Stephanie Garcia was flipping through TV channels when she saw his face. It stopped her cold.

She was sitting with her husband in the living room of their ranch house on a sprawling piece of creek-side property nestled among Texas live oak trees. The color drained from Garcia’s face. A tear ran down her cheek. What’s wrong? her husband asked. They’d been through a lot in their decades together, but he’d never seen her react like this.

It was 2017, and the face on TV belonged to Justin Sneed, a slight man with gaunt cheeks. Garcia recognized him from 20 years earlier as the thieving, unpredictable maintenance man at a run-down Best Budget Inn on the outskirts of Oklahoma City.

On January 7, 1997, Sneed committed the brutal murder of motel owner Barry Van Treese inside Room 102. Back then, Garcia was working as an escort and dancer at the Vegas Club, a strip club that sat kitty-corner to the motel. She worked a club circuit with a group of women who traveled the country together, performing at venues from California to Oklahoma to Florida. When they were working at the Vegas Club, Garcia and her crew stayed at the Best Budget Inn, which was rife with drug dealing and prostitution.

Conditions had begun to change, however, after Van Treese hired 32-year-old Richard Glossip to manage the motel. “Richard was just a square, quiet-type guy, but hardworking,” Garcia recalled. He’d run off the worst of the drug trade and much of the revolving-door prostitution, though he let Garcia and her friends stick around. And he tried to fix the place up where he could. “He made that place better. He cleaned it up. He had places in the rooms painted. He had the ugliest plaid chairs put in,” she said. “And you could go out to your car at night and get something without being terrified.”

Sneed had come to town as part of a roofing crew from Texas, and Glossip brought him on to do some work around the motel in exchange for a place to stay. Garcia did not like Sneed; he was constantly stealing from motel guests in order to feed his growing drug habit. He fancied himself a pimp and tried to take money from Garcia’s friends. “He was slick. I mean, you turn your back on him, in a second he’ll have his hand in your purse,” she said. By the end of 1996, she recalled, Sneed was always high, often shooting methamphetamine. “He was just nasty with it,” she said. “He wouldn’t be able to find a vein, get mad at his needle, and he’d just throw it. … He disgusted me.”

The week before Van Treese’s murder, Garcia said Sneed was behaving particularly erratically. He’d grabbed one of her girlfriends by the throat, pinning her against a motel room wall. Garcia panicked, pulled a knife on Sneed, and told him to let her friend go. He did. She and her crew packed up and hit the road. They didn’t return until after Van Treese’s murder. When she heard what happened, Garcia’s first thought was that Sneed was responsible. “I said it right away,” she recalled.

Photos of Justin Sneed taken by Oklahoma City police in January 1997.

Photo Illustration: Elise Swain/The Intercept and Joseph Rushmore; Photos: Courtesy of the Oklahoma City Police Department

What she didn’t expect was that detectives would quickly decide it was Glossip who’d put Sneed up to the crime. Police — and eventually prosecutors — fixated on a narrative that 19-year-old Sneed was merely a hapless dolt whom Glossip had coerced into carrying out a murder-for-hire plot. The motel operated mostly in cash, and Van Treese only came by periodically to collect the receipts and pay the staff. Once Van Treese was dead, the official story went, Glossip had promised to split whatever cash he had on him with Sneed.

To Garcia, this was nonsense. In her experience, Sneed was the dangerous one, aggressive and conniving. She tried to tell the police about him, but they wouldn’t listen. Instead, she said, they threatened her, telling her to keep her mouth shut about what had been going on around the motel or she would face arrest. Garcia, who’d been to prison before, heard the warning and got out of town.

Still, over the intervening years, she regularly thought about Glossip, Sneed, and the murder at the Best Budget Inn. She figured investigators would eventually realize that their suspicion of Glossip was unfounded. But sitting there in her home that night in 2017, the TV flickering in front of her, Garcia realized that hadn’t happened: Instead, Glossip had been charged with Van Treese’s murder and ended up on death row. He’d come close to execution multiple times.

