Coming off a soaking September, October offered a decidedly drier pattern, along with mostly warm temperatures. That has made for an unconventional start to fall across the state.

Dry Weather and Drought Return

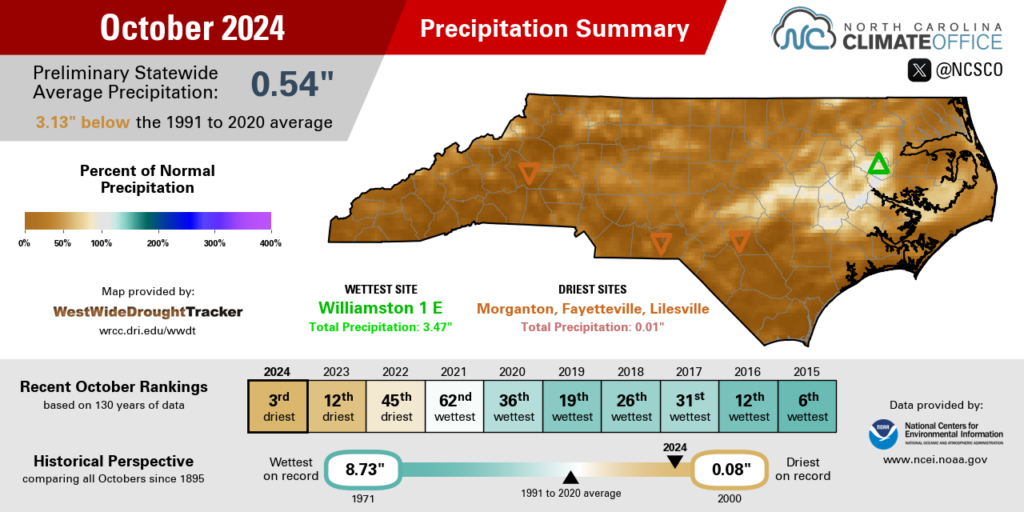

Fresh off the flooding from Hurricane Helene in late September, our weather took a much drier turn in October. The National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), now back online after the hurricane’s heavy impact in Asheville, reports a preliminary statewide average precipitation of only 0.54 inches last month, which ranks as our 3rd-driest October since 1895.

Our only drier Octobers at a state level happened in 2000, with 0.08 inches, and in 1953, with 0.51 inches. This was an even drier month than last October, which had an average of 1.19 inches and saw a steady expansion of drought across the western half of the state.

Thanks to the prevailing high pressure pattern overhead for much of the month, there were few opportunities for rain-making weather systems to move through, and the ones that did generally had limited moisture in tow.

The most significant rain – and a good chunk of the monthly totals in many areas – came on the first day of the month as a low pressure system shifted offshore. That yielded daily totals of up to 3.15 inches in Williamston and 2.20 inches at our ECONet station in Jockeys Ridge State Park.

After that, cold frontal passages on October 5 and 14 brought only light rainfall generally totaling less than half an inch in northern and western areas. Another front passing through on the final weekend of the month brought a bit more widespread rain, including locally higher totals of nearly an inch in Salisbury, but most areas tallied a quarter-inch or less from that system.

Even relatively wet areas were still drier than normal last month. The 3.47 inches in Williamston was almost an inch shy of its 4.29-inch normal October rainfall, and with 2.16 inches, Tarboro had just 64% of its normal monthly precipitation.

At least 20 observing sites across the state finished the month with less than a tenth of an inch of rain in total. That included Morganton, which had just 0.01 inches, and North Wilkesboro, which had 0.07 inches. Raleigh didn’t fare much better, with just 0.11 inches. At all three sites, it was the 2nd-driest October on record, while the Fayetteville Airport had only 0.01 inches all month and its record driest October dating back to 1910.

With so few rain chances all month, some impressive strings of dry days stacked up. Until the rain on October 27, New Bern was dry for the first 26 days of the month, which was tied for the 6th-longest rain-free streak on record there. And through the end of the month, Fayetteville has gone 30 days in a row without measurable rainfall, which is the most consecutive days without measurable rainfall there since December 1988.

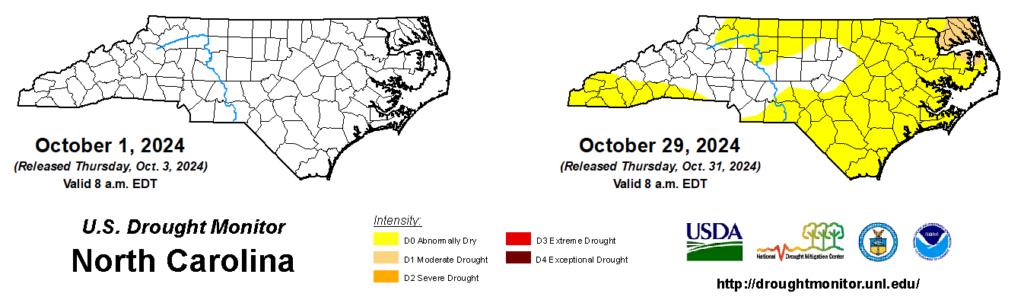

Despite the bone dry weather, drought and its impacts have been slow to return across the state, and that’s largely a testament to how wet we were in September. That lingering moisture has helped keep most streamflow conditions near normal even a month after Helene’s heavy rains rolled through.

