous phenomena” or UAP—the new term for UFOs—have been speaking publicly about their findings. In March, the All-Domain Anomaly Resolution Office (AARO) released its first report on historical UFO sightings, concluding that it “has not discovered any empirical evidence that any sighting of a UAP represented off-world technology or the existence a classified program that had not been properly reported to Congress.” AARO’s Acting Director Tim Phillips reiterated this point in a news conference. Meanwhile, former Director Sean Kirkpatrick has gone on record to criticize conspiracy theorists for making baseless claims, and, in a recent interview, he expressed his exasperation at threats made to him and his family. None of this, however, had done anything to quell demands by some members of Congress and disclosure advocates for the U.S. government to release all its classified documents involving unidentified flying objects.

How did it come to this? For over a decade and a half, few if any mainstream media outlets or politicians had made any mention of UFOs. But after a December 2017 article in the New York Times contended that the Department of Defense had run a secret UFO investigation program between 2007 and 2012, that changed. Since then, the topic has been examined in congressional hearings and has assumed a prominent place on social media, podcasts, and cable television.

To explain this change requires looking back to the history of interest in UFOs. UFOs first became part of popular culture after a private pilot by the name of Kenneth Arnold spotted some disk-like objects flying in formation near Mt. Rainier in Washington state in June 1947. Newspapers at the time dubbed them “flying saucers,” and over that summer, hundreds of Americans reported seeing them.

World War II had just ended. The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union was underway. It would soon involve an unprecedented arms race that included atomic weapons, intercontinental ballistic missiles, surveillance balloons, high-altitude aircraft, and satellites. A lot was going on over the heads of people across the world, and for most of them, it was an unnerving development.

Read More: The UFO Congressional Hearing Was ‘Insulting,’ a top Pentagon Official Says

So, when speculation turned to who might be behind the mysterious flying saucers, attention was initially drawn to either the U.S. and Soviet militaries or the possibility that it all could be chalked up to war hysteria. Over the course of the 1950s, however, more and more people turned to the prospect that aliens were responsible, given the remarkable shapes and bizarre characteristics of the objects being reported. The widely presumed explanation for the peculiar timing of their visits was that extraterrestrial beings had been observing Earth from afar, had seen that we on Earth had unlocked the secret to nuclear power, and were now concerned about the dangers it held for us and the entire solar system.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Air Force began investigating sightings soon after the Arnold sighting. It would continue to do so until 1969. Time and again, officials told the public that UFOs posed no national security threat and dismissed the reports of witnesses as cases of misperception. Venus, lenticular clouds, temperature inversions, birds, weather balloons: all were flagged as likely culprits.

UFO enthusiasts weren’t buying it. From the 1950s on, civilian groups studying the phenomenon insisted authorities were hiding the truth that flying saucers were the work of aliens, and that the government might well have spacecrafts and their occupants in custody. And so began the efforts of ufologists, as they came to be called, to clamor for full disclosure and to lobby Congress to hold open hearings. A few officials and experts did testify on the subject on two occasions in the 1960s, and in 1994 the Air Force released a lengthy report on claims of a crashed saucer in Roswell, N.M., in 1947. Despite this and the release of thousands of formerly classified documents by the United States, Great Britain, and numerous other countries since the start of the new century, advocates for greater transparency have remained unconvinced by government denials.

All the while, civilian researchers took it upon themselves to begin investigating cases on their own. By the 1960s and 1970s, some believed a pattern in reports was emerging of UFO sightings near military bases and nuclear facilities, and of witnesses being intimidated to change their stories by ominous “men in black.” The 1980s and 1990s then saw the growing prominence of tales of alien abduction, according to which individuals were being taken from their homes and subjected to examinations, experiments, and even insemination. These dark tales eventually became a staple of the hit television show The X-Files starting in 1993, portraying an elaborate conspiracy between the U.S. government and fiendish aliens.

The X-Files was less an emblem of the heyday of fascination with UFOs as it was of its swan song. As the Soviet Union dissolved and the Cold War faded away, so too did much of the popular interest in unidentified flying objects and alien visitors. From the late-1990s through the first dozen years of the 21st century, membership in UFO organizations declined, some groups closed, and newsletters and publications disappeared. The rise of the internet steered interest in UFOs into niche, online forums. At the same time, 9/11 and its legacy replaced anxieties over nuclear winter and cloak and dagger espionage with fears of unpredictable acts of terrorism and sleeper cells. In movies and television, aliens made way for vampires and zombies, creatures who could be—or once were—human beings like us and required no complex technology to pose a threat. By 2012, even enthusiasts openly wondered whether the obsession with UFOs had finally come to an end.

Read More: How NASA Got a ‘UFO Czar’—And Why it Matters

And now, they are back, this time set against the backdrop of drone warfare, science skepticism, and criticism about the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. The name may be different, but the UFO brand is the same.

These mysteries seem like expressions of our own terrestrial worries: that national security may be threatened by foreign adversaries with advanced technology. Meanwhile, we wonder if beings from other worlds are observing us—to what end, no one knows. And the calls for government disclosure are just as shrill as they were decades before. The label “UAP” may have been created to escape the associations “UFO” had had with wild speculation and pop culture, but history is not so easily erased or escaped.

What connects today’s passion for UFOs with that of the past is a consuming feeling of vulnerability on the part of many Americans. World War II and the Cold War helped introduce the world not only to powerful weapons of mass destruction but also to government programs designed at once to build them and keep them secret. This sense that unaccountable looming powers are capable of inventing technologies that neither we nor they may be able to control—just think of artificial intelligence today—is both the past and present of the UFO phenomenon. And likely its future.

Greg Eghigian is a Professor of History and Bioethics at Pennsylvania State University and author of After the Flying Saucers Came: A Global History of the UFO Phenomenon.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

Discussion about this post