Garcia has faced a lot of challenges in life. She escaped horrific childhood abuse; joined a carnival where she rode a motorcycle inside a metal cage; wrangled alligators and rattlesnakes at a roadside attraction; battled addiction and years of chronic medical problems. But seeing Sneed’s face, and learning of Glossip’s fate, shook her to the core. If only she’d stood up to the cops and told them what she knew about Sneed and the circumstances preceding Van Treese’s murder, she thought, things might have turned out differently. “That was the whole problem,” she said. “Richard would have never been there if us girls had stayed there and just took their bullshit, let them arrest us if they’re going to, and kept telling the truth.”

After seeing Sneed on TV, Garcia reached out to Don Knight, Glossip’s attorney. As it turned out, she was one of dozens of people who had information relevant to the case but were never interviewed by law enforcement. She hoped that her story would be enough to set the record straight. Instead, on July 1, the state of Oklahoma set a fourth execution date for Glossip.

As Glossip’s lawyers fight yet again to save the life of their client, Garcia can’t shake the feeling that she bears some responsibility for his fate. “It is my fault,” she said. “I’ve really been afraid that I’m going to take this to my grave.”’

Photo: Joseph Rushmore for The Intercept

Things to Clean Up

Since the moment he was arrested in January 1997, Glossip has maintained his innocence for orchestrating the murder of Barry Van Treese. The Intercept was the first national news outlet to dig into his case; an investigation published in July 2015 revealed myriad problems plaguing Glossip’s conviction: a perfunctory and biased police investigation, aggressive prosecutors who cut corners and ignored glaring holes in their theory of the crime, and woefully inadequate defense lawyering that left much of the state’s story unchallenged.

The weakness of the state’s case against Glossip has been well known to the courts for years. Glossip’s original conviction was overturned in 2001 when the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals found that his attorneys had failed to adequately represent him at trial. After a second jury found him guilty in 2004, a federal judge noted that the evidence against Glossip was “not overwhelming” but upheld his conviction anyway.

As Glossip’s fourth execution date approached this summer, his legal team asked the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals to grant them the opportunity to present new evidence that had never been heard in court. This week, Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt ordered a 60-day stay of execution to allow the court to consider their request.

“There are a lot of things right now that are eating at me,” Sneed wrote. Things he needed “to clean up.”

In the meantime, new evidence continues to emerge that bolsters Glossip’s innocence claim. In the past two weeks alone, handwritten letters from Sneed have revealed how close he came to taking back his story about Glossip. In 2003, a year before Glossip’s retrial, Sneed wrote to his public defender, asking, “Do I have the choice of re-canting my testimony at any time during my life, or anything like that.” In 2007, he sent the lawyer another letter: “There are a lot of things right now that are eating at me,” he wrote. Things he needed “to clean up.” Although he didn’t specifically mention recanting, he suggested that he’d made a “mistake.” The lawyer, Gina Walker, who has since died, discouraged him from coming forward.

There has never been any dispute over who actually killed Van Treese. In the early hours of January 7, 1997, Sneed carried a baseball bat and a set of master keys to Room 102, where he attacked the 54-year-old motel owner. Van Treese fought back, Sneed later said, knocking him into a window, which shattered. But Sneed eventually overpowered Van Treese, bludgeoning him to death. Sneed then moved Van Treese’s car to the parking lot of a nearby credit union, taking a stack of cash from under the driver’s seat. Sneed hid his bloody clothes and played dumb the following morning when Van Treese’s family called to say that he hadn’t made it home to Lawton, some 90 miles away. It wasn’t until 10 p.m. that night that Van Treese’s beaten body was discovered inside Room 102 amid a pile of blankets next to the bed. By that time, Sneed had fled the motel.

Oklahoma City Police Detectives Bob Bemo and William Cook headed up the investigation, which was cursory at best. The investigators failed to do even the most basic work, like talking to the numerous people who were staying at the motel at the time of the crime. Instead, they quickly latched on to a half-baked theory that has animated the case for nearly two decades: that Glossip coerced Sneed into murdering Van Treese in order to steal his money and take over the motel.

