China will need to install around 10,000 gigawatts (GW) of wind and solar capacity to reach carbon neutrality by 2060, according to new Chinese government-endorsed research.

This huge energy transition – with the technologies currently standing at 1,408GW – can make a “decisive contribution” to the country’s climate efforts and bring big economic rewards, the China Energy Transformation Outlook 2024 (CETO24) shows.

The report was produced by our research team at the Energy Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Macroeconomic Research – a “national high-end thinktank” of China’s top planner the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC).

The outlook looks at two pathways to meeting China’s “dual-carbon” climate goals and its wider aims for economic and social development.

In the first pathway, a challenging geopolitical environment constrains international cooperation.

The second assumes international climate cooperation continues despite broader geopolitical tensions.

We find that, under both scenarios, China’s energy system can achieve net-zero carbon emissions before 2060, paving the way to make Chinese society as a whole carbon neutral before 2060.

However, the outlook shows that meeting these policy goals will not be possible unless China improves its energy efficiency, sustains its electrification efforts and develops a power system built around “intelligent” grids that are predominantly supplied with electricity from solar and wind.

(Carbon Brief interviewed the report’s lead authors at the COP29 climate talks in Baku last November.)

Trends governing China’s energy transition

China’s rapid economic growth over the past decades has driven a massive increase in industrial production, particularly energy-intensive industries such as steel and cement, requiring vast amounts of energy.

To meet the high demand for energy, the country has built up a coal-based energy sector.

In 2014, Chinese president Xi Jinping introduced the concept of “four revolutions and one cooperation”, which calls for a drastic change in how energy system development is thought about.

The following 13th “five-year plan” (2016-20) – an influential economic planning document – required a shift from maintaining and developing a system based on fossil fuels to creating a system that is “clean, low-carbon, safe and efficient”.

This led to the announcement of China’s “dual-carbon” targets in 2020, which positioned achieving a peak in emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 as integral to China’s economic development in the future.

As part of this, policymakers are working towards a “new type of energy system”, in which low-carbon technologies will simultaneously provide energy security and affordable energy prices, as well as addressing environmental concerns.

In the past few years, however, electricity demand has grown rapidly due to increased production of goods after the Covid-19 pandemic and the impact of heatwaves.

Furthermore, the supply of hydropower has been hampered by the lack of water because of droughts. This has led to a push for new investments in coal power, despite a massive deployment of solar and wind power plants.

The challenge today is related to this transformation’s speed – how China can vigorously accelerate renewable energy deployment to cover growing energy demand and substitute coal power.

Scenarios for carbon neutrality

CETO24 looks at two scenarios for its analysis of China’s energy transformation towards 2060. The first – the baseline carbon-neutral scenario (BCNS) – assumes geopolitics continues to constrain low-carbon cooperation.

The second – the ideal carbon-neutral scenario (ICNS) – assumes climate cooperation avoids geopolitical conflict.

Both scenarios envision that China will reach peak carbon emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060, against a backdrop of the growing urgency of global climate change and increasing complexity and volatility of the international political and economic landscape.

The BCNS assumes that addressing climate change may become a lower priority globally, but that China still meets its “dual-carbon” goals. The ICNS assumes that other countries prioritise accelerating their domestic energy transformation and cooperation on climate change, despite occasional political or economic conflicts.

The outlook models the two scenarios and analyses the transformation of end-use energy consumption in different sectors, such as industry, buildings and transportation.

