Torrential rainfall from the remnants of Hurricane Helene capped off three days of extreme, unrelenting precipitation, which left catastrophic flooding and unimaginable damage in our Mountains and southern Foothills.

It was close to a worst-case scenario for western North Carolina as seemingly limitless tropical moisture, enhanced by interactions with the high terrain, yielded some of the highest rainfall totals – followed by some of the highest river levels, and the most severe flooding – ever observed across the region.

It’s no exaggeration to liken this to a Florence-level disaster for the Mountains, since the apparent rarity of the rainfall amounts and the impacts they produced – including large stretches of highways underwater and a plea from the NC Department of Transportation that “all roads in western NC should be considered closed” – were on par with eastern North Carolina’s worst hurricane from six years ago.

While the full extent of this event will take years to document – not to mention, to recover from – we can make an initial assessment of the factors that made for such extreme rainfall, the precipitation totals and other hazards, and how this storm compares with some of the worst for the Mountains and for our state as a whole.

The Setup for Relentless Rain

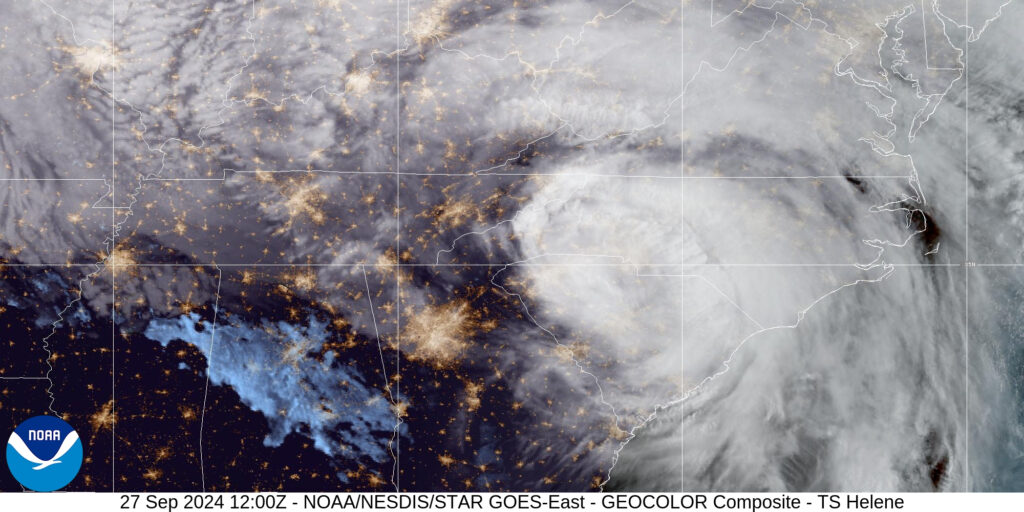

At 5 pm on Wednesday, September 25, Hurricane Helene was at Category-1 strength with its center just north of Cancun, Mexico, more than 500 miles and 30 hours away from its eventual landfall along the coast of Florida.

But it was already raining in Asheville by then, as a line of slow-moving showers along a stalled cold front – fed by tropical moisture from the fringes of Helene to the south – had set up from Atlanta through the southern Appalachians.

By midnight on Thursday, the Asheville Airport totaled 4.09 inches, and streamflows were already running at daily record high levels in upstream, upslope parts of the French Broad River basin.

The rain continued all day on Thursday as the frontal boundary had barely moved and Helene’s outer rain bands were closing in, adding even more moisture to the mix. More than nine inches fell that day across southern Yancey County.

As mountain streams became overrun with moisture, that water rushed down the rivers and into towns such as Asheville, all while the heaviest rain from Helene was just beginning to fall.

The storm’s impacts were especially long-lasting because of its massive size. It developed in a high-humidity environment over the warm Gulf of Mexico, which let it grow and strengthen unimpeded.

That also created a broad southeasterly circulation – with tropical storm-force winds extending more than 300 miles from the center as it impacted Florida – that pushed even more moisture up the saturated mountain slopes.

From the start of the precursor frontal showers on Wednesday evening to the heart of Helene moving through on Friday morning, it was one of the most incredible and impactful weather events our state has ever seen.

