The NOAA-funded Climate Adaptation Partnership team, Carolinas Collaborative on Climate, Health and Equity (C3HE), held a workshop that allowed team members to meet in person, share their research and view it through a new multidisciplinary lens.

On November 8, the Carolinas Collaborative on Climate, Health and Equity (C3HE) held a workshop for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers at the Museum of Life and Science in Durham, North Carolina. The day challenged students to share data and methods, identify gaps in their research, and identify opportunities to approach their climate-health hazards research from a multidisciplinary perspective.

The C3HE team is made up of approximately 30 researchers, community members, and students spanning multiple academic, research, and science education institutions. Team members perform research with the goal of helping communities across North and South Carolina understand and predict their climate risk — how hazards such as flooding or heat could affect them.

On the morning of the workshop, around 25 participants began to trickle into a large windowed room for the session. The students snacked on coffee and bagels while making light conversation with each other, many of whom had only previously interacted through Zoom. Some had come down the road from NC State University or UNC-Chapel Hill, while others had completed an approximately seven hour drive from Georgia State University.

That morning, researcher Tara Wu from Penn State University said she looked forward to connecting with more people researching climate science, and forming shared definitions and understandings on such a complex topic.

“Understanding where research is headed is super important,” Wu said. “I like to think of myself as a ‘bridger’ — I’m very interested in research, but I’m also interested in creating actionable science. So, taking what research is saying and bringing it onto the ground.”

Wu had just recently moved to the Raleigh-Durham area from Asheville following its devastation from Hurricane Helene. She reached out to the C3HE leadership, who invited her to this meeting.

“I’m just really excited to be here,” Wu said. “This is incredibly important work. It definitely hits home right now.”

The next generation of climate solutions

Once the room was properly filled with laughs from an ice-breaker challenge, the workshop kicked off with opening remarks from team leaders like C3HE co-director and North Carolina State Climatologist Kathie Dello, C3HE co-director and epidemiologist Jennifer Runkle, NC State senior program manager Kalyn Rosenberg, UNC assistant professor and principal investigator Antonia Sebastian, and C3HE community engagement lead and principal investigator Max Cawley.

The graduate students and postdocs then gave “flash talks:” in no more than five minutes, each was tasked to share who they were, what they researched, what questions their research aims to answer, and where they work within the risk framework — whether that’s quantifying hazards, studying exposure, measuring risk, or identifying adaptation strategies. Presenters also shared their research methods, which communities and stakeholders they may work with, how their research can be applied, and their ultimate research goals.

Research ranged from studying algal blooms to helping the National Weather Service create clearer alerts for heat advisories and excessive heat warnings, or examining how extreme temperatures may impact Black birthing outcomes.

“Seeing in one short go what the breadth and the depth are of the students who are working in the climate risk and resilience space is very inspiring,” Sebastian said. “These students are the next generation of people who are going to push forward not only the science around climate risk, but also the solutions around climate risk.”

For students like Hunter Quintal, a third-year Ph.D. student at UNC-Chapel Hill, the talks highlighted possibilities for collaboration across disciplines.

“I don’t often think about the applications of my work in the greater context of all of this work from all of these different perspectives unless we’re all in the room together,” Quintal said. “So, it’s a very helpful opportunity for thinking about the broader impacts of the work that we do.”

Once students were acquainted with each other’s work, workshop leaders had them split into groups with others within their disciplines, with groups ranging from natural sciences to humanities. They were encouraged to discuss what parts of the risk framework their discipline focuses on, what data is necessary for their work, what kinds of data they do or do not have access to, and other outstanding questions they might have.

Conversations varied drastically from group to group. Students with a natural science focus spent time discussing traditional and new approaches to analyzing climate hazards, and how “hazard” should even be defined — should it be from an impacts perspective or a physical modeling perspective? For example, if there is precipitation, does it become a hazard event when it impacts roads, or when there are two inches of rain?

Other groups delved into conversations on research fatigue, and how to ensure communities in need of help don’t feel abandoned by researchers after data collection. Some discussed making sure collected data is trustworthy and reflects the experiences of those familiar with an area. The humanities group explored positionality and what qualifies as bias.

“We’ve been talking about what centers us,” said Haven Cashwell, a postdoctoral research scholar with the North Carolina State Climate Office (SCO) who participated in the humanities discussion. “With our work, we really focus on people. We have people within this room who are doing statistical modeling, quantifying hazards, but all that information essentially ties to people in some way or another. So, I’m thinking about how I can be a better communicator, be a better researcher, and emphasize the people-centered focus of this work.”

Such thought-provoking conversations called for a brief break for students.

“So far, so good,” Cashwell said.

Avoiding oversimplification

After some more time within their discipline-based groups, students broke for lunch and toured the museum’s new climate exhibit, and they visited with the bears, red wolves, and lemurs. Once they reconvened, it was time for students to break out of their comfort zones by working in new interdisciplinary groups.

Each group was given a large paper, markers, and sticky notes, and instructed to create a map showcasing the drivers of climate risk in the Carolinas. Through charts and illustrations, students brainstormed social and economic forces that affect who is exposed to hazards and how hazards can affect well-being.

Many groups discussed what ties people to places, such as their family history or social network. One group explored what hazards can be overlooked in an area, stating that if hazards are only thought of in the context of disasters, it risks missing “creeping threats,” such as saltwater intrusion. Groups discussed how historical and modern oppression have contributed to risks, such as landfills being predominantly placed in Black communities.

Most groups commented on the overlapping and cyclical nature of social, economic, and driving forces of climate risk; aspects like age can impact mobility and ability to evacuate, which could in turn impact future finances, mobility, and evacuation ability. This complexity led students at several tables to debate how to best visualize the information without oversimplifying it.