The cops became suspicious of Glossip in part because he’d failed to give them information that tied Sneed to the murder. The night Van Treese was killed, Glossip said, he was startled awake around 4 a.m. by Sneed knocking on the wall of his apartment, which was adjacent to the motel’s office. Sneed stood outside with a black eye and told him that he’d run off some drunks who had broken a window while fighting in one of the motel rooms. As Sneed was walking away, Glossip said he asked him about his eye and Sneed flippantly responded that he’d killed Van Treese. It wasn’t until the next morning, when no one could find Van Treese, that he realized Sneed might have been serious. Still, he didn’t tell the cops right away — he said his girlfriend had suggested that he wait until they figured out what was happening.

Photo: Joseph Rushmore for The Intercept

The most glaring problem with the state’s narrative was the lack of any reliable evidence linking Glossip to the murder. The case against him was based almost solely on Sneed’s claim that Glossip had manipulated him into murdering their boss. The reasons to doubt Sneed’s account go beyond the obvious incentive for him to lie in order to escape the harshest punishment. Sneed’s confession was the result of a highly coercive interview led by Bemo, who all but convinced Sneed to blame Glossip. The detective repeatedly named Glossip as a possible conspirator — and even mastermind — before asking Sneed for his version of events.

“Everybody is saying you’re the one that did this, and you did it by yourself, and I don’t believe that,” Bemo told Sneed. “You know Rich is under arrest, don’t you?” No, Sneed said. “So he’s the one,” Bemo replied. “He’s putting it on you the worst.”

Coercion by the detectives who interviewed Sneed would have been crucial exculpatory evidence for Glossip. Yet the videotaped interrogation was never shown to the jurors who sent Glossip to death row. Over the course of two separate trials, lawyers for Glossip failed to use the videotape to show how Sneed’s claims against their client had been concocted with the help of police.

It was only while Glossip faced his second and third execution dates in September 2015 that his case began to attract wider press scrutiny. Up until that point, Glossip had been primarily known as the named plaintiff in a challenge to Oklahoma’s lethal injection protocol, which had reached the U.S. Supreme Court earlier that year. After the justices ruled in Oklahoma’s favor, giving the green light to execute Glossip, The Intercept published its first investigation into the case, followed by a wave of additional coverage. Soon thereafter, new witnesses began to come forward with information casting further doubt on Glossip’s guilt. Two men who had spent time with Sneed in jail separately contacted Glossip’s attorneys to say that Sneed had boasted about killing Van Treese and letting Glossip take the blame. Rather than investigate these claims, Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater took dramatic measures to silence these witnesses.

Richard Glossip gives an interview from Death Row in the 2017 documentary “Killing Richard Glossip.”

Still: Courtesy of Joe Berlinger; Photo: Elise Swain/The Intercept

Glossip came perilously close to execution in the fall of 2015, spared only by the state’s incompetence in securing the right lethal injection drugs. After it was revealed that Oklahoma had previously carried out an execution using the same erroneous drug it was poised to administer to Glossip, the state’s death penalty ground to a halt. Executions remained on hold for six years.

In the meantime, Glossip’s case continued to attract attention from activists, politicians, and the media. In 2017, documentarian Joe Berlinger released the four-part series “Killing Richard Glossip” — the series that caught Garcia’s attention. Among the major revelations in the documentary was an alternate scenario of the crime. According to a man who spent time with Sneed at the Oklahoma County Jail, Sneed said that he and a woman had lured Van Treese into Room 102 in order to rob him. In other words, this was a robbery gone bad, not a murder for hire.

Glossip’s case also caught the attention of a bipartisan group of Oklahoma lawmakers, many of them rock-ribbed pro-death penalty conservatives, who became concerned that the state planned to kill an innocent man. In May 2021, 34 Oklahoma state legislators, the majority of them Republicans, asked Stitt as well as the state’s Pardon and Parole Board to investigate Glossip’s case. When Stitt and the board failed to act, the lawmakers sought out the law firm Reed Smith LLP, asking for an independent investigation into the case. The firm took on the work pro bono; over the course of four months, 30 attorneys, three investigators, and two paralegals reviewed over 12,000 documents and interviewed more than 36 witnesses. The resulting 343-page report, released in June 2022, contains bombshell revelations that paint the clearest picture to date of Glossip’s wrongful conviction.

“Fundamental concerns and new information revealed by this investigation cast grave doubt as to the integrity of Glossip’s murder conviction and death sentence,” it reads. “The 2004 trial cannot be relied on to support a murder-for-hire conviction. Nor can it provide a basis for the government to take the life of Richard E. Glossip.”