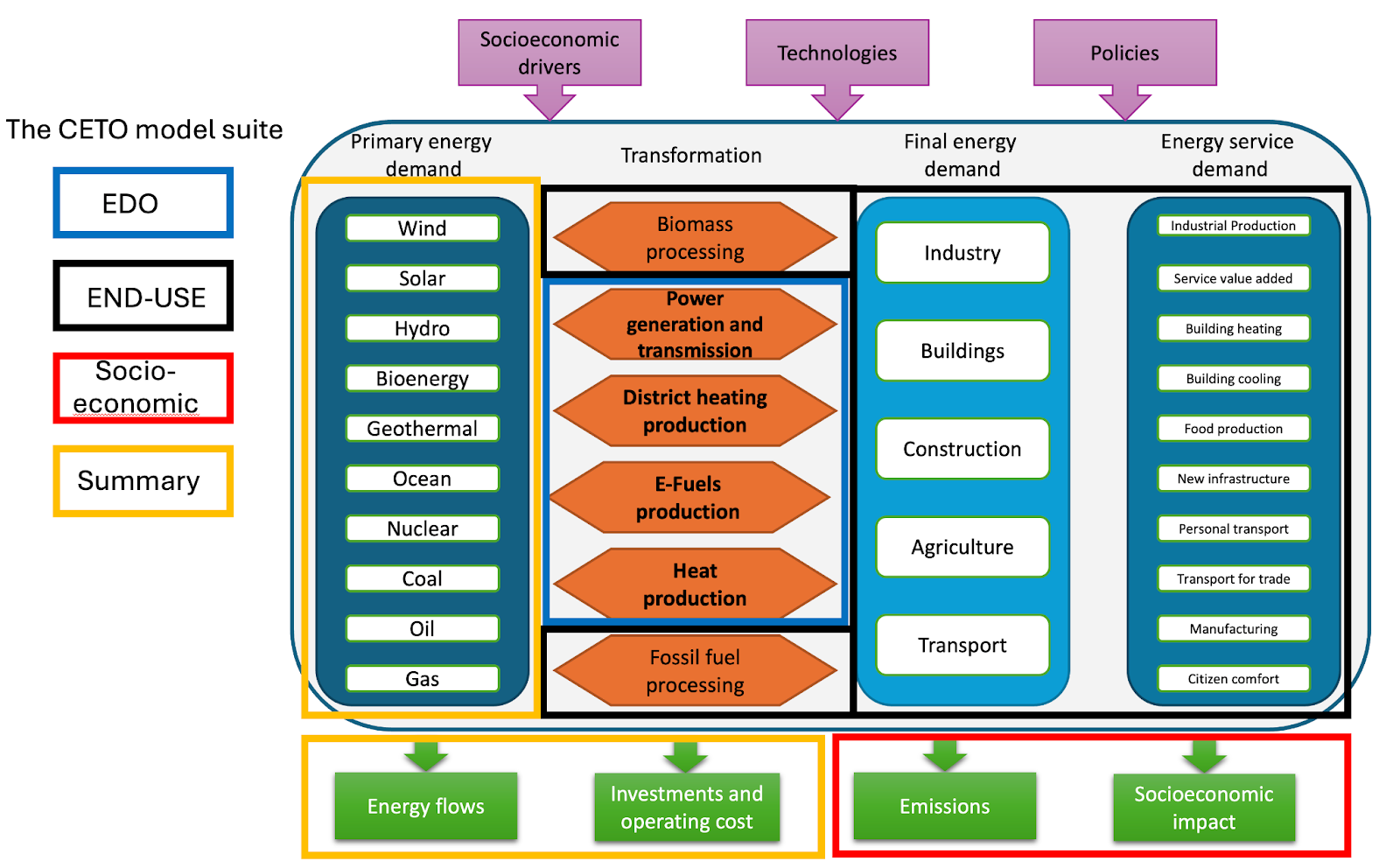

The CETO model suite, used in the outlook, is illustrated in the figure below. For example, the electricity and district heating optimisation model (EDO, blue box), looks at power, heat and “e-fuel” production in great detail with an hourly resolution, in order to capture the fluctuations in variable renewable energy output at provincial level.

EDO looks at the least-cost pathway to reach the dual-carbon goals for the whole power system, including the production, storage and transport of electricity.

On the demand side, the end-use energy demand analysis model (END-USE, black box) allows for different modelling approaches in the different sectors. The model also includes the processing of fossil fuels and biomass.

The EDO and END-USE models are supported by a socioeconomic model (red box), which looks into the macroeconomic impact of the energy transformation and vice-versa.

The results from the models are used in the summary model (yellow box), which shows the primary energy consumption, the energy flows for the whole energy system and the investments and operating costs for the supply sectors, as modelled in the EDO model.

Our strategy for developing the new type of energy system, based on the models shown above, consists of:

- Focusing on efficient use of energy in the end-use sectors, with an emphasis on a shift from fossil fuel consumption to the direct use of electricity (electrification).

- Transforming the power sector to a zero-carbon emission system, mainly based on wind and solar.

- Ensuring that the grid management system – the system of transmission, distribution and storage of electricity – is able to deal with the fluctuations in production and demand. This includes more focus on flexible demand, as well as digital, intelligent control systems to manage system integration, cost-efficient dispatch of supply and demand, as well as energy security in the short- and long-term.

The approach of the model is to promote system-wide optimisation for the two scenarios. This allows for the analysis of the complex interaction between demand, supply, grids and storage, seeking to optimise the whole system, instead of optimising subsystems on their own.

The approach is based on a least-cost modelling of the power system, along with the production and distribution of low-carbon fuels, such as green methanol, green hydrogen, e-fuels and so on.

The demand-side modelling allows for flexible methodologies for the different end-use sectors, with “soft links” to the power and low-carbon fuel optimisation model.

The models are constrained to ensure that China’s dual-carbon goals are met. In other words, the energy system’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions peak before 2030 and reach net-zero before 2060.