For third-year NC State graduate student Lily Raye, the interdisciplinary discussions were her favorite part of the day.

“It was really inspiring and motivating to continue conversations I’ve had in the past, but also start new conversations with my colleagues,” Raye said. “I got a lot of good ideas about how to use datasets I already have, and work with gaps with other people’s data sets. That was really cool, to see where I could fill those gaps with other resources in the room.”

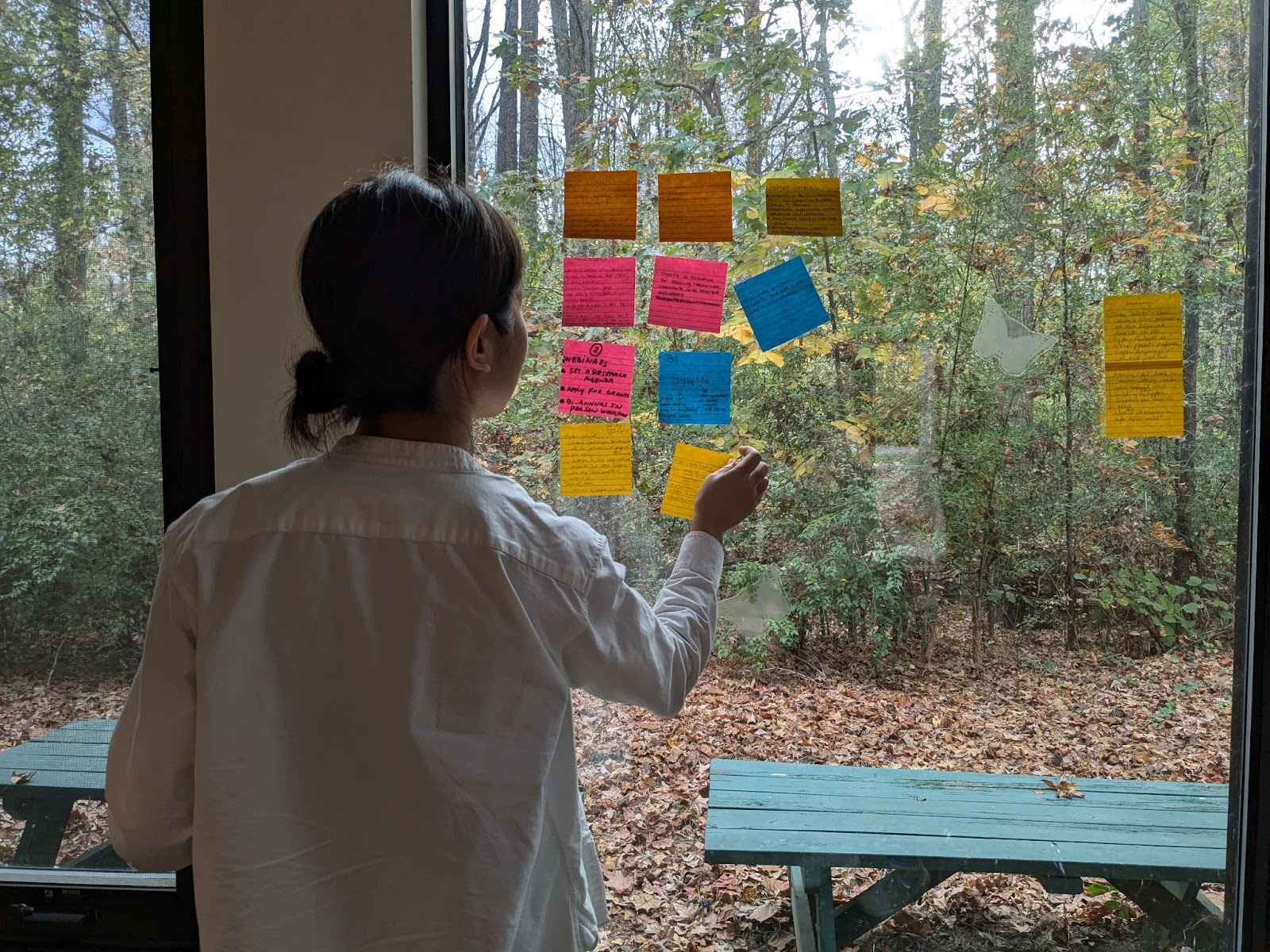

Groups presented their maps to one another before beginning the day’s final activity. Individually, students now reflected and wrote on sticky notes opportunities they saw for future research, how to stay connected, and build team momentum.

After about 10 minutes, the tall windows of the room were filled with neon pink, yellow, and blue sticky notes containing suggestions for more webinars, group chats, and mentorship sessions.

The approximately eight-hour day concluded with a powerful reminder from team leaders to carry out research in the service of others, and in service of the future.

For Alyssa Griffin, a second-year graduate student at NC State who conducts research with SCO, it had been a day of complicated and nuanced discussions, but joined together by a drive to serve.

“Defining what ‘hazard’ and ‘vulnerability’ is is extremely complex, more complex than I realized,” Griffin said. “We have a lot of awesome people who come from all different backgrounds, thinking about how we can best quantify and qualify these things so that the research that we’re putting forth for all of our partners and communities is the most accurate and the most digestible, so people can make really good decisions for themselves.”

As students packed up and left the building, many remarked on feeling hopeful, motivated and inspired.

“I think this was a good grounding point for all of us to come together and realize that while the future may be uncertain, what we’re doing right now is just so amazing,” Raye said. “There’s so many possibilities that can continue even through the uncertainty.”

C3HE is funded by NOAA’s Climate Adaptation Partnerships (CAP) Program, formerly known as the Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments (RISA) Program.

Discussion about this post