Photo: Joseph Rushmore for The Intercept

A Grave Error

Much of the report focuses on the shocking investigative failures of the Oklahoma City Police Department in 1997. Among the dozens of people interviewed by Reed Smith’s investigative team were employees or guests staying in one of the 19 rooms occupied at the Best Budget Inn the night of the murder. “The police should have canvassed all of the rooms in the motel to determine if there were any additional witnesses to what occurred,” the report’s authors write. Instead, the cops interviewed just four such people.

Detectives never interviewed Sneed’s roommate, the Reed Smith team found. Nor did they interview a motel housekeeper who said that she overheard Sneed telling someone on the phone that Van Treese was “going to get what he deserved,” nor a woman who reportedly heard glass breaking from outside the motel at the time of the crime.

But the report’s most stunning revelations cut to the heart of the state’s case against Glossip. New details about Van Treese’s finances and the motel’s inner workings undermine the state’s theory of the crime and debunk Glossip’s alleged motive for wanting Van Treese dead.

Underpinning the theory that Glossip compelled Sneed to kill Van Treese in return for half the cash stashed under the motel owner’s car seat was the contention that Glossip’s job was on the ropes. According to the state, Van Treese was upset to discover that Glossip had been embezzling funds from the Best Budget Inn — allegedly totaling about $6,100 in 1996 — and had traveled to Oklahoma City on January 6, 1997, to fire Glossip.

The embezzlement theory appears to have originated with Van Treese’s wife, Donna. At Glossip’s first trial, she testified that the family had returned home from a vacation on January 5, 1997, at which time she prepared a year-end report and discovered a $6,100 shortage for 1996. But oddly, there is no mention of any of this in the police reports — not the shortage calculation or the fact that her husband was planning to fire Glossip as a result. In fact, there is no indication that police ever formally interviewed Donna Van Treese. “The lack of any reporting of this from Ms. Van Treese to the police casts suspicion on the state’s motive theory,” the report reads.

“This ‘embezzlement’ theory should not have been presented to the jury. The prosecution should not have presented a theory it could not verify.”

There have always been fundamental problems with the embezzlement narrative, including that Barry Van Treese consistently paid Glossip a bonus for bringing in more revenue per month than had been forecast, which doesn’t square with the notion that any revenue was missing. The Reed Smith report lays out a wealth of additional evidence that there was no verifiable shortage to begin with and that the state peddled this narrative without confirming it. “This ‘embezzlement’ theory should not have been presented to the jury. The prosecution should not have presented a theory it could not verify, and the defense completely fell down in failing to object,” the Reed Smith team wrote. “The jury was told Glossip was stealing from the motel and was going to be fired for it, even though we have found no credible evidence that any of this was, in fact, true.”

At issue was the way in which the Van Treeses handled their motel finances, which appears to have been driven by deep financial problems that neither the jury nor, apparently, the defense knew about. According to the Reed Smith report, Van Treese was heavily in debt to both state and federal taxing entities, and his two motels — the family had a Best Budget Inn in Tulsa as well as the one in Oklahoma City — were mortgaged to the hilt. His accountant, who was never interviewed by police, told the Reed Smith team that the IRS had levied Van Treese’s bank accounts.

Because of the financial problems, which dated back roughly a decade, the Van Treeses had all but abandoned the banking system and were operating almost entirely in cash, much of which was kept in Van Treese’s car. The accountant, Dudley Bowdon, recalled an incident in which Van Treese had paid him for his services from a supply of cash that he kept under his car seat. A receipt for the transaction was recorded on a restaurant napkin.

