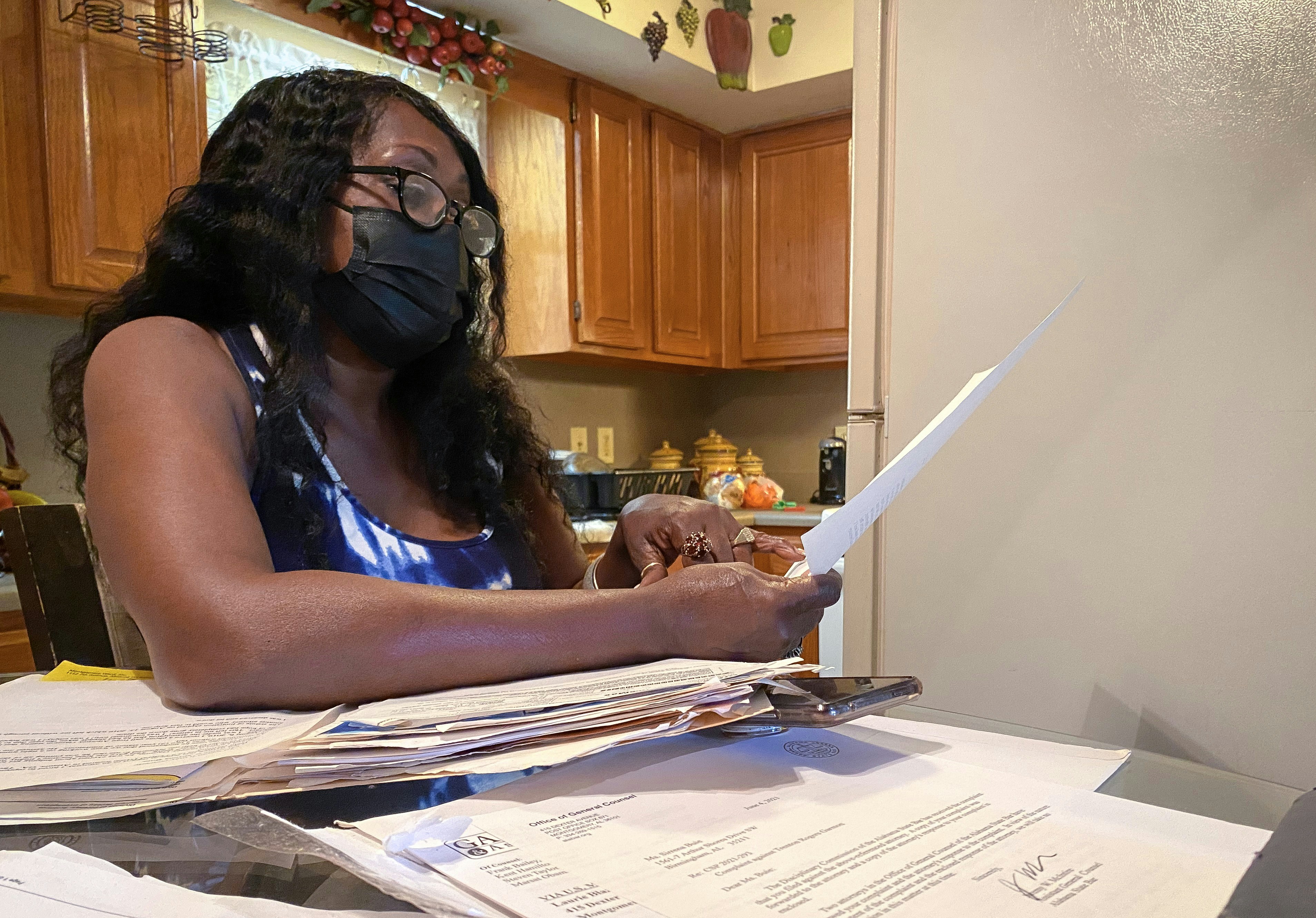

Sirrena Buie sat at her kitchen table, scrolling through her texts. She was looking for a message from a man who might have information related to her son’s death. Twenty-six-year-old Kedric Buie had died five years earlier at the U.S. Penitentiary in Atlanta — found “unresponsive,” in the clinical parlance of the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Officials said that he’d died of a heart attack. But his mother was convinced that he had been killed.

