Turner Adams in a drug den. All photos: Brenton Geach (exclusive copyright)

It was in 2003, while photographing the devastating impacts of tik (crystal meth or methamphetamine) in Cape Town’s poor communities, that I first met Turner Adams.

With an entire life etched into his skin – each tattoo telling a story of survival, pain or, ultimately, resilience – Adams, who died on 29 October, was a man not easily forgotten.

Shafiek Zeeman, Turner Adams’s brother, walks past the coffin with his daughter Asma at the service in Lavender Hill. Long-time friend, Mark Nicholson, on the right.

His family, like so many others, had been forcibly relocated from District Six to the neglected apartment blocks of Lavender Hill, a desolate expanse where apartheid discarded entire communities. It was a place that shaped Adams as much as the ink on his body, although he was always adamant he never wanted to be remembered for his past, or the hardships he had endured.

Adams spent nearly half of his 60 years in and out of prison. Wardens of Pollsmoor Prison knew him as a regular. When I visited him, his mother refused to join me, worn out from decades of prison visits and shedding tears for a son she could never quite save.

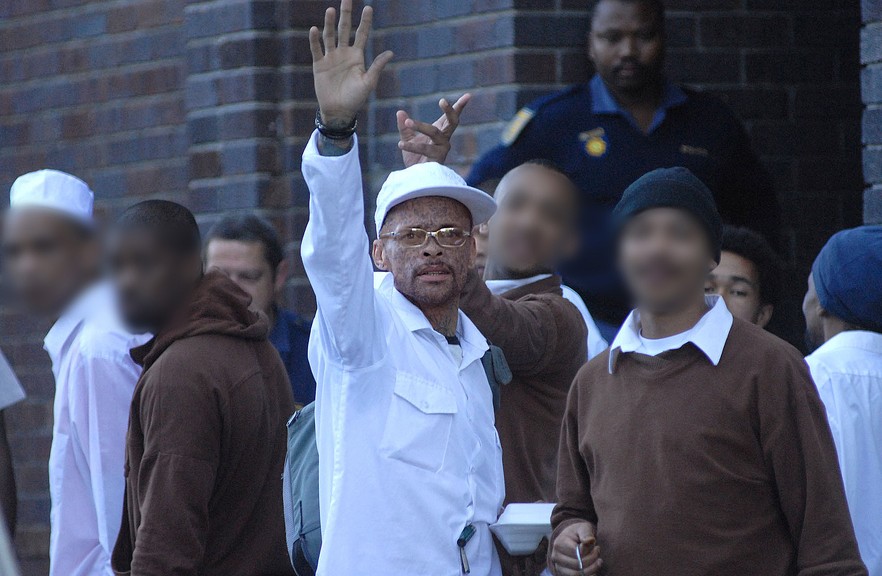

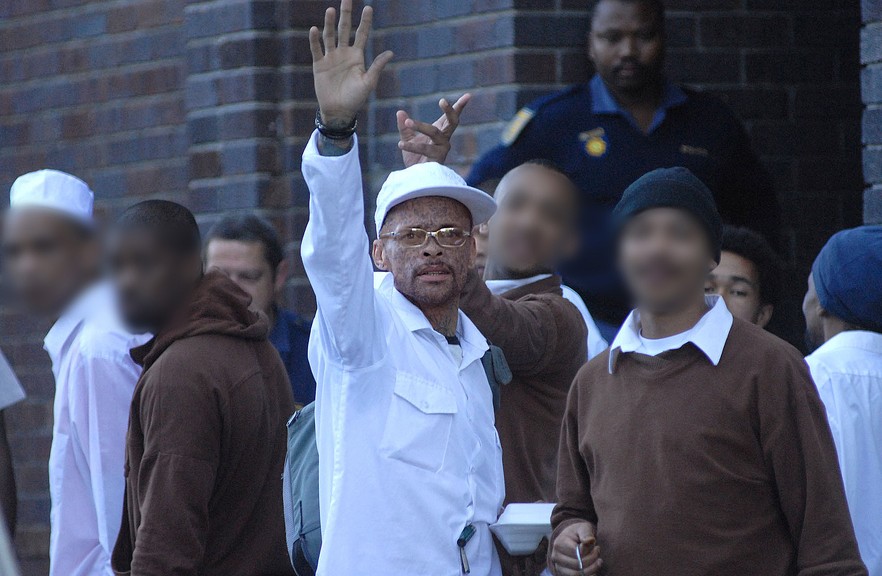

Adams leaving Wynberg magistrates court for Pollsmoor in 2006.

But Adams was more than a high-ranking member of the 28s gang member; he was a storyteller, a philosopher, a man who could talk passionately about everything from world politics to jazz. I could sit with him for hours, transfixed by his tales of life inside and outside of prison.

Although he bore the marks of a gangster, Adams’s dreams stretched beyond Lavender Hill’s unforgiving streets. He often spoke of wanting to be remembered not for his gang ties, but for making a positive difference. He recognised clearly the profound depths of need in the community in which he lived.

Adams and his mother. Adams was very protective over his mother. He had “I die for Mama “ tattooed on his chest

Our images were noticed by local media and filmmakers, and Adams eventually landed a role in Four Corners, a 2013 South African film about a teenage boy whose promising future as a chess player is threatened when he decides to join a local gang. Notably, at Adams’s funeral last week, none of the people who used him in their projects were to be seen.

It was a harsh reminder of how quickly real lives are left behind once stories are told.

Yet, Adams’s dream of giving back to the young people of Lavender Hill did take root. Film producer Janette de Villiers connected with the United Kingdom-based organisation In Place of War, which resulted in the opening of the Rise Above Development (RAD) youth centre five years later.

The Battle field where Mark Nicholson fed 100’s of children daily during the Covid pandemic.

The centre was built on the notorious “Battle Field” in Blode Street, where gang violence had long reigned. Adams was thrilled to see a space where young people might find purpose outside of the gangs and drugs that had defined his own life. The first of five containers for the youth centre arrived in 2022, and today it is home to a music studio, computer lab, library, sports facilities and a community garden, with plans to add a cafe, outdoor theatre and dance studio.

Two other significant Lavender Hill community leaders and good friends of Adams, Mark Nicholson, who fed hundreds of children on the “Battle Field” during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Ralph Bowers, founder of Guardians of the National Treasure, which feeds underprivileged children and families in Lavender Hill, also joined the RAD project.

The first of the five containers which were used for the Youth center.

Adams may not have been actively involved, but he took pride in knowing that something good was emerging from his life story, something meaningful for Lavender Hill’s next generation.

Years of hard drug use had however ravaged Adams’s body, weakening him until he finally succumbed to tuberculosis. He died in hospital, a quiet end to a tumultuous life.

The old adage is that you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, and in Adams’s case, his tattooed body told more than one story.

Adams and his two-month-old baby boy.

© 2024 GroundUp and Brenton Geach. Exclusive copyright. This article is NOT licensed under GroundUp’s usual terms. For permission to republish, please email info@groundup.org.za. If permission is granted, unless otherwise stated, the full text and all photos must be republished as is.

Discussion about this post