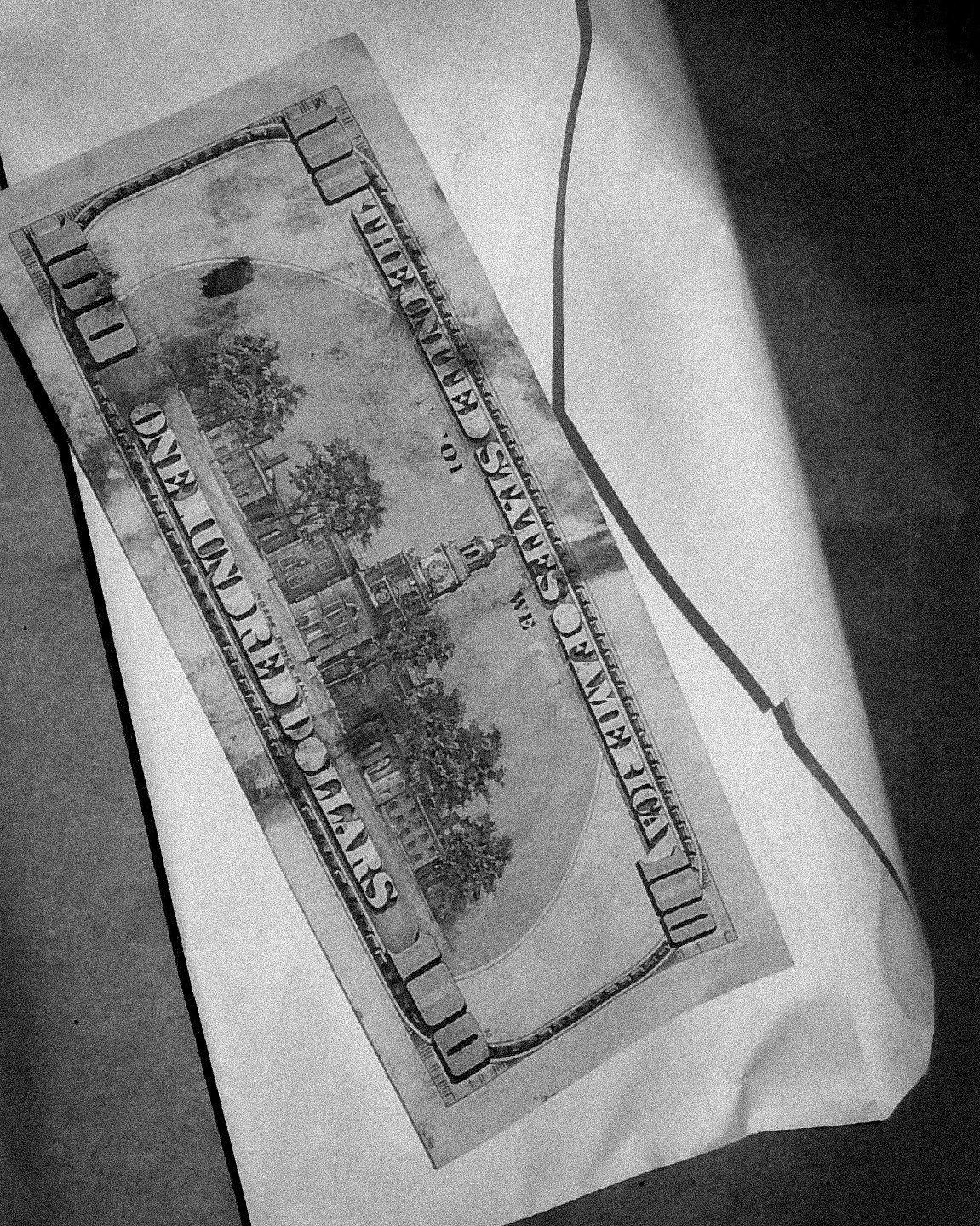

Blood on a $100 bill found in Justin Sneed’s possession after the murder of Barry Van Treese.

Photo: Courtesy of the Oklahoma City Police Department

The state’s core claim that there was a $6,100 shortfall for 1996 — and thus that Glossip had been embezzling money — was calculated by Donna using an improper accounting method, which two forensic accountants say was unreliable and could not be verified. The shortfall was based on Donna’s “business volume” calculations, which were generated by taking an average of the daily room rate — rounded up or down — multiplied by the number of rooms rented. In other words, Donna’s assertion that there was a shortage was based solely on her income projections and not actual revenue. “Over a course of a full year, this could lead to a meaningful discrepancy,” the Reed Smith team wrote. “This methodology of rounding numbers up or down may be an appropriate business forecasting method, but it is not appropriate when attempting to show embezzlement as a motive in a capital murder case.”

