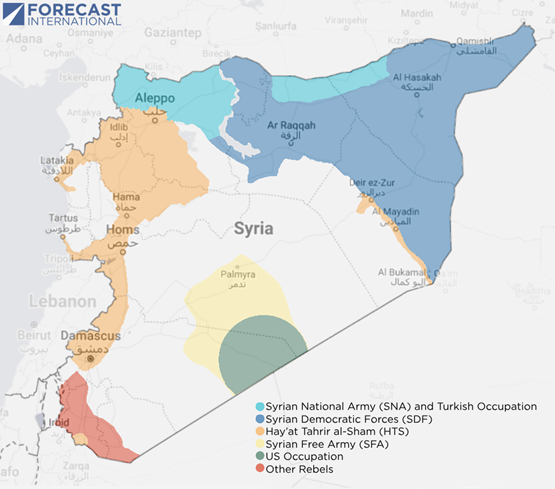

Over a decade after protests sprung up against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in 2011, rebel forces, long on the back foot of the conflict, have accomplished the unthinkable and toppled the regime. Following a lightning offensive beginning in late November, a coalition of anti-government rebels seized the major city of Aleppo and subsequently overran government positions as far as the capital of Damascus. The developments ended over a half-century of Assad family rule, leaving the Middle Eastern nation at an unprecedented crossroads, with its future hanging in the balance. The conflict had been largely stagnant following a 2020 ceasefire deal brokered between Turkey and Russia, with major offensives ceasing and borders between the remaining factions solidifying. Anti-government rebels were largely confined to the northwestern province of Idlib, with most of the country’s west in the hands of the regime. The eastern third of the country has been held by the U.S.-backed, Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Turkey and affiliated proxies likewise held territory in the country’s north, frequently fighting the Kurdish-led SDF. This balance held relatively stable for years, underscored by the belief in a seemingly inevitable regime victory over beleaguered rebel forces.

Illusions were shattered on Nov. 27, when the Islamist rebel group and U.S.-designated terrorist organization Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), supported by other groups including the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), launched a major offensive out of Idlib into the Aleppo region. After three days of minimal fighting, the rebels controlled most of Syria’s second-largest city. On Dec. 5, the city of Hama, the site of an infamous 1982 regime massacre, was liberated. By Dec. 8, the capital city of Damascus was overrun by a new offensive including U.S.-backed rebels from the southeast. Faced with a string of sudden defeats, President Bashar al-Assad fled the country for Russia, marking a crashing end to his 14-year rule.

With a Whimper, Not a Bang

The rapid fall of the Assad regime revealed numerous vulnerabilities in what was thought to be a durable regime. Assad’s fall can be attributed to a wide range of military, political and economic factors.

Syria’s regime, while fielding a sizable force, was never a military juggernaut. Instead, Assad was reliant on deals with local militias and groups, as well as significant aid from outside actors. Nations such as Russia and Iran, as well as affiliated groups like Lebanon’s Hezbollah propped up regime forces extensively throughout the conflict. Recently, Russia’s priority has been its larger conflict in Ukraine, and fewer resources have been available for its Middle Eastern ally. Likewise, Israel’s dismantling of Hezbollah in Lebanon and air strikes on Iranian assets in Syria have greatly reduced the capabilities of Damascus’ local allies. In October, Hezbollah began to divert troops away from Syria to reinforce its own positions in Southern Lebanon amidst an ongoing Israeli invasion, opening the door to renewed rebel offensives.

The economic situation in Syria has also become particularly dire in recent years. The UN assessed that 16.7 million Syrians currently require humanitarian aid, the most since the outbreak of the civil war. An April 2024 bulletin estimated a 120% inflation rate, putting Syria in the top five worst countries for inflation this year. Skyrocketing inflation has destroyed consumer purchasing power and eroded regime support. It similarly muted the effects of a last-ditch 50 percent soldier pay increase issued by Assad before his fall. Soldier bonuses were also raised last December to bolster cratering army morale, though a collapsing currency value rendered the gesture ineffective.

In contrast to the regime’s defense, the rebel offensive showed speed, professionalism, and determination, reflecting coordination between different groups on the ground. The push startled government forces, leading to a rapid collapse of unenthusiastic soldiers. Momentum from the advance into Aleppo quickly snowballed, as other opposition groups, including the SDF and U.S.-backed Syrian Free Army (SFA) began their own attacks on crumbling regime positions. The offensive spearheaded by HTS and the SNA brought to bear a renewed rebel zeal, revealing the hollowness of the regime military, demoralized and unsupported by outside allies.

What Comes Next

The regime’s collapse has left several armed groups in control of a divided Syria. The common unifying factor, opposition to Assad, is no longer in play, opening the door to further conflict over the country’s future. While the possibility of nationwide elections and stable governance led by HTS still exists, the prevalence of armed groups and outside influence in Syria offers sizable obstacles to an immediate peaceful resolution of the country’s divisions.

Turkey is the major foreign beneficiary of the regime’s collapse, rewarding Ankara’s yearslong strategy of sponsoring rebel groups. The recent success of Turkish proxies will embolden Ankara to further seek the erosion of Kurdish sovereignty and the establishment of a compliant, friendly government. Turkey’s relationship with HTS is, however, less robust than with the SNA, sharing the U.S. designation of the group as a terrorist organization. While HTS is likely to come to terms with Turkey for support, the extent of Turkish influence in the country and the degree of involvement of Turkish proxies in the new government may be a focal point for future conflict among rebel groups.

The downfall of Russia’s primary proxy in the region is an undeniable loss for Moscow, rolling back years of investment in the Syrian regime. Assad’s collapse will force the evacuation of Russian forces across the country, including from the strategic Tartus naval base and Khmeimim air base, both situated on the Mediterranean coast. The former is Russia’s only Mediterranean seaport and a key refueling and supply route for Russia’s extensive presence in West Africa.

Israel and the United States may celebrate Assad’s collapse but greet the uncertainty of an HTS-led Syria with caution. Both states will prioritize the containment of extremist elements and the prevention of renewed Russian and Iranian influence. Israel, for its part, has deployed troops to a buffer zone on the border with its occupied Golan Heights and conducted air strikes to destroy ex-regime military assets including chemical weapons and aircraft. Incoming President Donald Trump seems unlikely to prioritize Syria in his foreign policy, and as such U.S. support for the SDF and other opposition groups may wane in the new Syria, forcing the Kurdish-led coalition to reassess its strategic positions.

* * *

The Syrian opposition’s stunning success revealed a paper tiger regime, far weaker than most believed, opening the door to expansive new possibilities. Simmering economic issues and a crisis of morale and discipline within the Syrian Army enabled massive rebel gains over a short period. Despite the regime’s collapse, the country still faces widespread challenges to rebuilding, stemming from significant poverty and humanitarian crises, as well as the prevalence of armed groups and conflicting foreign interests. As HTS begins forming a new Syrian government, doubts persist about the group’s capacity to unify the country peacefully, with the potential for existing factional and ethno-regional divisions, spurred on by foreign influence, to outweigh unification efforts.

Tom Freebairn is a weapons analyst with Military Periscope covering naval affairs and maritime systems. He pursued an undergraduate degree in International Relations and Modern History, followed by a master’s in Middle East, Caucasus, and Central Asia Security Studies from the University of St. Andrews. His master’s thesis focused on the relationship between oil and separatist politics in Northern Iraq. Tom’s interests include the politics of energy, ethnic separatism, the evolution of naval warfare, and classical history.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/09/b6/09b60007-939d-45c0-85a2-c95dc6f9d447/oldestanimals_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post