After pursuing legal avenues that went nowhere, Sirrena turned to social media, where she posted videos telling her story. She urged anyone who might know something to come forward. This man was one of several people who had recently offered to help. He said he had known her son — and “that he knows some people that know some people that’s supposed to get in contact with me about this,” Sirrena said. In her quest for the truth, even vague tips were a lifeline. She found the man’s message and pulled it up for me to see. “Atlanta is a bad place that did a lot of bad things to good people,” he wrote. “They did your son bad and I know this.”

I met Sirrena Buie on August 1 at her home just south of Birmingham, Alabama. Employed at the deli counter at a Publix supermarket, she also does freelance catering, posting photos of her colorful fruit platters on TikTok. Her account is otherwise full of family photos, pictures of Kedric set to music, and video updates describing her fight for justice. “They expected for me to give up,” she said in a video posted in May. “But I haven’t.”

Sirrena Buie holds a framed photo of her son Kedric Buie outside her home in Birmingham, Ala., on Aug. 1, 2022.

Photo: Liliana Segura/The Intercept

Buie always starts her story the same way. It was 10:50 a.m. on August 13, 2017, and she was sitting at the same kitchen table with her then-husband. They were eating Brussels sprouts. When her phone rang, she almost didn’t answer. “I thought it was a bill collector or something,” she told me. Instead, it was a woman calling from USP Atlanta. The woman told her that Kedric had been found dead in his cell. At first it didn’t register. “I just talked to my son yesterday,” Buie remembers saying. “And y’all found him dead?”

“I couldn’t talk. I couldn’t do nothing.” She walked toward the bathroom but broke down in the hallway. The woman said she would call back later so that Buie could compose herself. “And I said OK.” But when the woman called back, she had no information. She couldn’t offer any details about what had happened to Kedric or even the name of the hospital where he had been taken. She told Buie not to come to Georgia.

The next hours were chaotic. Kedric’s identical twin brother, Kemon, heard the news from their father and got a ride to Buie’s home, jumping out of the car while it was still moving and running toward the house. “He could not pull himself together,” she said. Perhaps her most vivid memory was finding out that her son’s body had finally arrived in Birmingham 10 days after his death. When she saw Kedric, he looked severely swollen. His hands were clenched, and there appeared to be a gash on his forehead. “It didn’t seem real,” Buie said.

Everyone wanted to know what had happened to Kedric. But Buie could not answer their questions. As Christmas approached, she sent an open records request to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, which provided her son’s autopsy report. The five-page document raised more questions than answers. It said that Kedric had received his breakfast on the morning of August 13 and was found “unresponsive” in his cell an hour later, minutes before 8 a.m. At 9:05 he arrived at the Atlanta Medical Center, where he was pronounced dead.

A Georgia Bureau of Investigation medical examiner conducted the autopsy two days later. Kedric’s body had arrived at his office dressed in a “red inmate jumpsuit,” two pairs of boxer shorts, and only one shoe. The medical examiner concluded that the cause of death was “hypertensive and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” based on Kedric’s enlarged heart, a severely clogged artery, and the fact that he was “morbidly obese.” The manner of death was classified as “due to natural causes.”

But the autopsy report also contained information that alarmed Buie. On the first page were the words “EVIDENCE OF ACUTE INJURY,” followed by technical descriptions of wounds to Kedric’s back and scalp. A summary of findings listed “blunt trauma of the head” and “blunt force trauma of the torso and left lower extremity.” Although the document noted that there were “no life-threatening injuries,” the words left Buie cold. When she later spoke to the medical examiner, he told her that the injuries had occurred close to the time of Kedric’s death. He insisted that her son had died of a heart attack. But “he could not explain the trauma to my son’s body,” she said. He also discouraged her from seeking the autopsy photos, saying “that I needed to remember him the way I remember him.” She found this suspicious. If her son died from a heart attack, why should the photos be so upsetting?

On the advice of a friend, Buie contacted an independent pathologist who represented the families of people who had died in law enforcement custody. He told her that he did not believe the official findings, she said. Not long afterward, a high-profile lawyer agreed to represent her in a wrongful death suit. Over email in June 2019, he told her that the case was “really taking shape.” The lawyer said the pathologist was firm that Kedric had been beaten up — and that the official story was false. “He was very clear,” the lawyer wrote. “He said, ‘You know how they do.’”