Extreme Totals and Flooding

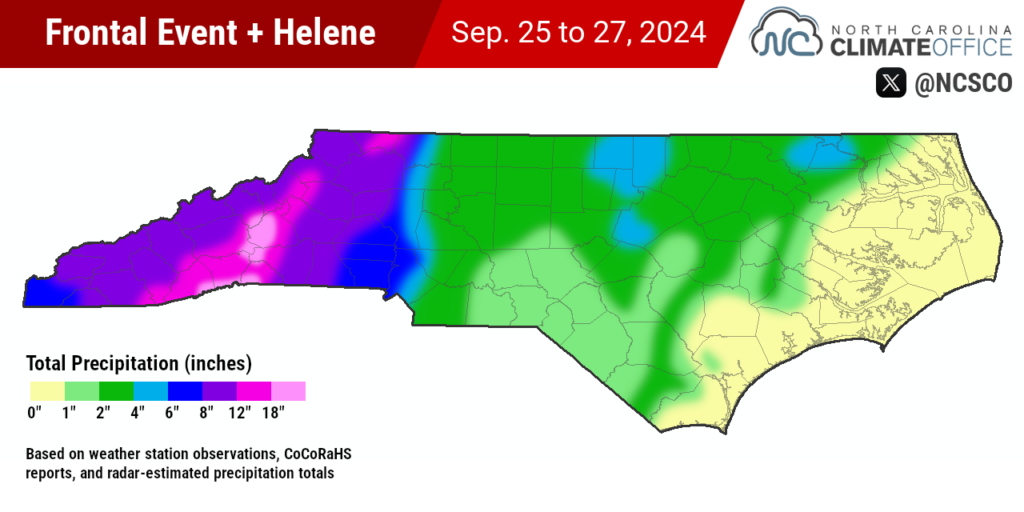

Over that three-day window from Wednesday, September 25 through Friday, September 27, rainfall totals exceeded eight inches across our Mountain region, with a foot or more falling in parts of Alleghany County and in a swath from Boone through Brevard.

More than 18 inches fell across southern Yancey County, western McDowell County, southeastern Buncombe County, and northwestern Rutherford County. That included 24.41 inches at our ECONet station on Mount Mitchell and 19.99 inches at our station on Bearwallow Mountain.

The highest apparent total from the event came from the North Carolina Forest Service’s RAWS station in Busick, with a three-day accumulation of 31.33 inches. While unvalidated at this point, radar estimates back up the potential for two feet of rain or more in Yancey County.

In addition to these automated weather stations, four CoCoRaHS observers recorded three-day totals of more than 20 inches: 24.12 inches in Spruce Pine, 22.36 inches in Foscoe, 22.12 inches south of Black Mountain, and 21.96 inches south of Hendersonville.

At least a dozen weather stations had their wettest three-day periods on record during this event, including the National Weather Service’s Cooperative Observer stations in Celo (19.98 inches), Sparta (17.29 inches), and Boone (16.67 inches).

The weather station at the Asheville Regional Airport lost communications on Friday morning, but up to that point, it had reported 13.98 inches – nearly three months’ worth of precipitation falling in less than three days.

That heavy rain sent the Watauga, Catawba, Swannanoa, and French Broad rivers near or above their major flood stages, and that rising water overwhelmed communities across the region.

Downtown Boone was inundated by several feet of flooding and emergency responders had conducted swift water rescues in Watauga County. Morganton suffered significant flooding as the Catawba River – which hit record levels just upstream – spilled over into the city.

In Buncombe County, officials reported “biblical devastation”, with Asheville largely inaccessible and water up to the rooftops in surrounding communities such as Swannanoa and Black Mountain.

Heavy rain along the Broad River basin sent a destructive wave of water, mud, and debris into the towns of Chimney Rock and Lake Lure, reducing homes and businesses to splinters. As that water crested the top and flowed around the side walls of the Lake Lure Dam, it prompted downstream evacuations in case of a dam failure.

Similar evacuations were requested downstream of the Waterville Dam in northern Haywood County and along parts of Mountain Island Lake as “large amounts of water” moved through the swollen Catawba River system.

And landslides or mudslides were evident on Interstate 40 in McDowell County and along the Tennessee border, as well as in countless rural corners of the Mountains such as the byways near Brevard, where the typical fall sights of scenic waterfalls and colorful foliage have been replaced by total destruction this year.

Wind and Tornadoes

With the exception of storm surge – and Florida was hit hard by that – Helene brought the full suite of hurricane impacts to North Carolina, and in full force just hours after its landfall at Category-4 strength.