What’s more, the team found evidence that Van Treese did not record cash income that was smaller than a $5 bill. As such, Donna’s shortage calculation, “even if accepted,” could be readily explained by Van Treese’s collection habits, the report concluded, “meaning there was no shortage at all.”

Nonetheless, the court allowed Donna’s assertions to stand — even though doing so appears to have violated Oklahoma law, which requires that underlying financial records be admitted into evidence. The majority of those records weren’t available though. Some had been lost in a flooding event at the Van Treese home, Donna testified. And others had been destroyed by the state.

The report also sheds light on astonishing mishandling of evidence in the case. “Police appear to have lost a surveillance video tape showing the night of the murder from the Sinclair Gas Station which was within walking distance from the Best Budget Inn,” it reads. Sneed went to the gas station around the time of the murder; the tape could have provided evidence to support or contradict his story. As the report points out, the surveillance footage could have also revealed whether or not Sneed was by himself.

“The Glossip deal horrifies me. I have no idea how something like this could happen.”

Even worse was the willful destruction of key evidence prior to Glossip’s second trial. Although records show the official reason given by the DA’s office for destroying this evidence was that Glossip’s appeals had been exhausted, this was far from the truth. Retired prosecutor Gary Ackley, who assisted the lead prosecutor at Glossip’s retrial, told investigators that the DA’s office “had a long-standing agreement with the Oklahoma City Police Department to never destroy evidence in a capital murder case.”

Yet Reed Smith interviewed several career Oklahoma City law enforcement officers who described how prosecutors explicitly requested that evidence be destroyed in 1999, in contravention of the office’s own policy. Not only did prosecutors ask police to destroy a box of evidence in Glossip’s case, but the DA’s office also created a new case number “solely for this destruction of this box of evidence,” according to one detective who previously worked in the police crime lab. Ordinarily, the original case number would be used. This conduct was clearly aberrant and unnerving to those interviewed by Reed Smith. One law enforcement officer said it was “not the way it’s supposed to be done.” Ackley was especially blunt. “The Glossip deal horrifies me,” he said. “I have no idea how something like this could happen.”

The box destroyed in 1999 contained 10 items, eight of which Reed Smith identified as being especially important to Glossip’s defense. They included handwritten accounting logbooks that Van Treese kept in his car — a deposit book containing the motel’s financial records and two receipt books containing the motel’s expenses. As the report makes clear, these were “the very financial records … that Glossip would need to definitely disprove there was embezzlement.”

Other destroyed evidence included items recovered from the crime scene that had obvious forensic value, including a shower curtain Sneed used to cover the broken window in Room 102, a roll of duct tape he used to hang the shower curtain, and a wallet that, according to Sneed, had been handled by Glossip yet was never tested for fingerprints. Finally, there were items whose descriptions were vague enough to leave the question of their evidentiary value unanswered, such as an envelope with a note and a “white box with papers.”

It is not clear what these items might have revealed had they been preserved as required. What is clear is that “Glossip did not have any of this evidence for his retrial or any of his post-conviction efforts,” the report emphasizes.

“The state should not be absolved from how grave of an error this is,” the Reed Smith team concluded. “The state’s destruction of evidence is … inexcusable in a capital murder case.”

Photo: Joseph Rushmore for The Intercept

A Significant Threat

And then there is Justin Sneed.

To hear the state tell it, Sneed was simply too clueless to have orchestrated the murder of Van Treese on his own, notwithstanding the savagery of his actions on January 7. But the Reed Smith investigation makes clear not only that Sneed was far savvier than the prosecution made him out to be, but also that the state had evidence of this in its possession long before Glossip was ever tried.

And there were other signs that should have raised red flags — including Sneed’s shifting story about the money Glossip allegedly promised to pay him.

Sneed gave various accounts of how much Glossip offered him for the murder but eventually landed on $4,000, which Glossip allegedly told him would be found under Van Treese’s car seat. Sneed said that he was given around $2,000. When Glossip was arrested on January 9, he had $1,757 on him — proof, as the prosecution would have it, that Sneed’s story made sense. In accepting this at face value, however, the prosecution dismissed key information. First, according to Glossip, his money had come from his paycheck as well as the proceeds from selling several personal items, which he did, he said, in order to hire an attorney to help him deal with the cops. Glossip said that after he was first questioned by police, a friend warned him not to speak to them again without representation; Glossip was ultimately arrested upon exiting the office of an Oklahoma City attorney.