Other assumptions built into the models include a moderate economic growth rate and a shift in China’s economic structure to focus more on high-quality products and services instead of heavy industry, which has much higher energy consumption per unit of economic output.

Pathway to achieving ‘dual-carbon’ targets

The analyses for both scenarios in CETO24 confirm that China’s energy system can achieve net-zero carbon emissions before 2060, paving the way to make Chinese society as a whole carbon neutral before 2060.

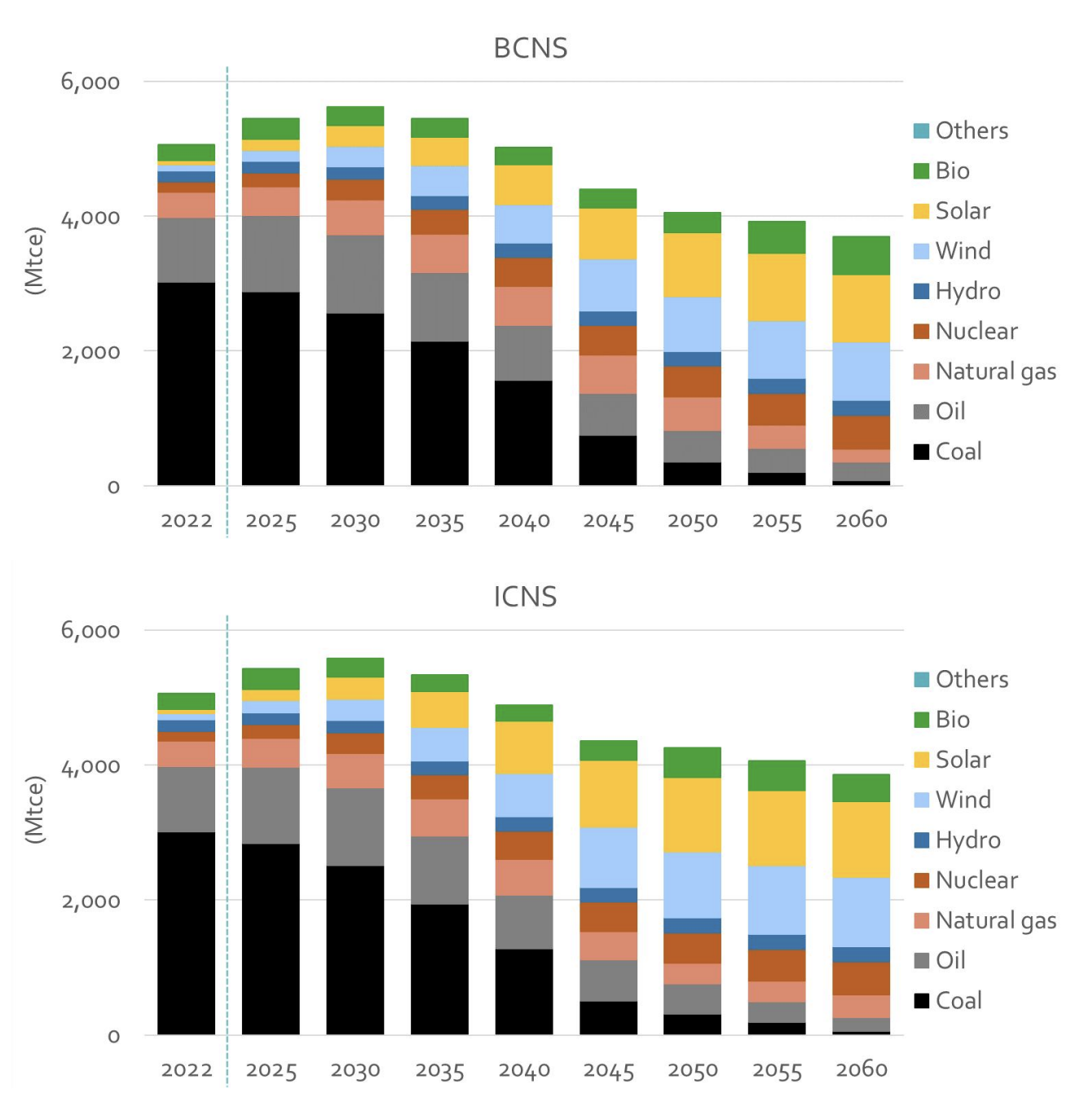

Shown in the figures below, in both scenarios, primary energy consumption peaks before 2035 and declines thereafter, despite the assumption that China’s economy will grow between 3.3 to 3.6 times its 2020 level in the period until 2060.

Both scenarios underscore the importance of energy conservation and efficiency as prerequisites for energy transition.