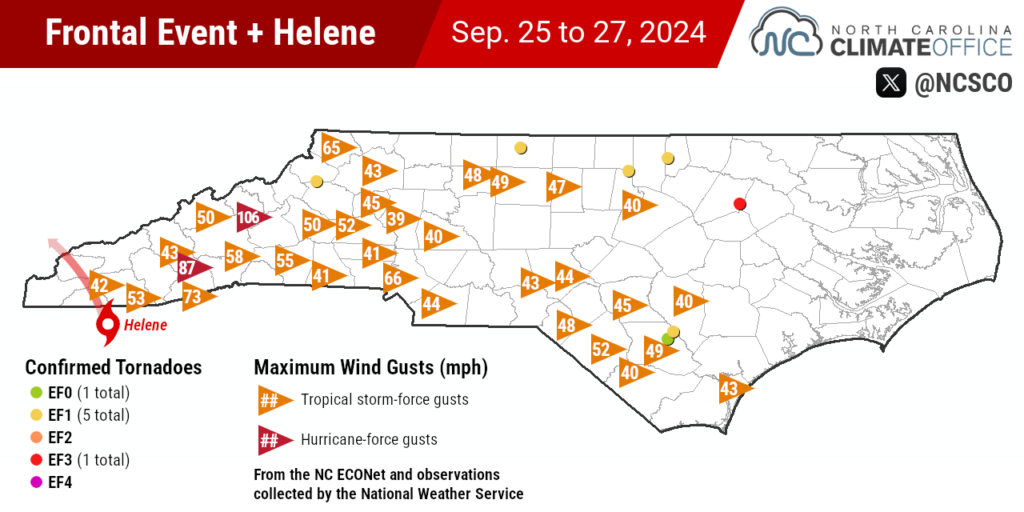

Across the state, the storm whipped up strong winds, with tropical storm-force gusts observed throughout the Mountains, Piedmont, and southern Coastal Plain. The 66 mph gust at the Charlotte Airport was the strongest there since a thunderstorm microburst on August 19, 2019.

On Mount Mitchell, our ECONet station measured a gust of 106 mph at 8:27 am on Friday – the strongest wind observed there since April 2011. Our station on Frying Pan Mountain reported a gust of 87 mph, which is the highest wind it has ever recorded dating back to November 2004.

Those winds produced widespread power outages across western North Carolina. On Friday morning, Duke Energy reported 703,000 customers in North Carolina were without power and 281,000 outages had been restored by then. Since then, those numbers have been slow to decline, with more than half a million outages two days after Helene moved through.

The storm also posed a tornado threat across the state, spawning six confirmed tornadoes on Friday in addition to a rare mountain tornado on Wednesday evening near Blowing Rock – the first in Watauga County since 1998.

The strongest of Friday’s tornadoes was classified at EF3 strength as it crossed Highway 301 in Rocky Mount. Although it was on the ground for only a quarter mile, the tornado destroyed several buildings and caused 15 injuries.

That was the third EF3 tornado in the Rocky Mount area within the past 15 months, joining the July 2023 tornado north of the city and an EF3 spawned by Tropical Storm Debby in Wilson County last month.

The state Department of Public Safety reported that more than 200 people have been rescued from flood waters, but there have been hundreds more calls for rescue and more than 1,000 requests for welfare checks.

That means the death toll is likely to climb as hard-hit areas are finally accessed in the coming days. As of Sunday afternoon, the state had officially confirmed 11 fatalities, but local numbers were already surpassing that figure, including 30 fatalities so far in Buncombe County according to the sheriff.

Sadly, our state’s long-running benchmark for deaths during a tropical event – approximately 80 during the mountain region’s July 1916 flood – could be in jeopardy from this storm that has already broken plenty of other records.

The New Flood of Record

The high terrain of western North Carolina has seen its share of heavy rain and flooding over the years. While tropical systems in that region aren’t as common as along our coastline, those events can become super soakers due to the easily exacerbated precipitation potential when moist air rises up the mountain slopes.

Most recently, Tropical Storm Fred – which was also preceded by slow-moving thunderstorms that saturated soils and streams – produced deadly flooding across Haywood County in August 2021.

But Helene exceeded the coverage and calamity, along with the heaviest rainfall totals, from that event. During Fred, the National Weather Service issued one Flash Flood Emergency – used only rarely during life-threatening and catastrophic water rises – along the Pigeon River. By comparison, portions of 21 counties in North Carolina had those Emergency warnings issued during Helene.

Many in the Mountains also remember the floods and landslides in September 2004, which had been the wettest month ever recorded for many western sites thanks to the tropical trio of Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne.

But the totals from September 2024 will be even greater in some areas, making this the new wettest month on record at sites including Asheville, Sparta, and North Wilkesboro. And that’s not just a figurative high-water mark; the French Broad River in Fletcher crested ten feet higher than its previous peak after Frances in 2004.