There was no physical evidence linking Glossip’s money to the murder. There was no blood on it, as there was on bills Sneed had in his possession, and there were no similar serial numbers or denominations among the two pots of cash.

And there was an even bigger problem, Reed Smith found, which further discredited Sneed’s story about splitting money with Glossip. Records reflect that the total receipts collected by Van Treese from the motel that week amounted to less than $3,000. One forensic accountant estimated that the amount of cash Van Treese would have collected was actually closer to $2,000, which would account only for the money in Sneed’s possession.

There was no physical evidence linking Glossip’s money to the murder.

Ruling on Glossip’s appeal of his second conviction, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals pointed to the alleged money split as critical evidence backing Sneed’s version of the murder plot. “The most compelling corroborative evidence, in a light most favorable to the state, is the discovery of money in Glossip’s possession,” the court wrote.

The court accepted the notion that were it not for Glossip, Sneed wouldn’t have known about the money in Van Treese’s car. This too was wrong. “He always kept money,” Garcia said of Van Treese. It was common knowledge among the motel regulars, including Sneed, who Garcia said had been agitating to steal from Van Treese for a while — including by trying to get one of her fellow dancers to help out. “I guarantee it,” she said. “It was talked about.” She said she made it clear to her friends that they should not mess with Van Treese; she let them know that “if they had anything to do with that,” they’d “never work another night in any club I was in.”

She said Sneed was constantly in search of money to feed his drug habit and recalled one particularly chilling incident: After complaining about not having money for drugs, Sneed picked up a brick and wandered off. Later, he returned with about $500 and blood on his shirt. Others who were hanging around the motel recalled similar interactions with Sneed. Jamie Spann, who worked at the roofing company with Sneed and shared a room with him at the Best Budget Inn, said in an affidavit that Sneed regularly stole items from other roofers and that he’d seen him steal from one of the houses they were working on. He said that Sneed walked around the motel like he “owned” the place and “wanted everyone to pay him to sell drugs.” He said Sneed wanted those engaging in sex work at the motel to split their profits with him — an allegation that Garcia has also made against Sneed.

None of these behavioral problems were new. Spann had known Sneed since childhood and said he’d been a manipulative “bully type.” Sneed was frequently in trouble for fighting and mouthing off, the Reed Smith team found. In fact, although prosecutors portrayed him as guileless for the jury, Sneed’s troubling history was known to the state prior to Glossip’s first trial. In a competency report provided to the state in 1997, a forensic psychologist found that if Sneed were to be released without “treatment, therapy, or training,” he would “pose a significant threat to the life or safety” of himself or others.

The report, which was completed before Sneed pleaded guilty and agreed to testify against Glossip, also noted that Sneed had a criminal history in Texas — including for burglarizing a house and making a bomb threat against a friend’s school. Sneed explained away each incident by claiming that someone else had forced his hand.

Where the murder of Van Treese is concerned, Sneed has never been able to keep his story straight. His testimony from Glossip’s first trial morphed significantly by the time he testified again in 2004 — roughly a year after he’d asked his lawyer if he could recant — incorporating additional details he’d never told police that were not supported by any evidence. All of this should have raised concern for the state. Instead, prosecutor Connie Smothermon told the jury that such inconsistencies could be explained by the fact that she was simply better at asking questions than her predecessor on the case. “I’m not going to apologize for asking more questions than anybody else did before,” she said, “because, you know, that’s me, I’m a questioner.”

When questioned about the crime in recent years, Sneed has continued to give inconsistent answers. In a 2015 interview with The Frontier, he made the bizarre claim that he had no idea why Glossip would’ve wanted Van Treese dead. The Intercept sent Sneed an email asking about the letters he wrote indicating that he wanted to recant his testimony. He did not respond.

Photo: Joseph Rushmore for The Intercept

A Haunting Experience

Since Glossip last faced execution in 2015, numerous witnesses in addition to Garcia have come forward to share what they knew with his legal team. Their accounts are contained in a flurry of affidavits that consistently portray Sneed as violent and cunning.