This is because without effective energy conservation, China’s energy transition would demand significantly greater deployment of clean energy sources, making it difficult to achieve the necessary pace to hit the dual-carbon targets.

Sustained electrification drives carbon neutrality

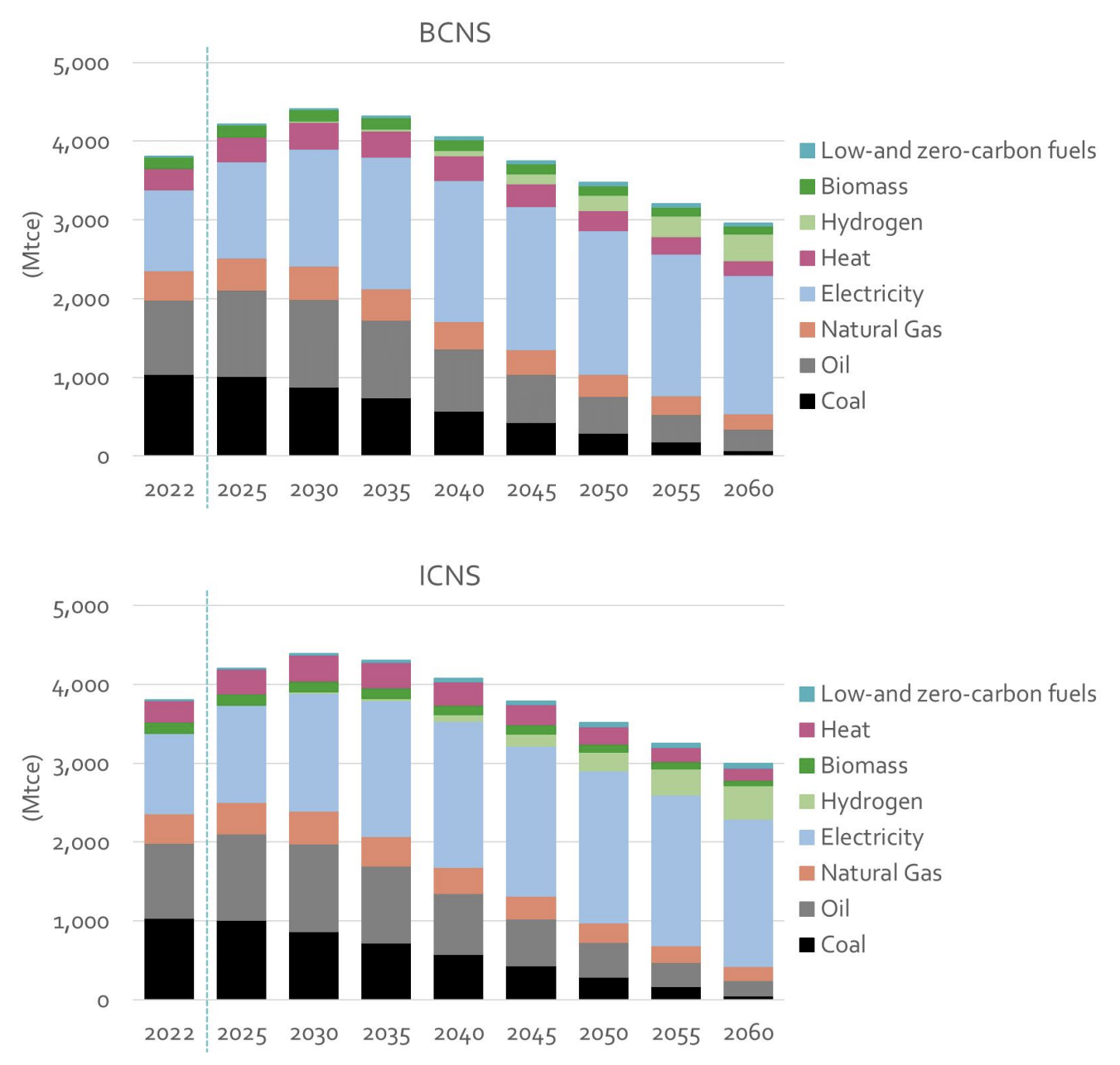

In order to reach carbon neutrality, CETO24 suggests that the use of fossil fuels in the end-use sectors should be substituted by clean electricity as much as possible.

Furthermore, electricity should also be used to produce synthetic fuels or heat supply to satisfy end-use demands for energy.

In 2023, China’s electrification rate was around 28%. The report’s figures, illustrated below, show that electricity (light blue) accounts for as much as 79%-84% of the total end-use energy demand in 2060.

In both scenarios, the transportation sector is expected to experience the fastest growth in electrification, while the building sector achieves the highest overall electrification rate.