Photo: Liliana Segura/The Intercept

The Atlanta Way

Buie is one of countless family members still fighting for answers years after their loved ones died of “natural causes” in Bureau of Prisons custody. A lack of information from BOP officials often compounds the confusion and anguish. This struggle became especially pronounced during the Covid-19 pandemic, which heightened the frustrations of family members navigating a prison bureaucracy whose lack of transparency is notorious.

The BOP routinely sends press releases documenting deaths in its facilities but provides little information beyond a decedent’s name, age, and the crime for which they were sent to prison. Although media outlets sometimes report on such cases, people are often imprisoned far from home, making their deaths easier for local news to overlook. Last month alone, the BOP’s Information, Policy, and Public Affairs Division sent five media notices about deaths at four different federal prisons, with the deceased ranging from 37 to 71 years old.

In an email, BOP spokesperson Scott Taylor confirmed that Kedric “passed away on August 13, 2017, while in custody at the United States Penitentiary Atlanta. However, this office does not provide additional information on deceased inmates.” According to the BOP, his death was one of six at USP Atlanta in 2017. The penitentiary has a reputation for being uniquely dangerous for residents and employees alike. Media reports have long exposed the medium-security prison as a cesspool of drugs, corruption, and violence. The year Kedric died, a federal complaint described how the Atlanta Police Department had spent years “investigating instances of inmates temporarily escaping from the prison camp at USP Atlanta and frequently returning to the camp with contraband.” In 2018, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “a prisoner used a cellphone to record a 49-minute long Facebook Live session, where he bragged that he had murdered a man and got away with it.”

USP Atlanta was the subject of a U.S. Senate hearing on July 26, a week before I met Buie. The penitentiary has been under investigation by the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs since September. Investigators uncovered thousands of pages of internal reports along with explosive accounts from dozens of former employees. As my colleague Akela Lacey reported, the hearing featured testimony from the head of the BOP himself and painted “a damning picture of a bloated federal prison system run by well-informed and willfully inactive leaders.”

Presiding over the hearing was Sen. Jon Ossoff, D-Ga., chair of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. In his opening statement, he decried the “stunning long-term failures” at USP Atlanta, whose staff “engaged in misconduct with impunity and, according to BOP’s own internal investigations, lacked regard for human life.” Subsequent witnesses described the prison as so out of control that the lawlessness and lack of accountability had been given a name: “the Atlanta way.”

A whistleblower who worked as the chief psychologist at USP Atlanta from 2018 to 2021 testified that the inhumane conditions contributed to a disproportionate number of suicides at the prison. “In the roughly four years, eight inmates at USP Atlanta died by suicide, two prior to my arrival and six during my tenure,” she said. “To put this into perspective, federal prisons typically see between one and three suicides over a five-year period.” A Georgia federal defender said she had seen her clients become emaciated during their time at the facility due to the spoiled and inedible food they received. And a former prison administrator said she was forced into early retirement after trying to address gross misconduct at the prison — including staffers’ physical abuse of incarcerated people.

The testimony supported what I had repeatedly been told about USP Atlanta while covering conditions at federal facilities in the early days of the pandemic. One formerly incarcerated man called it “unlivable,” a crumbling hellhole filled with cockroaches. Several others described correctional officers as openly cruel. “I heard an inmate complain that he was having trouble breathing and the CO told him, ‘Good motherfucker, take short breaths,’” one man incarcerated at the prison wrote in a letter.

But the hearing did not include any witnesses who could describe how hard it was to get basic information after the death of a loved one at USP Atlanta. Although BOP protocol dictates that family notification is handled by the warden or a warden’s representative, Buie says no one from the warden’s office ever contacted her.

“I heard an inmate complain that he was having trouble breathing and the CO told him, ‘Good motherfucker, take short breaths.’”

Other families say the same thing. After 36-year-old Billy Joe Soliz died at USP Atlanta in 2020, his sister told a TV station in his hometown of Corpus Christi, Texas, that the warden had ignored calls from the family. “We’ve been trying to talk to the prison and trying to get ahold of the prison, and they will not answer the phone, they won’t contact us back,” she said. Like Kedric, Soliz was reportedly found “unresponsive” in his cell. And like Kedric, he seemed fine in his last phone call with his mother the day before he died.

