The Richtersveld Desert Botanical Garden, a first of its kind in South Africa, opened its doors in August. It aims to be a living bank of the endangered and threatened plant species in the region. (All photos by Ashraf Hendricks)

The new botanical garden in Sendelingsdrif is a living bank of South Africa’s rich succulents indigenous to the Richtersveld.

Many succulents are endangered — on the verge of extinction — because of poaching, mining, climate change, and overgrazing. This garden is a beacon of hope amid the rapid decline of these plants.

The Richtersveld Desert Botanical Garden, which opened in August this year, is the country’s first botanical garden in the desert biome.

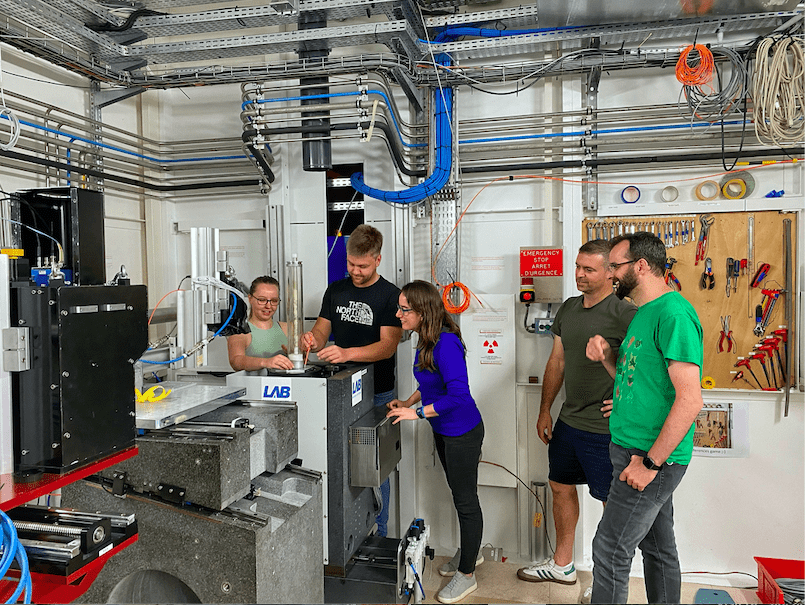

Located in the Ai-Ais Richtersveld Transfrontier Park along the border between South Africa and Namibia, the garden is a partnership between the South African National Parks (SANParks) and the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI).

The garden has been in the works for several years. In 2014 Sendelingsdrif, a small border town, almost became a ghost town when some nearby mines closed down. SANParks staff aimed to give the town a facelift, said Pieter van Wyk, nursery and botanical curator at the botanical garden.

Van Wyk, a self-taught botanist, was assessing plant populations in the region when he realised that many species were going extinct.

“I quickly realised we’re sitting with a serious problem in the Richtersveld — and that was before poaching. When poaching came, it just escalated,” said Van Wyk. In 2021, there were over 400 species that had the potential of going extinct without intervention, he said.

Van Wyk said the aim of the garden is to create a living bank of these plant species currently under threat. “We already have so many species that are alive because of this facility, which otherwise would’ve been gone,” he said.

The botanical garden includes a conophytum house, which hosts hundreds of the tiny succulents, and many which are red-listed because of demand on the black market.

“Poaching has become so extreme. If these species go extinct in the wild, at least we have a backup plan to reintroduce them,” said Van Wyk.

Despite being a desert region, the garden is rich in unique flora with thousands of endemic species found in this biome. Some of the plants are single habitat species. Some have likely been wiped out in the wild in recent times because of human activity.

The garden is open to the public and includes facilities that hold plants saved from poaching, plants saved from mining sites, and a nursery that sells indigenous plants. There is also a Nama kraal, an education centre for the local community.

Van Wyk said that when the poaching crisis struck in 2019, they were quickly flooded with poached material.

From 2019 to date, SANBI has received over a million plants confiscated by law enforcement. But this number only represents about a quarter of plants taken from the wild that are intercepted by law enforcement, said SANBI spokesperson Nontsikelelo Mpulo.

These plants remain with the police until legal proceedings are concluded, “after which they will be transferred to state ownership through agencies like CapeNature or the Northern Cape Department of Agriculture, Environmental Affairs, Rural Development, and Land Reform (DAERL),” said Mpulo.

The poaching crisis has since improved, which SANBI attributes to collaborative efforts between provinces, and “harsher sentencing” especially in the Northern Cape. Last year about 200,000 plants were confiscated, and so far this year only about 30,000 plants have been confiscated.

Mpulo added that SANBI’s focus is on “developing a conservation collection and ensuring that botanical gardens across South Africa and globally can house these unique specimens, preserving them for future generations”.

Eventually, the hope is to reintroduce some of these plants into their natural habitat in the Richtersveld. “Some of the species are key species in the ecosystem,” said Van Wyk.

But there are some places where it might not actually be possible because habitats have been destroyed, such as at mining sites. “We need to protect this … It is part of our natural heritage,” he said.

This article was first published by GroundUp.

Discussion about this post