Perhaps the only local event in the same ballpark as this one for the southern Mountains is the flood of July 1916, when a remnant tropical storm caused rivers to swell and inundate Asheville and other mountain towns. For more than a century, that event has loomed large as the area’s flood of record.

But that title now belongs to Helene instead, and for good reason. The scale of the impacts was broader and the mountain landscape much more developed now compared to 108 years ago. Because of that, the damage is certain to exceed the inflation-adjusted $641 million from the 1916 storm, likely by an order of magnitude. For reference, Florence caused an estimated $17 billion in damage in the state.

At the few river gauges in the region that observed both Helene and the 1916 storm, the crests since Helene have broken those long-standing records. The French Broad River and Swannanoa River – which collided at high speeds and high volumes in 1916 to overtake Biltmore Village – both saw new record crests during and after Helene.

The French Broad River in Asheville rose 1.5 feet above its previous highest crest, and downstream at Blantyre, the river surpassed its 1916 crest and was still rising when the gauge stopped reporting on Friday afternoon.

The Swannanoa River at Biltmore crested at 26.1 feet, more than five feet above its 1916 maximum and slightly above the apparent 26-foot crest in April 1791, making this effectively the worst flood along the river since North Carolina became a state.

An Historic Storm for the State

By definition, the most extreme events have few comparisons, but it’s hard not to see elements of other notable storms in Helene and its antecedent rainfall.

Just two weeks earlier, a heavy rain event not directly associated with a named tropical system – in that case, Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight – also brought precipitation totals in excess of 20 inches across parts of southeastern North Carolina.

The widespread flooding washing over – and washing out – towns and roadways after Helene was uncomfortably similar to the scenes in eastern North Carolina following Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and Hurricane Florence in 2018. And once again, the major city in the region – Wilmington then, Asheville now – had its interstate connections severed by the flooding.

In addition to those similar impacts, one way of comparing events on opposite ends of the state is using rainfall return intervals, which frame a specific amount over a certain duration as the likelihood of occurring in any given year, such a 1-in-100 year event, with a 1% chance of occurring.

While imperfect due to its lack of recent updates, the most comprehensive return frequency data comes from NOAA’s Atlas 14 product. That showed totals from Hurricane Floyd in 1999 and Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight earlier this summer as roughly 1-in-500 year events, with the totals in excess of 30 inches during Florence classified as worse than 1-in-1000 year events.

Last Friday’s daily rainfall total of 11.89 inches in Celo equals the 1-in-500 year total per Atlas 14. In Asheville, the three-day total of almost 14 inches goes well beyond the 1-in-1000 year total for a 72-hour period, which Atlas 14 cites as 11.4 inches. Likewise, the 24.41 inches over three days at Mount Mitchell is off the charts compared to the noted 1-in-1000 year amount of 16.5 inches.

Yet another event of this magnitude within the state offers even more evidence that our climate is changing, and in extreme ways. The rapid intensification of Helene over the Gulf, the amount of moisture available in its surrounding environment, and its manifestation as locally heavy – and in some cases, historically unheard of – rainfall amounts are all known side effects of a warmer atmosphere.

While we can’t say for sure how many more storms like this we’ll face in the future, it’s a near certainty that we won’t see another Helene in the Atlantic, as that name is a safe bet for retirement by the World Meteorological Organization due to its devastation along the Florida coastline and in the North Carolina Mountains.

In a historic coincidence, a previous iteration of Helene was one of our state’s biggest weather what-ifs. The 1958 storm by that name approached our coast at Category-4 strength, only to turn away at the last moment, sparing areas like Wilmington a direct hit just four years after Hazel.

This year, we’ve seen what a different Category-4 Helene did to coastal areas, battering the Big Bend of Florida with a 15-foot storm surge. But 66 years to the day after the first Helene gave us a close call in North Carolina, there was no avoiding the incredible impacts of this modern-day monster storm with the same name.

A note from our director and state climatologist, Dr. Kathie Dello:

The destruction from Hurricane Helene in western North Carolina has been distressing to watch — much more so for those who are waiting to hear from family and friends in the region. As a public service center for the state, our office wants to share not only the story of the storm, but also how to assist in the recovery.

The best way to support cleanup and recovery efforts is through the North Carolina Disaster Relief Fund, which is accepting donations that go directly to nonprofits working in impacted communities. As of October 7, several organizations are seeking volunteers to help in affected areas. If you’re inclined to help in person, make sure you’ve submitted an application and/or been given an assignment before arriving in areas still cleaning up from the storm.

Discussion about this post