Kenya’s founding father Jomo Kenyatta once wrote that his Kikuyu ethnic group, the country’s largest, governed itself according to “democratic principles”.

But, in a country whose electorate has long voted on ethnic lines and for established political dynasties, it came as a shock to his political heirs when the Kikuyu people in Kenyatta’s home region of Mount Kenya voted overwhelmingly for deputy president, William Ruto, a Kalenjin. Ruto’s party, the UDA, and its allies also swept through all nine governorships of Mount Kenya.

“We underestimated the extent to which our people have been taken hold of by UDA,” said Jeremiah Kioni, secretary-general of Jubilee, the party of outgoing president and Kenyatta’s son, Uhuru, who endorsed veteran opposition leader, Raila Odinga.

Ruto, who cast himself as a “hustler” facing off against political titans, secured victory on a narrow margin this week and Odinga, a Luo who was making his fifth attempt at the presidency, is challenging the election result in the courts.

It is unclear when Ruto will take power but his triumph heralds a move away from ethnic voting and independence-era politicians. Although nationwide Ruto was declared winner by a razor-thin margin of 1.64 per cent of Kenya’s total votes, he bagged a landslide victory in Mount Kenya, Kenyatta’s home territory.

With an average turnout of roughly 67 per cent, slightly above the national average of about 65 per cent, Ruto bagged some 80 per cent of the votes while Odinga had over 18 per cent in the combined nine counties of the Mount Kenya region, according to data from Equal Politics, a platform sourcing official results.

“We certainly are very democratic. We’ve grown up together with Uhuru, but he has denied us, betrayed us, so, all of us voted for Ruto,” said Margaret Njeri Mubuu, a neighbour of the Kenyatta family in the town of Mutomo. She is also the leader of a group of almost three dozen Kikuyu in Mutomo who voted in block for Ruto.

For the first time since the return of multi-party politics in the 1990s, there was no Kikuyu candidate running for Kenya’s presidency. Transcending ethnicities, Ruto delivered a “hustler nation” cross-ethnic message with promises to invest heavily in agriculture, which resonated among farmers in Mount Kenya who are facing higher food and fertiliser prices.

“People no longer vote on an ethnic basis,” said Gabriel Kagombe, who was elected as member of parliament for Mutomo under Ruto’s party, the UDA. “Ruto said that this nonsense of people voting on a tribal basis, and having no other consideration at the ballot other than tribe, must come to an end. He has managed to kill tribalism in this country. It’s the dawn of a new era.”

A growing detachment of the elite from its power base also contributed to Ruto’s victory. While the Kenyattas have become one of Kenya’s richest families, people in Mutomo complain of a lack of both a hospital and a secondary school, of clean water, and land grabbing by the “deep state”.

Uhuru Kenyatta was so confident of his support in the region that he didn’t visit “the people. Ruto took advantage of that and went down to the remotest villages of Mount Kenya and talked to the lowest of the market vendors. He took a strong populist approach and his populism won,” said Peter Kagwanja, who campaigned for Odinga and is head of the Africa Policy Institute, a think-tank in Nairobi.

“The president ignored the region, people were just fed up,” said Justin Muturi, Speaker of Kenya’s National Assembly and spokesperson for the communities of Mount Kenya. “They just felt William Ruto was the better option. People resonated with his down-to-earth approach and economic message and the concerns of the people. They felt that he was closer to them than Uhuru Kenyatta. It has nothing to do with being Kikuyu or not anymore.”

The results in Mount Kenya point to a shift away from ethnic politics, which had in previous polls led to deadly post-election violence. “This time we didn’t care about the tribe. We just voted for a man we believed in, a man who had stood with us through the times and needed our support,” said Cecily Mbarire, the governor-elect of Embu with Ruto’s party, once an ally of Kenyatta.

The same families have dominated the Kenyan political scene since the 1960s when Jomo Kenyatta and Odinga’s father, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, competed for power in the aftermath of independence from Britain.

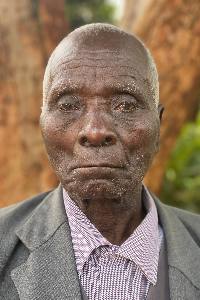

Ruto, a protégé of the late president Daniel arap Moi, delivered his Rift Valley voters to Uhuru Kenyatta in 2013 and 2017 against Raila Odinga, on the understanding that he would succeed the president in 2022. The Kikuyu took that to heart, they said. But Uhuru Kenyatta instead flipped to throw his weight behind his one-time enemy, Raila Odinga. By doing so, he “broke” the Kikuyu principle of keeping one’s word, or kiriiko, said Joel Kumuru, an 87-year-old farmer from Mutomo who voted for Ruto this time.

This was “a betrayal,” said George Keingati, a member of the Kikuyu group in Mutomo. “It doesn’t matter if Ruto is a Kalenjin, he is one of us now, he listens to us.” The switch also confused voters. “This time, he was telling us that Ruto was not good, but the one who was competing against them before, Raila, now he’s good. How? It doesn’t make sense,” said Joseph Kamau, a 27-year-old Kikuyu mechanic from Nyeri.

Odinga has until Monday to make a legal appeal. The court then has two weeks to decide. Kikuyu voters warn that Odinga’s attempt to push for a rerun is unwelcome. “We voted them out now and if they try to come again, we will vote them out again, and in larger numbers, we’ll bring more people,” Mubuu said.

Echoing the losses felt by Odinga and Kenyatta, Gideon Moi, a son of the longstanding former president, lost his seat in the senate. “It is an erosion of this power group,” said Macharia Munene, a Nairobi-based political analyst. “People are turning away from that, saying that they are no longer going to be taken for granted.” For Kagwanja: “Old dynasties are gone, possibly new dynasties will come. Ruto himself is evolving as a dynasty.”

Discussion about this post