Even those who examine the bodies of people who die in federal custody say information can be sparse. Forensic pathologist Kris Sperry, who was Georgia’s chief medical examiner from 1997 to 2015, said the Georgia Bureau of Investigation does not have jurisdiction to investigate deaths at USP Atlanta. In the case of an obvious homicide, the FBI would take charge and send a representative to attend the autopsy. “But for nonhomicide deaths, you know, just somebody … found dead in his cell, no one ever came to the autopsy,” Sperry said. “The amount of information that we had was severely limited. We had to completely depend on what someone at the prison told us.” Although he sometimes received information about a person’s medical history from a prison hospital physician, it could be “almost impossible to get ahold of anyone at the prison to give us … answers about real basic stuff. Like when was he last seen alive? Silly things like that.”

At the hearing, Ossoff seemed particularly disturbed by the deaths of people who had not yet been convicted of any crime; many of those held at USP Atlanta are pretrial detainees. “We’re talking about human beings in the custody of the U.S. government,” he said. After grilling the outgoing director of the BOP, Michael Carvajal, for his failure to fix the problems at USP Atlanta, Ossoff expressed hope that change might be on the horizon. “There has got to be change at the Bureau of Prisons. And it has to happen right now. And with your departure and the arrival of a new director, I hope that moment has arrived.”

Kedric Buie during a visit with a loved one while incarcerated in federal prison.

Photo: Liliana Segura/The Intercept

A Verified Threat

Kedric Buie was not a pretrial detainee. Nor was he innocent of his crime. In 2009, at the age of 18, he and Kemon were arrested after carjacking a woman in a CVS parking lot in a Birmingham suburb. Along with a third man, they took the victim’s keys at gunpoint and forced her into the back of her Toyota 4Runner, releasing her a few minutes later, according to police.

Federal prosecutors conceded that the third man “was more of the instigator” and had recruited the brothers to help commit the crime. But the sentencing judge was angered by a statement Kedric made in court, in which he expressed remorse but also said he hoped to leave prison young enough to “play me some NFL football.” She sentenced him to 12 years and eight months in prison. Kemon received a shorter sentence and was released in 2016.

“I do hate that I’m punishing your family,” the judge told Kedric as she handed down his sentence. But he would still be a young man when he got out, she said. “This doesn’t have to be the end of your life.”

Prison records show that Kedric feared his time at USP Atlanta could become a death sentence. Last year a reporter helped Sirrena Buie obtain a case file revealing that Kedric had asked to be placed in protective custody less than two months before he died. The records showed the prison had conducted an investigation in June 2017, which concluded that “a verified threat to inmate Buie’s safety does exist” and “he is to be considered a verified protection case at this facility.”

Kedric feared his time at USP Atlanta could become a death sentence.

“I was devastated,” Buie said. She knew Kedric did not like to tell her things that would make her worry. But she was also skeptical. The report was heavily redacted and contained information that only raised more questions. One page noted that Kedric had engaged in “self-harm” via an unnamed toxic substance two weeks before he died. Prison staff also claimed to find black tar heroin in his cell on the day of his death, but the drug was not in his system. Buie felt the prison was seeking to blame Kedric for his own death.

According to people who had contacted her over the years saying they had information about Kedric’s death, the prevailing rumor at USP Atlanta was that he had been killed by a guard. In her own conversations with her son, he complained about one guard who had repeatedly spit into his food. “He said, ‘Mom, they do everything, they do anything,’” she recalled. “He said, ‘It’s not the inmates, it’s the officers.’” But according to a lieutenant who reportedly interviewed Kedric inside a special housing unit where he was temporarily isolated, “inmate Buie is a known thief within his housing unit,” which had made him a target among “Muslim inmates and inmates from Alabama.” Although Kedric was both Muslim and from Alabama, “both inmate communities indicate Buie has brought unwanted attention, and will have to deal with the consequences of his actions if he returns to the unit.”