Only in the far northeastern corner of the state – which got a head start on drying out thanks to lower rainfall totals from Helene and our other September storms – have groundwater levels recently fallen below normal, in line with the current Moderate Drought (D1) designation in that region.

Warm Weather Bookends the Month

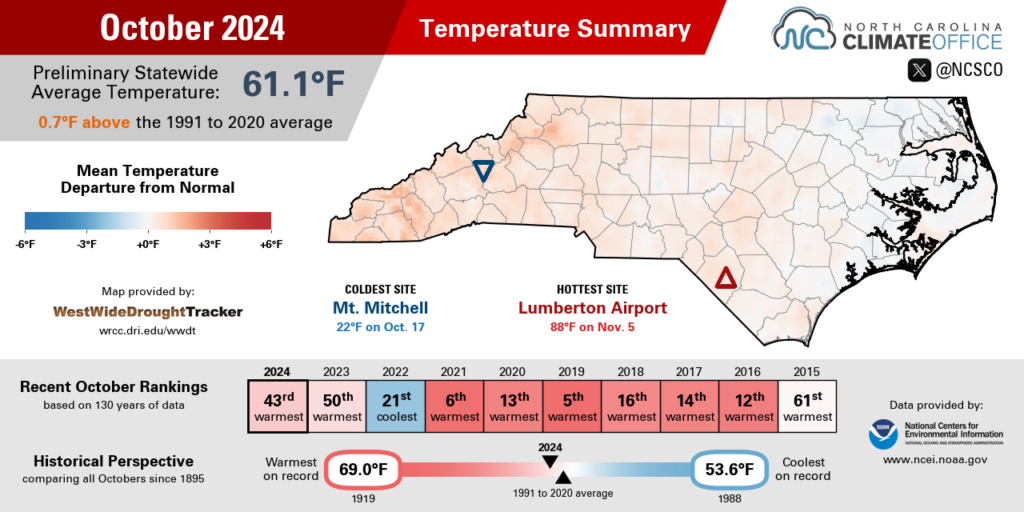

One cool spell was outdone by a warm start and end to the month, making for overall above-normal temperatures in October. NCEI notes a preliminary statewide average temperature of 61.1°F and our 43rd-warmest October out of the past 130 years.

Among local weather stations, it was the 6th-warmest October at W. Kerr Scott Reservoir since 1965, the 9th-warmest in Hickory since 1949, and the 15th-warmest October on record in Asheville dating back 133 years.

The first week of the month featured high temperatures in the 80s across much of the state, including a string of four consecutive days with highs hitting 86°F in Murphy. The last time that happened in October there was in 2019. In Charlotte, temperatures climbed as high as 87°F on October 7, which is more typical of late August than early October.

By the middle of the month, one of the mostly dry cold frontal passages ushered in a much cooler Canadian air mass, which limited our high temperatures to the upper-50s or low-60s. The morning of October 18 also offered the coldest air of the season so far, including sub-freezing temperatures in the Mountains and frosty mid-30s in rural areas across the state.

But that chill was short-lived, as warm weather returned in the final two weeks of the month. That included another run of 80-degree days, including a new daily record high of 85°F on October 26 in Wilmington.

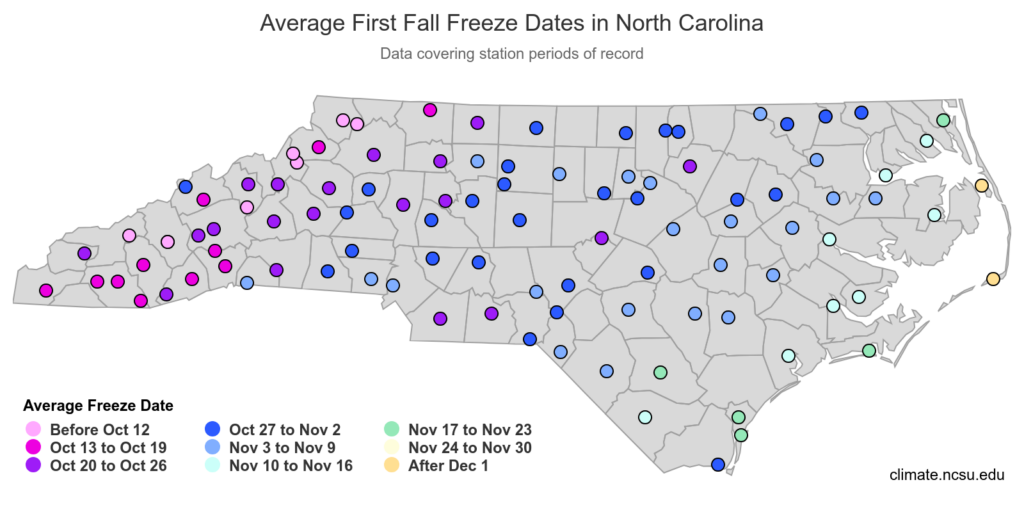

One consequence of that late-month warmth was a delay in the first fall freeze for much of the state. The Piedmont typically sees their first freeze during the final week of October or the first few days of November, but that sort of cold air has been absent lately, and current outlooks strongly favor above-normal temperatures through next week.