Some fossil-fuel-based fuels would still be needed to support certain industries, such as freight transport and aviation, by 2060.

Nevertheless, both scenarios indicate that China’s end-use energy demand would peak before 2035, followed by a gradual decline, with the 2060 value being roughly 30% lower than the peak.

(It is important to note that end-use energy demand is not the same as useful energy services, such as warmer buildings or the movement of vehicles. The replacement of fossil fuels by electricity results in a more efficient use of energy in the end-use sectors, since the losses of energy from burning fossil fuels are removed. Hence, it is possible to reduce final energy consumption even as demand for energy services rises.)

The short-term growth in the end-use energy demand is due to the rapid increase in electricity demand.

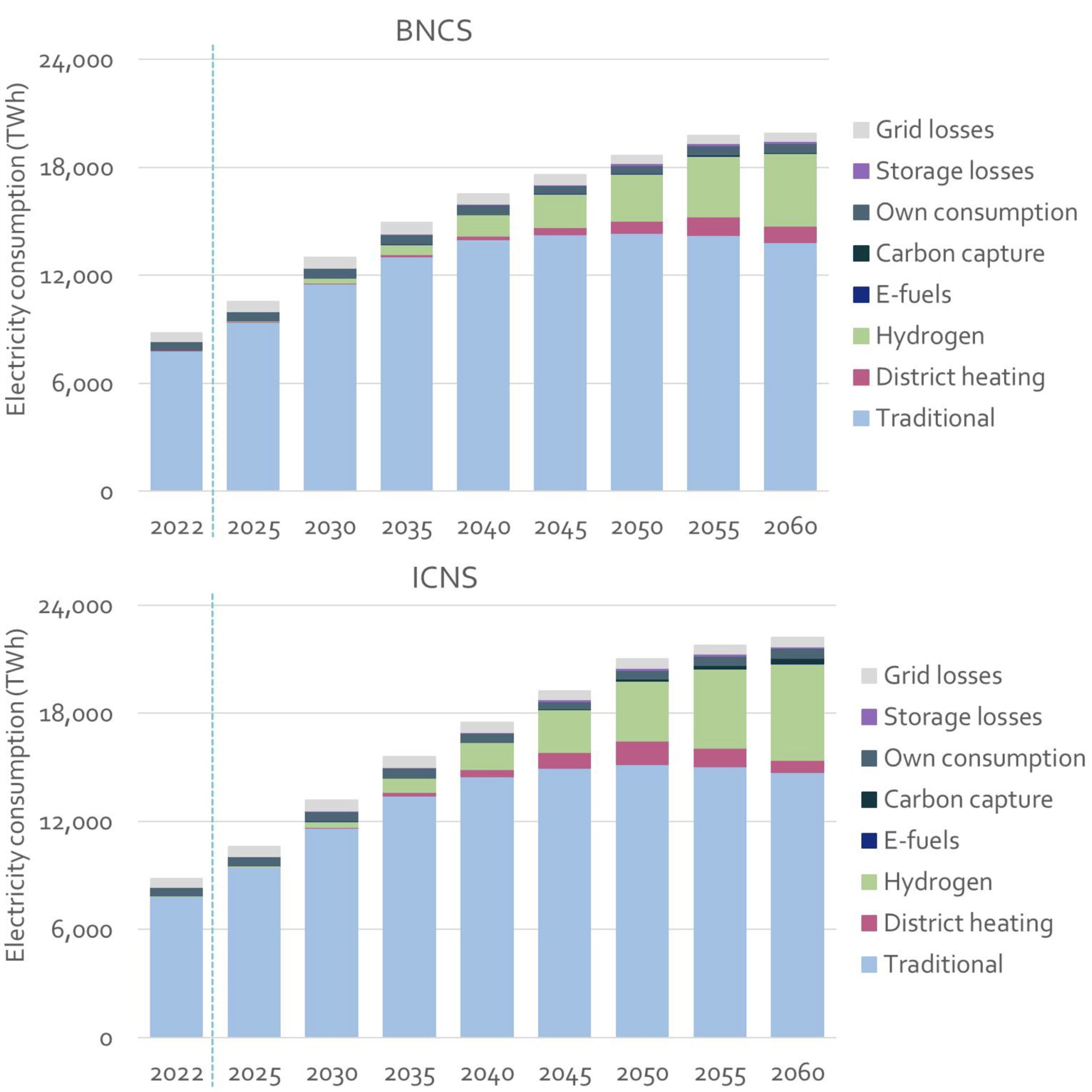

As shown in the graphs below, the share of electricity demand from traditional end-use sectors (blue) – mainly from industry, buildings and transport – would decrease from 89% in 2022 to 68%-72% by 2060.