“I was shocked to hear that anyone had tried to portray him as someone who is slow, or could be manipulated by anyone, let alone Richard Glossip,” said one man who used to sell drugs at the Best Budget Inn. A roofer who briefly lived with Sneed at an Oklahoma City apartment said that after the murder took place, Sneed returned to the house acting strange. He had a black eye and was “really nervous,” refusing to leave the house and looking out the window a lot. A different roommate eventually saw Sneed on TV and turned him in, according to the affidavit, yet “no one from the defense or the prosecution ever came to talk to me about this.”

Perhaps the most damning accounts come from people who were once incarcerated with Sneed. Among them is Paul Melton, who spent 13 months with him at the Oklahoma County Jail starting in March 1997.

Melton remembers feeling concerned for Sneed at first. “I kind of felt bad for him when I first met him because he was green to prison life, to jail,” he said. “In Oklahoma, that’s very dangerous.” It’s not that Sneed was naïve, exactly. In fact, he was a “hustler” who made money selling cigarettes to his neighbors. But at the same time, “Justin wouldn’t shut his mouth,” Melton said. He would talk openly about his case in a way that was reckless. He remembered telling Sneed, “Everything you’re doing right now is going to follow you to prison, so you better shut your mouth.”

As Melton recalls it, Sneed was clear from the start that he had killed Van Treese on his own. But he also corroborated the account introduced in “Killing Richard Glossip,” in which Sneed and a woman had lured Van Treese to Room 102 as part of a plan to rob him. Melton said this was something Sneed had done a number of times to motel guests. Unlike their previous targets, Van Treese fought back, escalating the confrontation until Sneed killed him. “Justin Sneed and a girl set this up, and it was a robbery went south,” Melton said.

As Melton recalls, Sneed laughed about the fact that Glossip would get the death penalty instead of him.

Garcia also recalled Sneed targeting motel guests this way. “Sneed would use some of the girls who worked at the club to lure men into the rooms so he could set the men up and rob them,” she said in a 2018 affidavit. Both she and Melton described one such woman as Sneed’s girlfriend, but Garcia also said that Van Treese was her “sugar daddy,” giving her gifts and money. Garcia, who worked with the woman, said the police knew about Van Treese’s proclivities but wanted her to keep quiet about it. This is why they never listened to her about Sneed and instead threatened to arrest her if she talked. “If I go saying that Barry was a sugar daddy and I’m running a prostitution ring, I’m going back to prison for a very long time,” Garcia said she was told.

Melton was in jail with Sneed when he cut his deal with the Oklahoma City DA’s office. As he recalls, Sneed laughed about the fact that Glossip would get the death penalty instead of him. “And that’s what stuck with me. He thought it was funny.”

Others who spent time in jail with Sneed were similarly bothered by his boasting about setting up Glossip. At least one tried to tell the state about it long before Glossip went to death row. In May 1997, a letter arrived at the office of then-Oklahoma County DA Robert Macy, from a man who had recently spent time in the county jail. That man, Fred McFadden, had contacted Macy at least once before to share “an experience that truly haunts me.” While in jail, McFadden heard Sneed bragging openly about what he had done to Glossip. At the time, he was sitting at a table along with another man. “He and I were both so disgusted we got up from the table and walked around the pod,” McFadden wrote. “It quite frankly angered both of us.”

In his May 1997 letter, McFadden shared the name of the other man with Macy. But there’s no evidence that the DA followed up on the tip. Instead, prosecutors continued their case against Glossip, sending him to death row the following year.

McFadden died in 2015. Melton did not want to carry what he knew to his grave. When Glossip’s legal team contacted him asking if he’d spent time in the Oklahoma County Jail in 1997, he agreed to speak to them — even though he feared retaliation from Oklahoma authorities. Like Garcia, he feels deep guilt over his failure to share what he knew about Sneed years ago. He broke down in tears during multiple phone calls, expressing anguish and regret that he’d ever met Sneed. “I am not OK with an innocent man being murdered,” he said. “And I know [Glossip] was set up because the murderer told me.”

Discussion about this post