That could push the first freeze to record late dates in some western sites. Yadkinville’s latest first freeze on record happened on November 11 in 2017, and Danbury’s latest first freeze was on November 18, 2020, compared to an average date of October 20.

An Unusual Fall Progression

Those recent temperatures more typical of summer than winter aren’t the only strange feature of this fall. The sudden swing from our extremely wet September – with a double dose of heavy rain from Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight and Hurricane Helene – to a bone dry October also stands out as a unique aspect of this season.

From 7.95 inches of precipitation, on average, in September down to just 0.54 inches in October, that was a 7.41-inch change from one month to the next. That’s the sixth-greatest month-to-month decrease in our precipitation since 1895.

Most similar historical events included one or more tropical systems in one month, followed by below-normal rainfall in the following month. That setup explains the common timing: each of the top-ten greatest monthly precipitation decreases happened in the late summer or early fall, when tropical events are most likely but we’re transitioning to a climatologically drier time of year.

| Rank | First Month | First Month Avg. Precip. | Second Month | Second Month Avg. Precip. | Monthly Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sep. 1924 | 10.96 in. | Oct. 1924 | 1.10 in. | -9.86 in. |

| 2 | Sep. 1928 | 11.50 in. | Oct. 1928 | 2.38 in. | -9.12 in. |

| 3 | Sep. 1999 | 13.22 in. | Oct. 1999 | 4.77 in. | -8.45 in. |

| 4 | Aug. 1940 | 9.64 in. | Sep. 1940 | 1.61 in. | -8.03 in. |

| 5 | Sep. 1979 | 10.04 in. | Oct. 1979 | 2.20 in. | -7.84 in. |

| 6 | Sep. 2024 | 7.95 in. | Oct. 2024 | 0.54 in. | -7.41 in. |

| 7 | Aug. 1908 | 10.12 in. | Sep. 1908 | 2.76 in. | -7.36 in. |

| 8 | Sep. 1945 | 9.29 in. | Oct. 1945 | 2.29 in. | -7.00 in. |

| 9 | Aug. 1986 | 8.45 in. | Sep. 1986 | 1.68 in. | -6.77 in. |

| 10 | Sep. 2000 | 6.36 in. | Oct. 2000 | 0.08 in. | -6.28 in. |

Those changes are also evident locally. As NIDIS notes, Asheville followed its wettest month on record in September, in which it totaled 17.90 inches, with just 0.03 inches of rain in its 4th-driest October on record, which was the largest precipitation difference between consecutive months there.

Coming off the record flooding from Helene, the dry October made for an interesting juxtaposition of extremes. With ample debris left behind by the storm, the North Carolina Forest Service is now cautioning about wildfire danger from open burning, especially on dry and windy days when burns can easily spread out of control.

Another obvious contrast between our wet September and dry October can be seen at Lake James. The Bridgewater Hydro Station at the dam was damaged by flooding from Helene and has been out of service since the storm, leaving the lake several feet above its target levels. All the while, the Bridgewater site recorded only 0.01 inches of rain in October.

Perhaps the most noticeable impact of these extremes has been on the fall leaf color – or lack thereof. On his Fall Color Guy page, Appalachian State biology professor Dr. Howard Neufeld noted in mid-October that it was shaping up to be the worst fall for color in the past 20 years or so, and given our wild weather, it’s easy to understand why.

First, hurricane-force wind gusts from Helene blew away many leaves and toppled plenty of trees, especially in high-elevation areas like the slopes of Grandfather Mountain that are the first areas to begin showing signs of fall color.

While October featured plenty of sunny days — which encourages photosynthesis that allows sugars within the leaves produce more red pigments — it also had very few cold nights that are important because they cause green chlorophyll to degrade and the movement of water throughout the trees to slow down, allowing those pigment-producing sugars to build up in the leaves.

The dry weather hasn’t helped either, as some trees have dropped their leaves to conserve moisture before the color change reached its peak. Condition monitoring reports from CoCoRaHS observers in late October noted that leaves were “falling in large numbers” across Madison County, hickory trees in Durham were already shedding most of their leaves, and colors were muted in Hoke County.

As for how this frenzied fall might finish, current outlooks show that freeze-free warmth continuing through mid-month, along with increased chances of above-normal precipitation in a potential reversal of our recent dry spell.

Beyond that, the end of the month is looking warm but dry again in a La Niña-like pattern. For more on what a potential La Niña could mean for our weather this winter, stay tuned to the Climate Blog next week as we release our annual winter outlook on Wednesday, November 13.

Discussion about this post