In contrast, an increasing share of electricity is expected to be used for new types of demand such as for hydrogen production (light green), electric district heating (pink) and synthetic fuel production (dark blue).

Building a power system centred on wind and solar

CETO24 finds that decarbonising the energy supply is a lynchpin of energy transformation – and replacing fossil fuel power with non-fossil sources is the top priority.

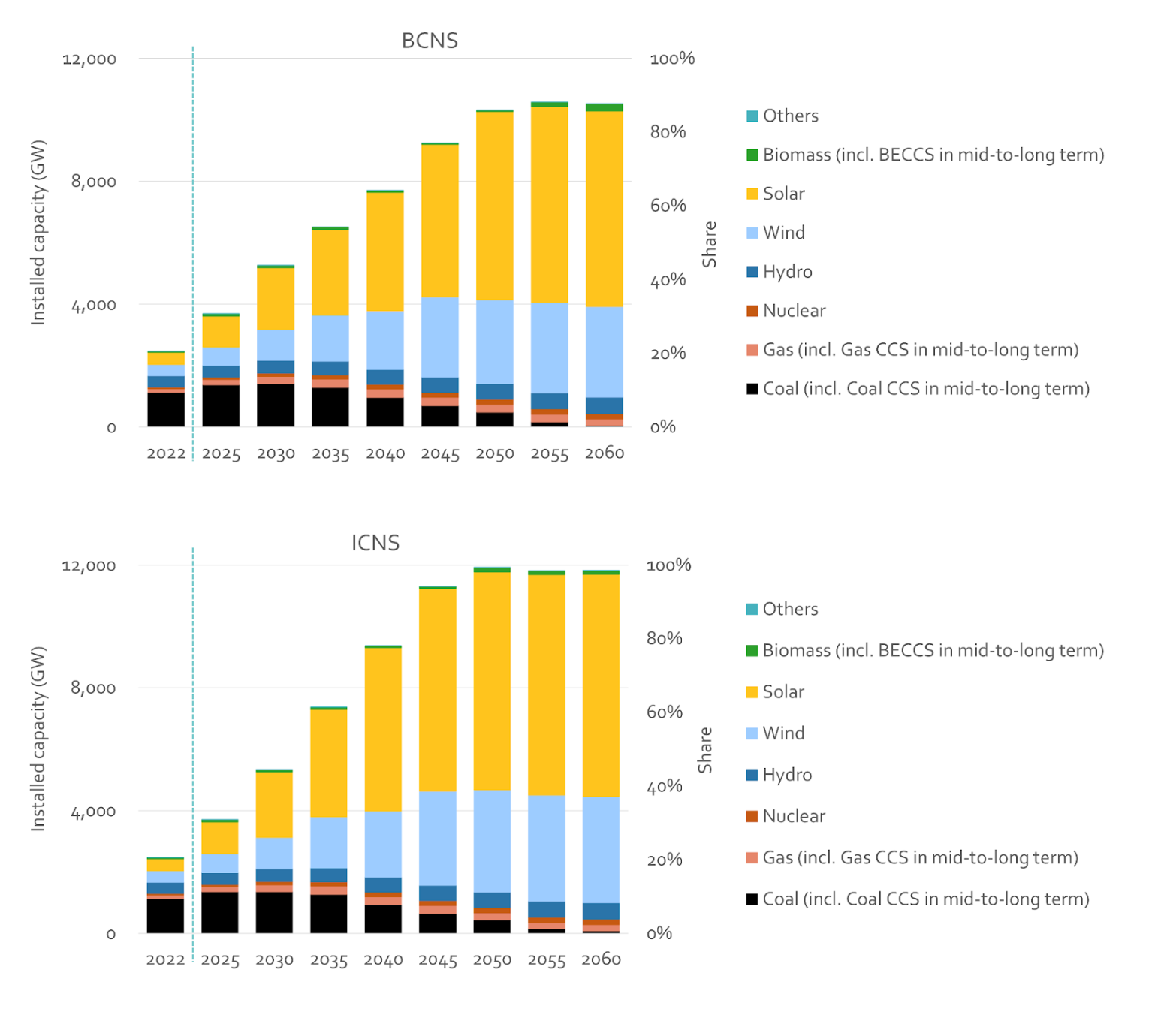

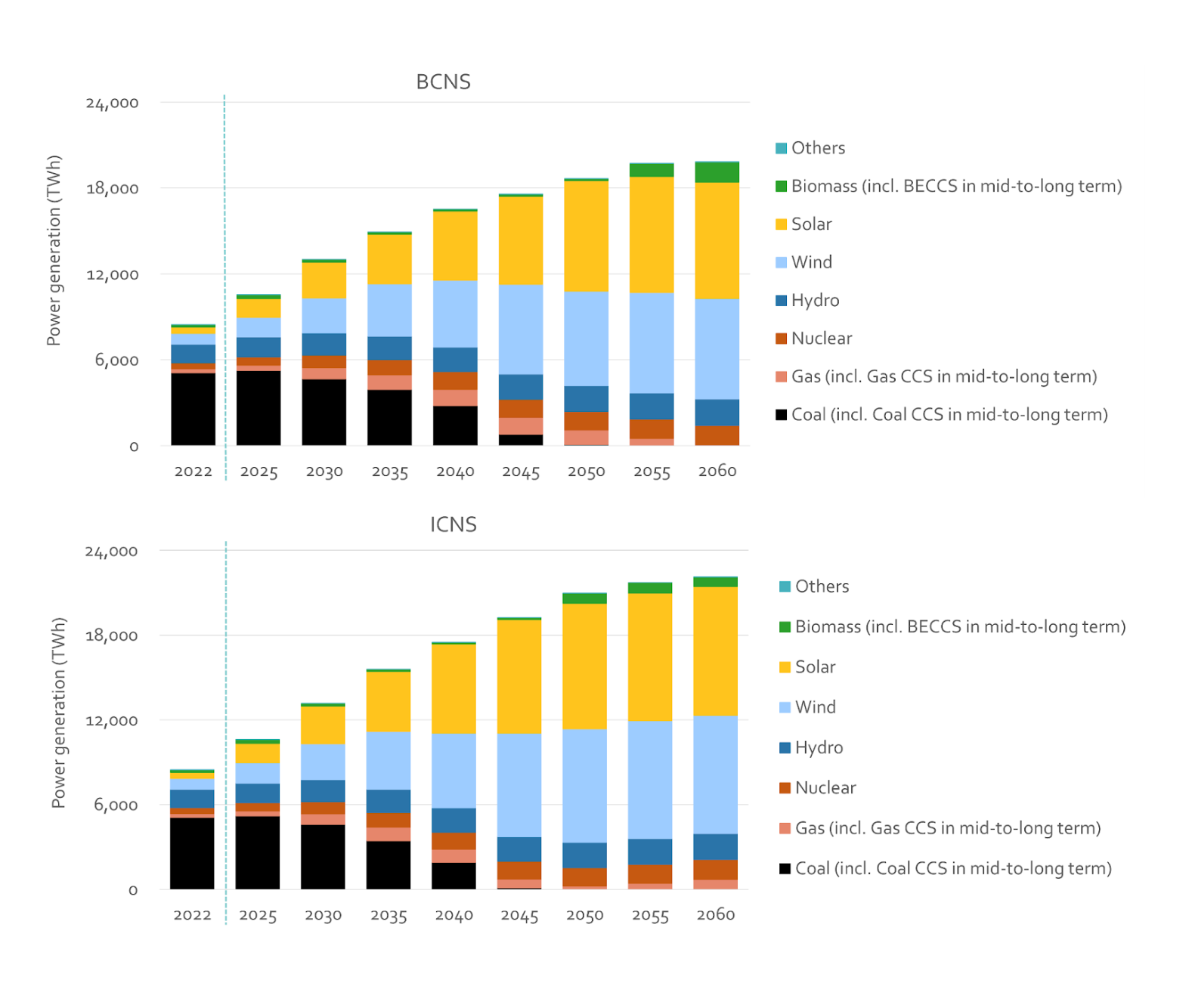

In 2023, non-fossil sources comprised 53.9% of China’s power capacity. In the report’s scenarios, as shown in the figures below, the total installed power generation capacity could reach between 10,530GW and 11,820GW by 2060 – about four times the 2023 level.

The installed capacity of renewable energy sources – including solar (yellow) and wind (blue) – would account for about 96% of the total in 2060.

The installed capacity of nuclear power (dark pink) and pumped storage power (in hydro, dark blue) could reach 180GW and 380GW, respectively. Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) (dark green) would have an installed capacity of more than 130GW.

In addition to dominating installed capacity, wind and solar could account for as much as 94% of China’s electricity generation by 2060, as shown in the figure below.

Energy transformation in China adheres to the principle of “construction new before destruct old” (先立后破). (The principle is also translated as “build before breaking”. See Carbon Brief’s articles from 2021 and 2022 for background.)

As new low-carbon energy capacity grows and power system control capabilities gradually improve, coal power will gradually shift to a regulating and backup power source, with older and less efficient capacity being decommissioned as it reaches the end of its life.

Building an intelligent power grid

The construction of a new power system is a core component of China’s energy transformation.