The file does not reveal why, if there was a verified threat against Kedric, he would have been returned to his unit, where he died just over a month later. But it is consistent with descriptions of staff at USP Atlanta showing indifference to the safety and well-being of those in their custody. “They knew what was going on, and they did not care,” Buie said.

In the first few years following her son’s death, Buie hoped that a lawsuit might be the best way to get answers from the BOP. She was especially optimistic that the independent medical examiner, Dr. Adel Shaker, would be able to prove that her son had been killed. In June 2019, her lawyer sent her a draft affidavit outlining Shaker’s tentative findings in the case. It said that Kedric had “died as a result of a blunt force trauma he suffered to the head.” But the affidavit was never signed, and the lawyer became mired in legal problems. Following multiple arrests in 2019, he pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct and public intoxication. In 2020 he made headlines for a drunken disturbance at a Florida hotel, where he was witnessed “berating two hotel patrons with racial slurs,” according to one news report. He is currently suspended from practicing in Alabama.

When we met in Birmingham, Buie told me that she had been unable to reach Shaker for a long time. He stopped answering her calls after her lawyer dropped the case. As it turned out, he too had been arrested. After going to work as the chief medical examiner in Nueces County, Texas, he became the subject of a criminal probe alleging sweeping violations of the Texas Occupations Code. The case is ongoing. In the meantime, a mother in Mobile, Alabama, accused Shaker of taking thousands of dollars to perform a private autopsy of her son, whom she suspected had been beaten to death. But she said the autopsy was never done. (Shaker denied the allegations, telling reporters that she was simply unhappy with the results.)

In a brief phone call, Shaker said he did not recall Kedric’s case. But after reviewing the draft affidavit laying out his supposed findings, he said he had refused to sign the document because he never received sufficient materials to render an opinion one way or another. Although he remembered speaking to Buie, he denied ever telling her that her son’s death was a homicide.

Sperry, Georgia’s former chief medical examiner, said the findings in Kedric’s autopsy report point clearly to a heart attack. If Buie was told otherwise, it would not be the first time he had seen a grieving family member misled by an expert. “If you look hard enough, you can find a forensic pathologist who will agree with what you want him to agree to, as long as you write out a check,” he said. Buie never paid Shaker or her attorney any money. But when it comes to skewed autopsy results, law enforcement agencies are in a far more powerful position than families like hers. Flawed or biased autopsies have historically been used to convict the innocent or evade accountability, especially when the subjects are Black.

“I’m done with lawyers. Giving me money is not going to tell me what happened to my son.”

In a phone call, Dr. Colin Hebert, the pathologist who conducted Kedric’s autopsy for the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, stood by his findings. Hebert, who now works for the Fulton County Medical Examiner, confirmed that Kedric’s injuries occurred close to the time of his death. “I don’t know how they got there,” he said. But it was not unusual to see bruises on a person who died of cardiac arrest. In Kedric’s case, he peeled back the skin and subcutaneous fat in the places where he found bruising to assess the depth of the trauma and found nothing alarming. Photos of this process are graphic, he explained, which was “probably one of the reasons I discouraged the mom to see the photos.”

Buie has considered the possibility that her son died of a heart attack after being beaten rather than dying from a beating itself. But until she has a complete picture of the circumstances leading up to her son’s death, she will not accept anything authorities have to say. In the meantime, “I’m done with lawyers,” she said. She has never been especially interested in any money a potential lawsuit would bring: “Giving me money is not going to tell me what happened to my son.”

The day after I met Buie, the BOP swore in its new director, an official with a reformer’s reputation. “Together we will work to ensure that our correctional system is effective, safe, and humane for personnel and incarcerated persons,” Attorney General Merrick Garland said at the ceremony. Buie was unaware of the change. A new director would make little difference for her, she said. The system was not going to put anyone in charge who would give her answers about her son.

On Saturday, the fifth anniversary of Kedric’s death, Buie shared commemorative posts on TikTok, accompanied by “I Miss You” by Kim McCoy and “It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday” by Boyz II Men. She had hoped to go to Kedric’s gravesite that morning, but she was struggling. After the weekend, she would go back to seeking answers. As she once said in a video, if the BOP had been transparent from the start, maybe she would not still be doing all of this. But “right now, I want closure. I want to know every detail.”

Discussion about this post