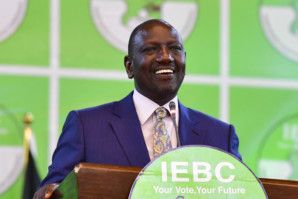

Nairobi: President-elect William Ruto is one of Kenya’s wealthiest men but has long portrayed himself as “hustler-in-chief” – the champion of the poor and downtrodden.

Defying corruption allegations going back years, the ambitious 55-year-old clawed his way to the centre of power by playing on his religious faith and humble beginnings selling chickens by the roadside.

His duel against former prime minister Raila Odinga in the August 9 elections was something that he painted in simple terms.

It was, he said, a battle between ordinary “hustlers” struggling to put food on the table and the elite Kenyatta and Odinga “dynasties” that had dominated Kenyan politics for decades.

“We want everyone to feel the wealth of this country. Not just a few at the top,” Ruto had said as he criss-crossed the country promoting his “bottom-up” economic plan.

The shadowy rags-to-riches businessman had effectively run as a challenger after a very public and acrimonious falling out with outgoing president Uhuru Kenyatta, who backed Odinga for the top job.

Despite a race dominated by mudslinging, Ruto on Monday struck a conciliatory tone after his win, vowing to work with “all leaders” after the outcome split the election commission and sparked fears of violence.

“There is no room for vengeance,” Ruto said, adding: “I am acutely aware that our country is at a stage where we need all hands on deck.”

‘Effective strategist’

Ruto had served as deputy president under Kenyatta since 2013, supporting him in two elections with a promise that he would have the backing of his boss in this year’s vote.

It was a political marriage of convenience forged in the aftermath of deadly post-poll violence in 2007-2008 that largely pitted the Kikuyu – Kenyatta’s tribe – against the Kalenjin, Ruto’s ethnic group.

Both men were hauled before the International Criminal Court (ICC), accused of stoking the ethnic unrest.

The cases were eventually dropped, with the prosecution complaining of a relentless campaign of witness intimidation.

But Ruto was left out in the cold after Kenyatta shook hands with longtime foe Odinga in a dramatic switch of political allegiance in 2018.

He bounced back with a campaign that was directed as much at Kenyatta as his rival at the ballot box, blaming the government for Kenya’s economic woes and even accusing the president of threatening him and his family.

“Ruto is seen by many people to be one of the most effective strategists in Kenyan politics,” Nic Cheeseman, a political scientist at the University of Birmingham in Britain, said before the poll.

‘Perfect storm’

Clad in the bright yellow of his United Democratic Alliance, whose symbol is the humble wheelbarrow, Ruto sought to reach out to those suffering most from the Covid-induced cost of living crisis that has been aggravated by the war in Ukraine.

Ruto “picked the perfect storm,” Kenyan political analyst Nerima Wako-Ojiwa said before the election.

Observers attribute Ruto’s aggressiveness to the fact he has had to struggle to get everything he has achieved in life from his lowly start in Kenya’s Rift Valley, the Kalenjin heartland.

“I sold chicken at a railway crossing near my home as a child… I paid (school) fees for my siblings,” he once said.

“God has been kind to me and through hard work and determination, I have something.”

His fortune is now said to run into many millions of dollars, with interests spanning hotels, real estate and insurance as well as a vast chicken farm.

A teetotal father of six who describes himself as a born-again Christian, Ruto seldom lets a speech go by without thanking or praising God or reciting from the Bible.

He first got a foot on the political ladder – and detractors claim, access to funds – in 1992. After completing studies in botany, he headed the YK’92 youth movement tasked with drumming up support for the autocratic then-president Daniel arap Moi, also a Kalenjin.

In 1997, when he tried to launch his parliamentary career by contesting a seat on his home turf of Eldoret North, Moi told him he was a disrespectful son of a pauper.

Undeterred, Ruto went on to clinch the seat, which he retained in subsequent elections.

His detractors say he siphoned money from the YK’92 project and used it to go into business, and allegations of corruption and land grabs still hang over him.

But he has long dismissed such claims, once telling local media: “I can account for every coin that I have.”

Discussion about this post