CETO24 suggests that a coordinated nationwide approach would be the most efficient way to facilitate this. It would integrate all resources – generation, grid, demand, storage and hydrogen – to create a power grid that enables large-scale interconnection as well as lower-level balancing.

This coordinated nationwide approach would involve three key elements.

First, an optimised electricity grid layout, with the completion of the national network of key transmission lines by 2035, enabling west-to-east and north-to-south power transmission, with provinces able to send power to each other. By using digital and intelligent technologies, the grid would be able to adapt flexibly to changes in power supply and demand.

By 2060 in both of CETO24’s scenarios, the total scale of electricity exports from the north-west, north-east and north China regions would increase by 140% to 150% compared to 2022 levels.

Second, this approach would see continuous improvements in the construction of local electricity distribution grids, allowing them to adapt to large-scale inputs of distributed “new energy” sources such as rooftop solar.

As part of this element, China would need to promote the transformation of distribution grids from a unidirectional system into a two-way interactive system. It would also need to focus on providing and promoting local consumption of renewable energy sources for industrial, agricultural, commercial and residential use.

The creation of numerous zero-carbon distribution grid hubs would be needed to provide strong support for the development of more than 5,000 GW of distributed wind and solar energy, which is a feature of CETO24’s modelled pathways.

Third, the multiple energy networks would need to be combined, fully integrating power, heat and transportation systems. This would create a new-type energy network where electricity and hydrogen, in particular, serve as key hubs.

Under both scenarios, the scale of green hydrogen production and use could reach 340-420m tonnes of coal equivalent (Mtce) by 2060. Hydrogen and e-fuel production through electrolysis would become an important means to support grid load balancing – using excess supply to run electrolysers – and to facilitate seasonal grid balancing, with stored hydrogen being used to generate power when needed.

Battery energy storage capacity could reach 240-280GW and the number of electric vehicles could reach 480-540m, with “vehicle-to-grid” interaction capacity reaching 810-900GW, providing real-time responsiveness to the power system.

Innovation and market forces for energy transition

The development of “new productive forces” is a distinctive feature of China’s energy transformation.

Low-carbon, zero-carbon and negative-carbon technologies, equipment and industries, such as electric arc furnaces for steel production, hydrogen-based steelmaking furnaces, high-efficiency heat-pump heating systems, among others, offer broad market potential and present significant investment opportunities.

From the perspective of energy equipment demand, the scenarios show that by 2060 China’s installed wind and solar power capacity would reach approximately 10,000GW.

In the scenarios, the annual investment demand for wind and solar power equipment in China would grow from approximately two trillion yuan ($270bn) per year in 2023 to around six trillion yuan ($820bn) per year by 2060, with cumulative investment needs over the next 30 years exceeding 160tn yuan ($22tn).

The energy transformation will also require China to update or retrofit energy-using equipment across various sectors over the next 30 years, including industry, buildings and transportation.

While playing a smaller part than electrification and efficiency, CETO24’s modelling also points to an essential role for technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) and industrial CO2 recycling, if China is to reach carbon neutrality.

In order for these technologies to be deployed at scale on the timelines needed, more and greater research and planning would need to begin now.

If it is to contribute to the dual-carbon goals over the next 30 years, China’s energy system will need to enter an accelerated phase of equipment upgrades and retrofits, with the scale of demand for such improvements continuing to grow, providing a sustained driving force for economic growth.

Strengthening international cooperation on energy transformation would also help China and other countries reduce the manufacturing, service and usage costs of new energy transformation technologies, enabling both China and the world to achieve carbon neutrality sooner and at lower cost.

Last but not least, a complete legal system for energy is likely to be a key requirement for a successful energy transition. China’s new energy law came into force in the beginning of 2025. More reforms in the legal system, carbon pricing, as well as data management would add significant support to energy transition.

Focusing on enabling forces

In summary, CETO24 demonstrates that there are technically feasible solutions for China’s energy transformation. However, it is still a long-term and challenging societal project.

China would need to reach peak carbon emissions by the end of this decade and then cut them to net-zero within 30 years, far more quickly than the trajectories envisaged by developed economies.

In order to be successful, policymakers will need to face the challenges head-on, find solutions and seek clarity amid uncertainty, to ensure that China’s energy transformation stays on track and progresses steadily.

Our research suggests their solutions could aim to address five areas: electrify energy consumption and improve energy efficiency; decarbonise energy supply; enhance interaction between energy supply and demand; industrialise energy technologies; and modernise energy governance.

At the same time, strengthening international cooperation on energy transformation and exploring pathways together with the global community would allow China to both ensure the smooth progression of its own energy transformation and contribute significantly to the global effort.

Sharelines from this story

Discussion about this post